Being a sex positive parent sounded much easier in theory than it is turning out in practice. I wrote about it on this very forum when my daughter was much younger, though even then I was asking myself all kinds of questions and was by no means convinced I was doing a good job.

When the first lockdown was imposed in March 2020, my daughter was nearly ten and now she is nearly 12. These two years have been interesting with both of us teaching and learning from home, dancing around each other, shifting desks and rooms.

As a result of these overlapping spaces, us listening into each other’s classrooms, our own conversations and her reading and research I now have a ‘woke’ tween. In some ways this is as exciting as it sounds. In other ways I wonder if, without the pandemic, this moment might have been a few years away?

The first time I actively realised that a particular kind of conversation had begun was when I was discussing the instability of not just gender but also sex in an online class. I used the example of the Olympic games and how they could not agree on how to define a woman – to make this point to my students. We discussed Caster Semenya and the multiple times the athlete had to fight to compete as a woman. My daughter happened to be listening. The pandemic meant that she now had an old laptop of ours that she used to access online school. It also meant that her capacity to search for things online grew exponentially. At first she quizzed me and I answered her as best I could. Thanks to online search engines, soon she knew more about Caster Semenya’s career and gender troubles than I did. She found a documentary on Caster Semenya and in turn insisted I, her father, and her grandfather watch it.

Access to online research gave her space and time to read about the gender and sexualities spectrums and soon I was being regaled with the multiple different kinds of identities and the flags that each identity had. Did you know that there are nearly 2 dozen pride flags or that there are specific pansexual and agender pride flags? I didn’t. I was now learning things from her. She also knew what each one looked like and we had to explore online shopping to see if we could find a specific flag pin for her. We didn’t. But we found a lovely pin that read: “Let me be Perfectly Queer” which she loved.

As a generation X-er I grew up in a world that was challenging sexuality but only encountered the instability of gender as an adult in radical new academic texts which were not then yet part of our everyday narratives. My daughter born between Gen Z and Gen Alpha is growing up in a world of gender fluidity and multiple pronouns. “You can refer to me as he, she or they,” she told us one day.

*

Her father and I always read aloud to her. This ranged from him reading out Shakespeare, Premchand and Greek mythology to my reading Arshia Sattar, Eva Ibbotson, Annie Barrows, and Grace Lin even as I discovered a world of children’s literature which had not existed when I was a child.

During the months of the pandemic, my tween also became a reader. The kind who grabs a book as soon as it arrives; scours sites looking for books, and insists that she read you a paragraph from her book right now. The kind of reader who stops in the middle of a sentence laughing, and reads it aloud so we can both laugh together.

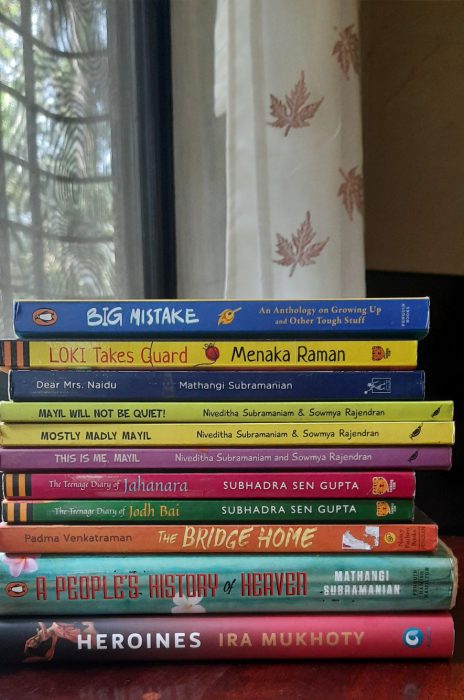

Long before she was old enough to read it, I’d bought a copy of Mayil Will Not Be Quiet! by Sowmya Rajendran and Niveditha Subramaniam. During the pandemic, she began book 1 and very quickly demanded the sequels: books 2 and 3. The books engaged a variety of themes I wanted her to think about and encounter in literary worlds. Periods, sex, flashers, molesting cousins, dating, peer pressure, nasty kids, boyfriends using photographs to blackmail. While reading she would stop and say “Hey, listen to this,” and then we’d talk. She wanted to know if anyone ever blackmailed me. We talked about the guys who flashed me on the local trains. The books also have parents who are allies (and believe their daughters without question, and slap molesting cousins), even as they struggle with the world of parenting and a hep progressive aunt who threatens blackmailing boys with prison. And yet, I was nervous too, because at some point my daughter came up to me and asked, “What is porn”? Now this was a question I was not quite ready to answer right then. I wondered if I’d made a mistake by buying her book 3 which was slated for an older age group.

