Sex Work

Special Court No. 54 is a hall filled with whizzing ceiling fans. When the magistrate enters or exits, people rise to bow. Lawyers in black coats and white pants or saree/suit, sit at a long desk in plastic chairs a level below the magistrate with a clutch of researchers like myself, and anti-trafficking missionaries who “rescue fallen women”.

Imtiaz Ali’s 5-minute film begins as any trite gangster flick but rapidly flips things around both in narrative and in audience perception.

I’m convinced we’re having the wrong conversation around digital porn. If we really want to have a meaningful conversation around porn, it’s time we stopped talking about its imagined harms. It’s time we started talking about actual harms. It’s time we started talking about the fault lines of consent.

सम्पादकीय नोट : इस लेख का पहला भाग अप्रैल के पहले संस्करण में प्रकाशित हुआ था सेक्स वर्कर के अधिकारों…

Is business work? Can business that involves providing sexual services be understood as work? If work is any mental or physical activity performed for a result, then for the individual performing the activity sex work is work. If work is any activity performed as a means of survival, then sex work is work.

Not only has evolving discourse on sexuality influenced the fate of how sex work is understood, but also with the growth of sex workers’ rights movements, discourses on sex work are now being able to influence how we think about sexuality. In our issues on Sex Work and Sexuality this month, we hope to be able to traverse some of these convergences.

The feminist classic sex work vs prostitution debate was played out in this context in a way that was different from what happens in cis feminist spaces. In the eyes of this narrator, cis feminists who have never engaged in sex work have a lot to learn from travestis and trans women. First of all: the respect.

She was 17 when she was rescued from a dance bar. Now she’s 18 and she wants to go back. As an adult. And dance again. That’s what Alisha wrote in a letter to the Child Welfare Committee.

Alisha’s letter may be one of a kind. It doesn’t matter. It may even be a scam of sorts, in that she was pushed to write it. Doesn’t matter. What’s interesting is the jumble that it throws up, if you look at her choices through eyes that are not hers.

As soon as you add sexuality to a piece about money, the first instinct generally is to reduce it all to sex, leaving the “-uality” like a little invisible tail feather that flutters away into the unknown.

For many of us careening to adulthood at the time, these films pushed us to confront our own biases. They asked us to stand in Diane and Mansi’s shoes and ask ourselves, what would we have done? Would we spend one night with a man (Robert Redford, no less) for a million dollars? Would we be able to resist the option that opened up to Mansi? And the truth of it was that this was a difficult question to answer.

The disruptions in sex work due to demonetisation were not merely about the cash crunch though. Probing deeper, the real problems were to do with a breakdown in the rituals of soliciting, and what it meant behaviourally for the women.

Aspects of sexuality such as aesthetic taste, body image, sexual orientation, desires and aspirations, self-esteem, gender expression, reproductive choices, and more, are all interdependent with the impact of money in our lives and that of those around us. Indeed, our systemic relationship with money has a direct influence on how we ‘value’ ourselves.

Five sex workers – four women and one man – along with the filmmaker/narrator embark on a journey of storytelling….

It was a million dollar question. Literally. The Hollywood film Indecent Proposal (1993) had actors Demi Moore and Woody Harrelson…

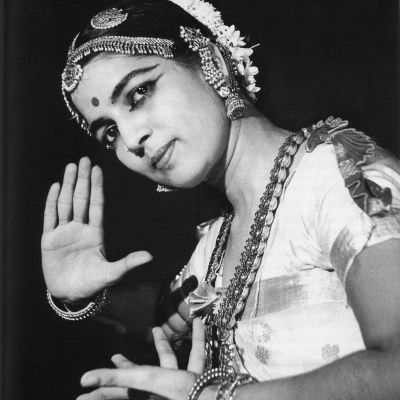

For the two-part interview section of this month’s In Plainspeak, Shikha Aleya spoke to a few individuals who continue to push the boundaries of their work, art, and social norms, and expand the understanding of diversity and sexuality.