SISA spaces

No two human bodies are alike, and our different bodies arouse curiosity. But our fascination for the aesthetics of the perfect human body has historically created a space within art, science and religion for the examination of the ‘abnormal’ and the ‘imperfect’. As a result, some bodies are normalised while others become oddities. Freak Shows, and to a large extent, circuses and even exhibits in medical or anthropological museums particularly stand out for dehumanising and objectifying these different anatomies, and oftentimes subjecting these bodies to violence and discrimination.

People we refer to as “digisexuals” are turning to advanced technologies, such as robots, virtual reality (VR) environments and feedback devices known as teledildonics, to take the place of human partners.

Of course, I knew I wasn’t the only person in the world writing about Sherlock Holmes. I, however, thought I was the only one in the world writing about them like that. You know.

Romantically.

Of course, I knew I wasn’t the only person in the world writing about Sherlock Holmes. I, however, thought I was the only one in the world writing about them like that. You know.

Romantically.

The lip colour then enters into a rather queer state of existence as it refuses to stand by the label it is expected to conform to. It moves and escapes categorisation. In its queerness, it renders itself as a paradox. At the heart of paradoxes is the understanding that something is what it is also not. Similarly, the colour of this lipstick is nude, but it is also not. It is possible that it is because of this slippery nature of the paradox that my sexuality as my identity too remains slippery, in motion and fluid.

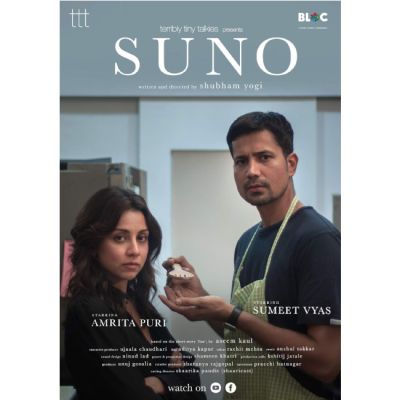

There may be situations in which a person’s responses might not be unquestionably equated with consent. Is consent merely a ‘yes’ or does one need to look for other cues to make sure their partner wants the same thing as them when it comes to intimacy?

Friendship – a place where we can be ourselves as we truly are, with no artifice. A place of peace,…

Vulnerability – is it a condition we find ourselves in? A state of being we choose? Let’s keep it very simple: it depends on the approach we take to defining it. In the former approach, we are ‘done to’, while in the latter we are consciously ‘doing’.

Connection is essential for our survival – physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. We connect with people, form networks of care and support, and in a sense weave webs of safety and comfort that we can turn to when stressed or simply want to infuse a dose of joy into our day.

In this issue of In Plainspeak our contributors reflect on and reveal the myriad facets of being single – is it a choice? A condition? A state of being? Lonely? Joyful? Not one or the other, but a glorious mix?

Continuing with our theme of self-care being about sustaining ourselves, our work, our movements, keeping the fires lit, and relating with love to ourselves, in our mid-month issue we bring you more articles looking at self-care from different perspectives – individual, queer, activist, collective, organisational, not necessarily separated, or in this order, of course.

In our mid-month issue, we add context to our perceptions of and dealings with risk in our day-to-day lives. Collating and interpreting responses we received on a survey taken by small group of random individuals, Shikha Aleya looks at the transactions around risk foregrounded on the interplay of our location on the axes of gender and sexual identity, disability status, belief systems, and availability of support, amongst others.

In our mid-month issue, Stuti Tripathi considers whether raising the minimum age of marriage for women from 18 to 21years is indeed a one-stop solution to check early marriages. She brings to our attention the many factors, such as family pressure, inaccessible educational and financial resources, traditionally defined roles of women, and gender-based marginalisation that together lead to early marriages and argues that young people need rights not protection.

Are certain forms of femininities denigrated more than others? Not just by misogynists but also by feminists? Is there a particular way of manifesting an ‘appropriate’ femininity, one that is just right, and is not ‘too girly’ or ‘too tomboyish’?

Members of a fandom are not just passive consumers but active co-creators who imagine and build new worlds around their objects of adoration. Fandom communities offer fans the freedom of being able to imagine, create and share all sorts of scenarios, including romantic, erotic and sexual ones.