She read Mathangi Subramanium’s Dear Mrs Naidu and People’s History of Heaven; Loki Takes Guard by Menaka Raman and Hot Chocolate is Thicker than Blood by Rupa Gulab. These books spawned conversations on the right to education, sexism, siblinghood and friendship. Quite by chance, I found another book by Rupa Gulab called, I Kissed a Frog on an online shopping site, and on impulse bought it. By this point my daughter was reading faster than I could read with her and so I had to rely on book blurbs. One day she asked me, “Did you read this book?”. “No”, I said. “I thought not”, she said. “It has sex and people having relationships with married men”. I almost swallowed my tongue convinced I was a terrible mother to have bought such a book for my child.

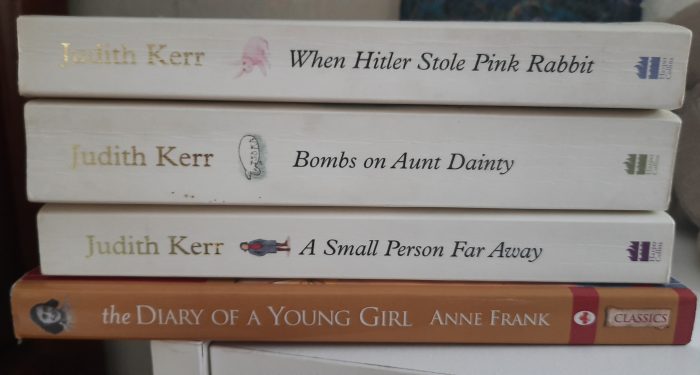

As part of a book club she was introduced to holocaust literature and read the stunning When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit by Judith Kerr and then demanded the two sequels. I was on reader parent heaven. She then read The Diary of Anne Frank. What I didn’t anticipate was that she’d go straight to the search engines researching children in concentration camps. The Internet had a lot to answer for.

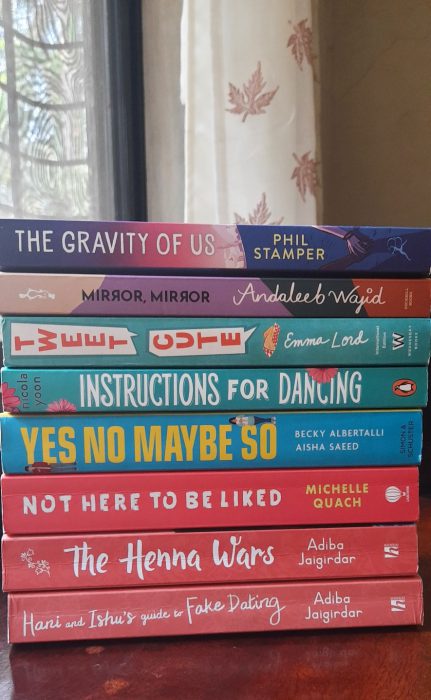

At some point as her classmates became possibly romantically interesting, she also wanted to read romance. As a lifelong connoisseur of the romance genre this fazed me not even a little bit. I was introduced to Georgette Heyer by my grandmother and am among that part of the audience who had read Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton series long before Shondaland made them famous. While I was very comfortable with her reading about consensual sex and sexuality I was more than a bit nervous about anything that suggested sexual violence, or really anything I thought would be difficult for her to engage with.

