Art

In this write up, we’d like to share a sense of what emerges from a compilation of these responses. This is based on the thoughts and feelings that come through for those of us here at In Plainspeak who have had the joy of reading the original responses as they came in to us. (Some of the quotations that follow have been slightly edited for flow and to help connect themes.) We know that most things in the realm of art, information and ideas lend themselves to a wide range of inferences and insights depending on the individuals making the inferences.

Every part of life, the world too, is storied. Stories are the thread that hold histories and truths together. Stories are at the core of myth-making. Everything that we know is part of multiple crisscrossing relational storylines that we raise and those that we have no power in raising.

“Something about this pose brought about a sense of owning my body, my persona, my expression, my sensuality, my whole being. The drop of the hip made the bottom vertebrae curve, and appear out of alignment from the rest of my spine. A deviance, defiance of the normal straight stance. A resistance, a revolt of sorts.”

Body is born, as a collection of many parts, into the various collections of bodies. Different combinations or collections are projected onto various historical, spatial and temporal dimensions, out of our needs, desires and capabilities.

Within its realm, each artwork embodies an emblematic act that accompanies the intricate ritual of food: hunger, gathering, fire, serving, devouring and, ultimately, nourishing.

This art collection bears the evocative title “Aching Palates”. Within its realm, each artwork embodies an emblematic act that accompanies…

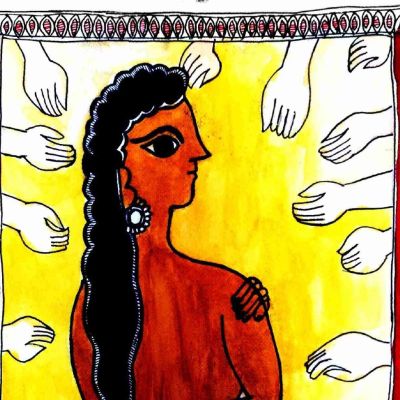

Women’s bodies are considered as symbols of izzat and abru (honour and dignity) making it the woman’s responsibility to ‘protect’ her sexuality, while at the same time, her sexuality is controlled by patriarchs.