Nagarkirtan, the 2017 Indian Bengali film is a must-watch for everyone who hasn’t been able to find a space to socially locate and proclaim their desires. This inability relates to the majority of Indians who have been compelled to live a lie all their lives because they cannot amalgamate their sexual identities and desires with social expectations. This concern appears to be a private affair, but the public is panoptically present everywhere to limit privacy in India. Nagarkirtan, written and directed by Kaushik Ganguly, features Riddhi Sen who is born Parimal but later begins to live as Puti, a transwoman in West Bengal, and Ritwick Chakraborty as Madhu, a flute player from the kirtaniya (kirtaniya refers to devotional music) town of Nabadwip, also in West Bengal. The movie bagged the Special Jury Award (feature film) and the award for the Best Actor at the 65th National Film Awards.

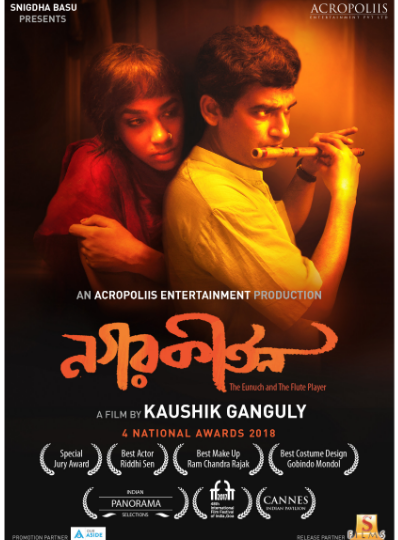

In the poster of the movie, we see the protagonist Puti leaning on her lover Madhu’s shoulder who is engrossed in playing the flute. It immediately hints at the kirtaniya overtone of the movie; whether the duo defines the new-age Radha-Krishna remains a mystery that is concealed until the climax. While the field of sexuality is finally gaining some momentum as far as the liberty to talk about non-heteronormative sexuality is concerned, it still needs to gain further movement in order to redefine a space for itself. The movie begins with us finding Puti, among a group of hijras, gradually falling in love with Madhu and imagining a life different to the one she is living at the moment. As the plot beautifully unfolds, there is a constant contestation between Puti’s past as Parimal and a probable future; between her being dejected in love because of not succumbing to the standards of being either ‘woman-like’ or ‘man-like’ in the absolute sense of each. Through various instances, we glance through the paraphernalia of Puti and Madhav, and how, when they travel across space, these objects, which are not reduced to being just a handbag, a flute, Puti’s bra, or wig, seem to translocate too. The plot of the movie narrates the tale of the love that grows between two people who are struggling to survive in a world of rootlessness and are continuing to make a cosy home for themselves. The love between Madhu, who works as a food delivery boy, and Puti, who survives by singing at traffic signals, blossoms while they cross paths everyday at the traffic signal and the look that they exchange appears to us as if each of them is trying to find a home in the other. The seamless acting and characterisation of both Ritwick and Riddhi make it immensely easy for us to believe Puti to be a woman from the beginning. The poise, the movement and the grace with which Riddhi manifests Puti amazed me. Ritwick’s greatest achievement remains to realistically approach Madhu’s character − a suburban man who wants to give his Puti a new identity, a new body, but is sometimes confused regarding his own sexual preferences. This idea becomes all the more relevant when he asks Puti, “Erom hoye? Eyi chhele chhele te bhaalobaasha?” (Do you think this can really happen − this love between one boy and another boy?)

The lovemaking scene that occurs between Puti and Madhu is not just sensual but recreates the meaning of mutual embrace for me. For a moment, when I see Puti emerging from all her cocoons and experiencing pleasure uninhibitedly, I feel as if a thin trickle of water were running down my body…because that’s the beauty of that moment. The coming together of not just two bodies but two identities and two individuals, grasps my attention and doesn’t appear incongruous to me at any particular moment. What is the beauty of lovemaking if we haven’t been able to get out of our cocoons and embrace the person before us? Puti is courageous, she does it outrageously, but most of us continue to carry our cocoons to the grave. And what do we miss out on? We miss out on experiencing the immense strength of desire, desire served to us in a glass cup like freshly brewed wine. When I see Puti moving on the bed, her body vibrating with the touch that she feels, I can smell the freshness of the intoxication of desire. That dishevelled cot becomes a winery that never ceases to churn desire and pour it for me right before my eyes!

Beyond this ethereal saga of romance, the movie serves as an eye-opener for those of us who haven’t even thought once before ignoring the transgender people who knock on our window screens amidst the traffic signals. These individuals are first excommunicated from our living spaces and then condemned for building a space for themselves. The fact that director Kaushik Ganguly chose to make a transgender character his protagonist is an attempt to create a space for such plots in Indian Cinema. He also deserves a round of applause for setting an apt example of how lovemaking should be projected in Indian movies. It’s time to remove the trembling flowers and showcase the real bodies that tremble in ecstasy and pleasure. The film moves through the constant attempts being made by the couple to gather money and information about gender-alignment procedures and simultaneously portrays the pessimism, contempt and discrimination that they have to face for attempting to find a little space for themselves in this cruel world. Puti and Madhu’s relentless struggle goes in vain as they are tortured and judged for attempting to break out of the margins that society has pushed them to. They are just not allowed to exercise their control over their sexual desires as that dictum is set by society and even if they try, they cannot continue to live as their unadulterated selves in their society.

Puti, even after being thrust to the ground, even after being discarded as an individual, comes before me as fresh, as refreshing, as a newly blossomed rose. Puti desires to be a woman, desires to have not only the body but also the heart and soul of a woman. She has been rejected in love, exploited and turned to the corner because she can never be accepted in society − both of her own and that of the man who she falls in love with. In self-pity, she cries before the mirror and makes me remember moments from my own life where I have done that myself because I haven’t been accepted for who I am, where I come from, what religion I follow, or what food I eat. Amidst all the cynicism that the movie showcases, what makes me feel positive is to watch Puti continuing to imagine herself as possessing the contours of feminine beauty. However, sometimes even after being hopeful about a better future, there is a feeling of not belonging, of being uprooted, that prevails within Puti. This rootlessness is made alive towards the end of the film where she submits and accepts defeat before society. Puti’s submission is a symbol of the incessant rootlessness that the transgender community suffers in a society obsessed with the gender binary.

The movie is a journey of discovering one’s sexual space, of being able to locate one’s seat of desire − both for Madhu and Puti − of being able to feel the strength of desire and see whether it can stand the test of tumultuous times. In a country like our own, where one’s sexuality is strictly defined according to the norms of society, Puti and Madhu constantly inspire us to become like them − to hold the courage to at least attempt to walk on the path of Desire. The final scene where Madhu joins the group of hijras blurs the boundaries of gender for us. It appears as if the young man wants to shriek and tell us that the body is nothing without desire; it is an insignificant heap of bones moving around and having an aimless existence if unable to feel desire.

Nagarkirtan is definitely not a movie which one can forget about and continue with life’s humdrum affairs once back home. It is a movie to get back to, even years later. It episodically narrates a tale of a heartbreak − one which is inflicted by the society that Puti lives in. Puti’s failure at the end is not hers but ours; of our thoughts, our emotions and our false identities as educated individuals and society as a whole. We sit there like unseeing puppets as the world around us burns with millions of individuals like Puti being forced to accept defeat, and we feel we are safe as we have pulled up the glass windows of our air-conditioned cars.

Cover Image: IMDb