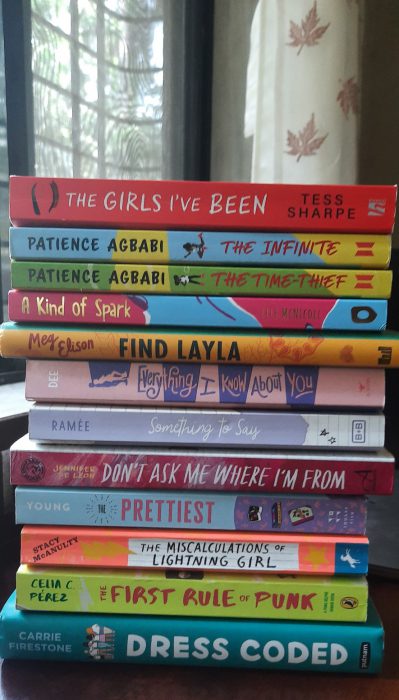

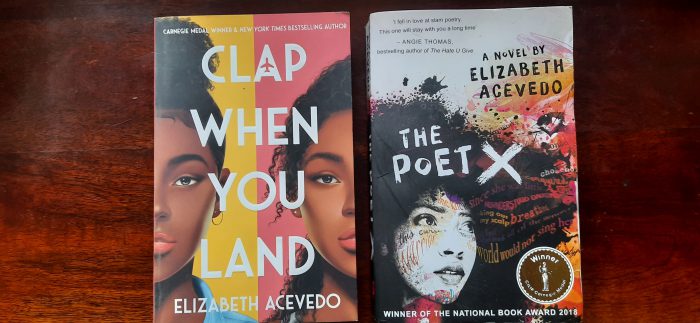

So when she asked for Barbara Dee’s Everything I Know About You, a book that had an anorexic teen in it, I balked. “Do you think reading about an eating disorder is going to give me an eating disorder?” asked my now 11-year-old raging. Sometimes, I’d find a book, read the blurb and send it to her, only to read reviews afterwards that mentioned sexual violence or child sexual abuse. Tess Sharpe’s The Girls I’ve Been was one of them. When it arrived, I decided I would read it first, concerned that I might decide it was “not suitable”. My daughter decided this was not to her liking and I found her reading it at the same time, picking it up as soon as I put it down. The book was riveting. Both of us raced through it with her finishing before me. It was rather dark. But stunning. Another duo of books, I chose myself, but later had doubts about the age appropriateness of, were Elizabeth Acevedo’s Clap When You Land and Poet X. Both are coming of age narratives, written in verse, that explore complex themes of adultery, puberty, sexuality and also the threat of sexual violence. However, both of us read the books. I managed to read Clap When You Land, before her and gave her a sense of the themes that might not be easy for her. Poet X, she read before me and kept urging me to read until I did.

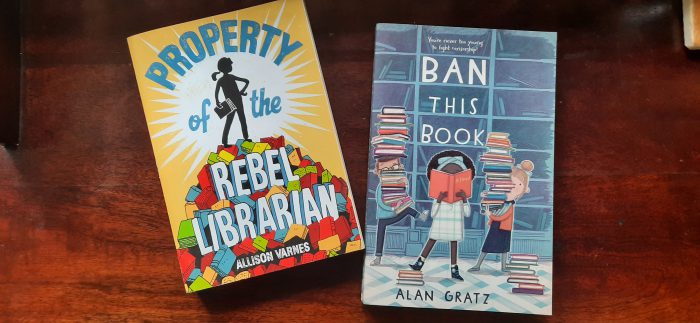

At some point, in my ‘wisdom’, I had introduced her to the complex world of censorship and bought books that talked about the censorship of books. She duly loved Ban this Book by Alan Gratz and read Property of the Rebel Librarian by Allison Varnes. Choosing these books was like providing ammunition to my 11-year-old whose current ambition it is to be a lawyer. She practices her not inconsiderable her skills on me. These skills include shaming: “Are you censoring my books now?” she asked. These skills include rhetoric: “You wanted me to be a reader didn’t you. Now I’m a reader and you don’t want me to read”. These skills include reason: “You think I can’t handle these themes because you think you would not have handled them at my age, but I am not you.” These skills include threats: “I will expose you. I will write that you are censoring my books. The Shilpa Phadke of Why Loiter censors books – you will be cancelled”. Clearly she is destined to be a lawyer. I am in turn in awe of and exasperated by her capacity to argue until I am holding my hands over my ears begging for mercy.

*

I’ve always seen myself as a liberal parent. One who is open to the fact that my daughter is growing up in a world quite different from the one I grew up in. We have open-ended conversations on sex and sexuality. And as the foregoing piece makes clear we have lots of battles too. As a parent I never stop second-guessing myself. I want her to be able to read what she wants. But I worry that it might be too much for her to deal with. I remember myself at eleven. But I was eleven in the 1980s. I don’t want to censor books, but at the same time I feel like I might be a bad parent if I don’t at all think about the possible impact of some texts. I don’t want to censor, but…

The questions are unending. But I am deeply grateful for the range of books that help us navigate the unending questions and for our multi-layered conversations, always a source of joy and reassurance. This by itself is no little cause for celebration.

Photo Credits: All images courtesy of author