migration and sexuality

When rumours of the Partition spread, many families began leaving their homes and moving out. How the Hindus and Sikhs behaved there (in what was to be India), Muslims did the same things here (in what was to be Pakistan). They would say, ‘Let’s go loot!’

Debanuj DasGupta’s current activism and research travels take him through India, UK and the US focusing on issues of national security, migration, and embodied justice. In this (republished) interview, he chats with TARSHI about the issues of queering immigration.

Often, these marriages are performed in great haste as the groom comes to India for a short holiday. In their enthusiasm to clinch, what appears to be a highly desirable marriage alliance, which will open up new opportunities, exposure and happiness to their daughter, the parents may throw caution to the wind and seal the match.

DarkMatter is a trans South Asian performance duo from New York. Watch them perform their spoken word poetry and chat about their trans politics, traversing issues of gender, race, desire, migration and more that connects to it.

The migrant has come to represent threat on many fronts, with sexuality and sexual behaviours storming the front of fronts. This is because sexuality is in itself so threatening to so many; as a word, as a concept, it is untidy, unknown, uncontainable, like that alien substance bubbling out of its pod in the film ‘Prometheus’. Or ‘Alien’.

The nurse looked me up and down and asked about my last period. I responded that it had been recent and regular and that I wasn’t there about a reproductive issue but rather a potential stomach bug. “Mmm hmmm,” she responded, with more than a hint of dubiousness in her voice, and said, “Take this cup, pee into it and bring it back to me. We’ll run a pregnancy test.” I stared back at her. “I’m not pregnant!” She responded, “Well, we’ll see about that. Is that your mum outside? Young girls like you are always coming in like this.”

While Islam was loudly decried a religion of molesters, the European far right – not exactly known for their commitment to gender equality and women’s rights – now appoint themselves the protectors of ‘their’ (i.e. European white) women against an ‘onslaught of Muslim rapists’.

It seems then that there is a direct relationship between the extent of transgression of sexual and gender norms on the one hand, and the need to migrate on the other. Whatever background people come from, migration is almost inevitable and necessary.

“Yo existo. I exist,” asserts Julio Salgado’s self-portrait drawn with wings that give him identity. Salgado was eleven years old when he crossed the border from Mexico to the United States where he remains an undocumented resident. Risking arrest and deportation if detected, Julio makes art about his experiences of being a queer and undocumented person of colour.

The British went to South Asia with their preconceived notions of sexual normalcy stemming from enlightenment and Christian ideals. If anything, it was the British who were the prudes and sexually repressed venturing into India, rather than the sexually liberated souls they claim to be today.

Watch some popular Bollywood music videos about separated lovers across the decades.

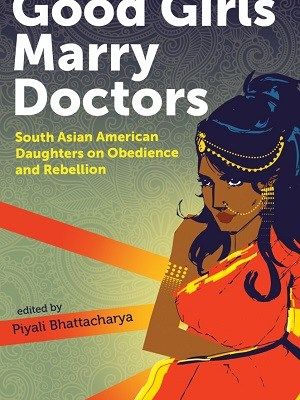

To all the American daughters of South Asian immigrants: Have you ever felt that you just can’t be a Good Girl? Your parents and South Asian community have likely tried drilling in you that Good Girls follow the path of academic excellence, a well-paying job (doctor, lawyer, or engineer), marriage to a well-paid Desi man (preferably a doctor), and then a happy house with kids. Obedience to parents, no dating (at least not while a student), and virginity until marriage are absolutes.

Emmi Kurowski (Brigitte Mira), a widow in her sixties, walks into a bar to take shelter from the rain. She is met with hostile stares by a mixed group of Moroccan immigrants and Germans. As a joke, one of his friends challenges Ali (El Hedi ben Salem m’Barek Mohammed Mustafa), a young strapping Berber man, to ask her for a dance. He agrees, and thus begins a romance across the taboo lines of race and age.

The boisterous figure of Indo-Trinidadian chutney soca musician Denise “Saucy Wow” Belfon has ruffled the feathers of many an Indian-origin immigrant sentiment with her song ‘Looking for an Indian Man’.

यूँ तो विवाह और उससे जुड़े महिलाओं के ‘स्थान परिवर्तन’ को ‘प्रवसन’ का दर्ज़ा दिया ही नहीं जाता है, इसको एक अपरिहार्य व्यवस्था की तरह देखा जाता है जिसमें पत्नी का स्थान पति के साथ ही है, चाहे वो जहाँ भी जाए। पूर्वी एशियाई देशों में, १९८० के दशक के बाद से एक बड़ी संख्या में महिलाओं के विवाह पश्चात् प्रवसन का चलन देखा गया है जिन्हें ‘फॉरेन ब्राइड’ या विदेशी वधु के नाम से जाना जाता है। इन देशों की लिस्ट में भारत के साथ जापान, चीन, ताइवान, सिंगापुर, कोरिया, नेपाल जैसे कई देशों के नाम हैं। यदि विवाह से जुड़े प्रवसन को कुल प्रवसन के आकड़ों के साथ जोड़ा जाए तो शायद ये महिलाओं का सबसे बड़ा प्रवसन होगा।