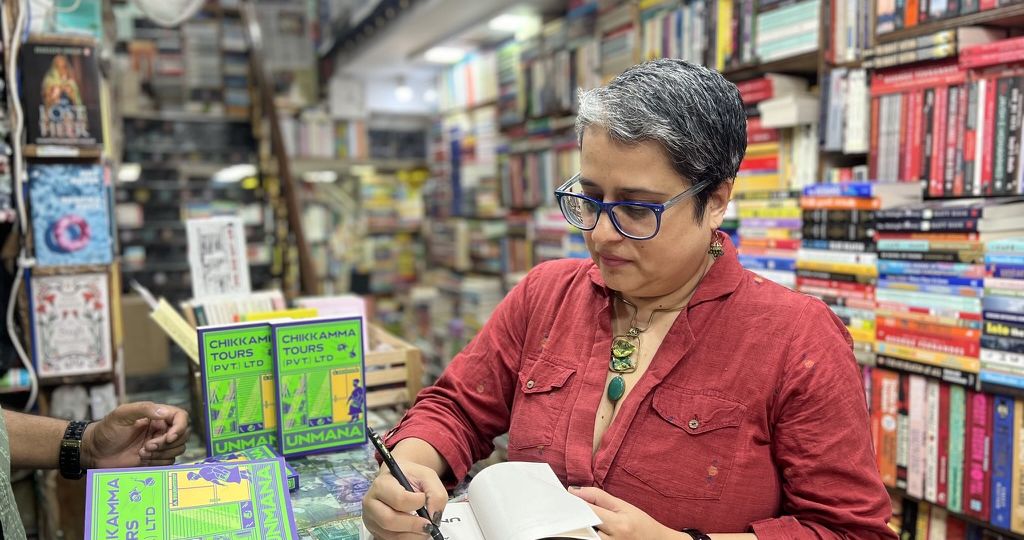

Unmana is a writer who lives in Mumbai. Their short stories have been nominated for the Best of the Net and the Deodar Prize. Their first full-length novel, Chikkamma Tours (Pvt.) Ltd, a murder mystery set in Bengaluru, features India’s first fictional queer detective. Described by Storizen as “Packed with sharp wit, warm charm, and a healthy dose of queer chaos, Unmana’s debut is a cozy mystery with teeth—and plenty of heart.”

Shikha Aleya (SA): We are so happy to interview you on the theme of Friendship and Sexuality, thank you Unmana! Around this time last year, three of your poems were published in an issue of In Plainspeak. In this one titled, “I dreamt I was gliding through a large resort with my best friend”, you write, “She was a member but I felt wrong…” So a quick first question. How important really are feelings and friendships, in the lives we lead, where we are taught about squares and circles even as we learn to walk and are assessed by our ability to fit things into pre-determined shapes as a measure of who we are?

Unmana (U): If you’d permit me to edit your metaphor, I’d say we’re placed in those squares and circles as soon as we’re born. Very few of us actually fit in them: not our bodies, not our feelings.

“I dreamt I was gliding through a large resort with my best friend” is a transcript of a dream about belonging and unbelonging. That line you’ve quoted, “She was a member but I felt wrong…”, implies this duality. The friend is a member of the club, literally; the speaker is not, but is there with the friend: a tenuous, distanced belonging. The speaker is out of place, and then they meet a young child who also seems out of place, but seems unconscious of it.

Relationships and feelings are at the core of my work. My newsletter is called Emomail. My book centres friendships between women. While writing Chikkamma Tours (Pvt.) Ltd, the core of the story to me had always been the friendships Nilima – the main character, a lesbian who investigates a murder – makes with other women (queer, trans, and of unspecified sexuality), especially her relationships with the two other women at Chikkamma Tours, Shwetha and Poorna.

SA: Many people will find great resonance with your questioning in this post, why simply wanting, without reasons “that we can defend, that aren’t emotional” is so often considered suspect. You end by asking readers two questions: “So tell me, friend, what are you doing these days because you want to? What do you want to do but haven’t started?” Why do you offer this word, ‘friend’, as you reach out to strangers, about something at the heart of constructing self and identity?

U: My newsletter has a very small audience. I know most of the people who are signed up, and even if I don’t, I assume they know me. ‘Friend’, therefore, is used more or less literally.

But I use ‘friend’ to address people in other contexts as well: partly because it’s gender neutral, partly because it signals my intent. If you’re listening to me, if you’re giving me the gift of your attention, I appreciate that; I want what’s good for you.

SA: Thank you! Now this question is about the writing process behind Chikkamma Tours (Pvt.) Ltd. You have said, “At the time, I remember thinking I wanted characters who I hadn’t seen in fiction but who felt real to me, who acted and talked and looked like me and my friends.” Please give us a little glimpse into the universe of Unmana and friends. What is it about these relationships that have become an integral part of you and your writing?

U: When I started writing Chikkamma, I had – I still have – encountered very few queer women characters in Indian fiction. Not merely as protagonists: queer women didn’t exist on the page at all. I was writing partly in response to that. I see so many queer women and gender non-conforming people and non-binary people in real life: I felt my novel needed to include, to centre, such characters.

And this representation has been embraced by readers, especially young queer women, who’ve told me how the book mirrors their experiences and their relationships.

SA: A last question! There are people who tend to approach friendship in the way of a last-minute extra seat at the table. What’s missing? How do we do justice to this relationship, and to ourselves, beyond the Happy Friendship Day memes and messages?

U: I agree friendships are often deprioritised, in real life as well as in literature. In Chikkamma Tours, I wrote Nilima’s friendship with Poorna as a parallel, if contrasting, relationship to her friendship with Shwetha: one starts off with dislike and the other with a heady crush, but in both Nilima slowly learns to know and trust them. This is circular reasoning, but we prioritise friendships by prioritising them. Nilima and Shwetha and Poorna look out for each other in ways small and big, whether it’s taking the injured party to the hospital or rescuing your friends from a murderer or holding out an arm in case your friend loses her balance while she’s sitting on the terrace parapet.

For people who feel unaccepted by their families of origin, like Nilima, friendship is a way to build new families. Nilima’s best friend Preeti has become her family, and now that they’re in different cities, Nilima is profoundly lonely. Friendship for her is therefore a higher priority than it might be for the other characters: Shwetha has a large network of relatives and friends and acquaintances to fall back on; Poorna has her close-knit family to go home to; Nilima’s ex-girlfriend Hafeeza and Inspector Sharmila Lamani have each other (they are in a domestic partnership). But Nilima has no one but friends to turn to for help when she is in trouble.

Friendship for me is the ultimate form of relationship, not just in itself, but in its underlying presence in all kinds of relationships. No relationship – familial, professional, romantic –works well without the mutual liking and trust that is essential to friendship.

Cover Image: Shivani Kaul