Art

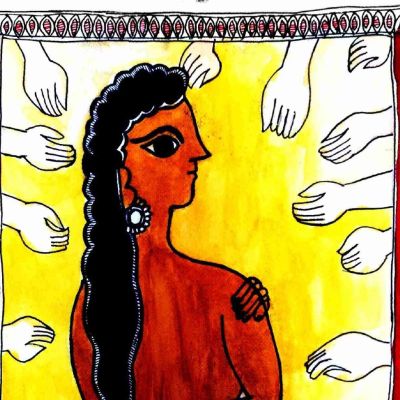

Women’s bodies are considered as symbols of izzat and abru (honour and dignity) making it the woman’s responsibility to ‘protect’ her sexuality, while at the same time, her sexuality is controlled by patriarchs.

This art collection bears the evocative title “Aching Palates”. Within its realm, each artwork embodies an emblematic act that accompanies…

Within its realm, each artwork embodies an emblematic act that accompanies the intricate ritual of food: hunger, gathering, fire, serving, devouring and, ultimately, nourishing.

Body is born, as a collection of many parts, into the various collections of bodies. Different combinations or collections are projected onto various historical, spatial and temporal dimensions, out of our needs, desires and capabilities.

“Something about this pose brought about a sense of owning my body, my persona, my expression, my sensuality, my whole being. The drop of the hip made the bottom vertebrae curve, and appear out of alignment from the rest of my spine. A deviance, defiance of the normal straight stance. A resistance, a revolt of sorts.”

Every part of life, the world too, is storied. Stories are the thread that hold histories and truths together. Stories are at the core of myth-making. Everything that we know is part of multiple crisscrossing relational storylines that we raise and those that we have no power in raising.

In this write up, we’d like to share a sense of what emerges from a compilation of these responses. This is based on the thoughts and feelings that come through for those of us here at In Plainspeak who have had the joy of reading the original responses as they came in to us. (Some of the quotations that follow have been slightly edited for flow and to help connect themes.) We know that most things in the realm of art, information and ideas lend themselves to a wide range of inferences and insights depending on the individuals making the inferences.

Scribbles: an Escape From the Mundane is a product of my thoughts and emotions when I was struggling to understand my sexuality and grappling with the idea of identifying with the spectrum of gender and sexuality outside the binary, but not being able to put a label on it.

Taboos in relation to female desire, sexuality and the body are often addressed in my work. My recent artistic interest focuses on rituals that are primarily centred on agricultural communities in Bengal that involve the veneration of fertility symbols and celebration of feminine sexuality.

Through multiple maquettes, I finally came across (since I myself did not know what the result of the form or figure would be) the Reclining Lady. She represents confident femininity and vulnerability. The feeling one has after taking a bath and sitting in the nude, drying oneself in unabashed nakedness.

I was watching something recently that said it was a bad thing to be vulnerable, but I don’t think it is a bad thing. I do see that there is a certain amount of power in vulnerability, it also needs courage, in my experience.

Most of us, during childhood, internalised the lesson that sex or pleasure is ‘dirty’ and ‘bad’. Artists around the world are increasingly using ‘tactile art’ to challenge the shame and embarrassment that people feel when they look at their bodies.

Here, in Part 2, each interviewee addresses aspects of sexuality and diversity from their own particular space of personal knowledge, as well as work, advocacy, art and activism across diverse fields.

Artist Amanda Oleander’s paintings chronicles the everyday lives of couples and the various mundane things they do together that are simultaneously deeply intimate and poignant.

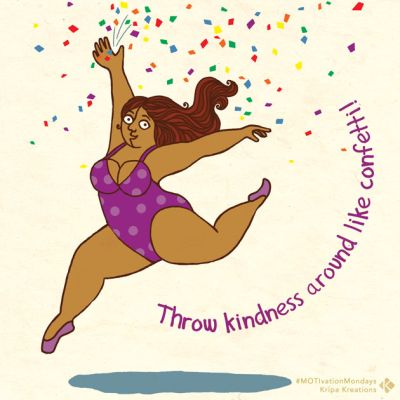

Kripa Joshi, an Illustrator and Comic Artist from Nepal, is the creator of Miss Moti, a character who defies stereotypical notions of how a person should look, feel and be. Kripa’s own experiences growing up as a plump person and her struggles with weight, have informed and inspired Miss Moti.