Voices

TARSHI has been running a survey (we’re still accepting responses) to understand how people feel about their sexual lives during the…

A humanitarian crisis situation has different impacts at the individual and community level and is also differently experienced by different…

When the pressure started to mount on Surekha, from all corners, to get married, she thought of reconsidering Kishore’s proposal…

At first glance, dating and social distancing appear to be oxymorons. But, as the last few weeks have shown us,…

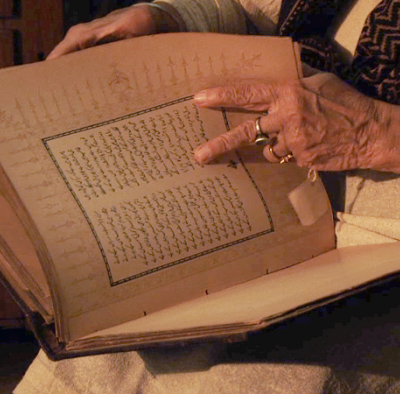

If not him, there is his brother – Mir, are there any restrictions in love? Mir Taqi Mir, 18th century…

A wedding is a major event in a person’s life. The event comes with many dreams, hopes, expectations and desires….

I want it, I got it. Right? Except, what I often get is some approximation of erotic pleasure, which has more to do with my own conditioning about what good sex looks like, and little to do with my body’s erotic mechanisms. This very peculiar condition is often lumped under ‘sexual frustration’, when it should really be addressed under safety.

We all talk of ‘safe’ as some place where we are not in danger. Well, the truth is there is danger everywhere. So, maybe before we even delve into the subject of safety and sexuality, it is imperative that we take a moment to pause and see what safety and sexuality could even mean.

To ensure that important discussions about issues of sexuality can take place at home, in schools and between generations, efforts needs to be made to change the norms – especially those related to perceptions of safety. Individuals, institutions, organisations and policies need to work together to include safe spaces for reflections and opportunities for these discussions to become common practice.

Undoubtedly, LGBTQ+ literature and writing in India has witnessed an ‘explosion’ in the past two decades, and the trends in contemporary publication promise consistent growth in the future too. However, issues of queer representation in existing literature, and especially contemporary literature, need to be continually invested in, for literature is a key marker of society’s outlook on and reception of such sensitive subjects as homosexuality and ‘queer’-ness

Through our discomfort, shame, and often stubborn refusal to rise above heteronormativity, we unpacked a lot of these negative emotions by critically analysing texts that were neither the Kamasutra nor discourses such as Foucault’s on sexuality.

The Handmaid’s Tale leads one to re-examine these two forms of social hierarchy that women have to navigate: one where they apparently have equal sexual rights as men but have to bear most of the brunt of unwanted pregnancies, reproductive burdens and the like, and the other extreme where their decisions including those about sexual identity and procreation are institutionalised and they are robbed of all agency and autonomy.

You held my hand, we hugged each other / I was lost in your love, wanting to go further

Standing behind the camera, with a microphone in one hand, I have felt this power imbalance first hand. The camera may humanise the person in front of it more than a text analysis would, but the modes of production remain in someone else’s hands.

Pleasure, in the context of the private, defines the parlance of sexual satisfaction. As a womxn, the private is also the public: how I present and play with my gender, is a way of seeking validation of who I am.