Activism

The most satisfying spiritual and sexual experiences I’ve had were not in my twenties, thirties or even forties. They have been in my 50’s. The most insightful spiritual insights, and the most orgasmic orgasms have both arrived in middle age.

मां बनने के बाद से आत्म-देखभाल पर मेरे नज़रिये में बहुत बदलाव आया है। एक अभिभावक की भूमिका निभाते हुए और उसकी चुनौतियों का सामना करते हुए अपना ख़्याल कैसे रखा जा सकता है?

हमारा मानसिक स्वास्थ्य सिर्फ़ हमारी इकलौती ज़िम्मेदारी नहीं है बल्कि उन संस्थाओं और व्यवस्थाओं की भी ज़िम्मेदारी है जिनका हम हिस्सा हैं। इसलिए हमारी सेहत और ख़ुशहाली बनाए रखने के लिए इनका योगदान ज़रूरी है।

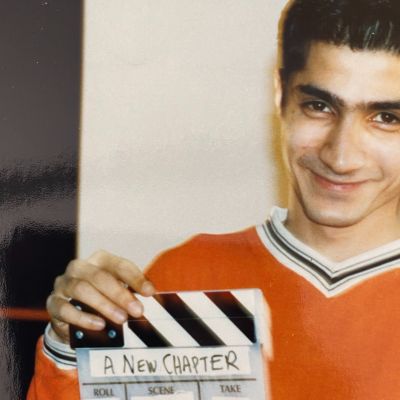

While Nishit Saran’s iconoclasm loomed large in his lifetime, his oeuvre as a pioneering queer filmmaker and activist seems to have been largely obliterated.

But self-care is not a clean and happy procedure, it is not definitively achievable when systematically explored. To understand the scope of self-care we need to see the ‘dark side’ of the landscape, and destroy the versions of self-care that denounce our plurality. In this fight, the only outcome can be a recognition of experiences beyond the wellness narrative structured around the neoliberal agenda. This article is an attempt at foregrounding some aspects of self-care that decentralise the prevalent commodification of it.

Digital entanglements transcend bodies, time, geographical borders and boundaries, influencing – and perhaps fundamentally changing – the ways in which we understand, explore and express our sexuality.

Queer Intentions manages to capture the vast nuances of the queer experience, as Abraham creates space for LGBTQ+ people of a whole spectrum of identities and diverse walks of life to tell their stories.

Our bodies are the vessels through which we feel, emote, work or navigate our societies and the world at large. Our bodies are the real, live archive of everything we have experienced and they have borne the consequences of our social conditioning and decisions.

The linkages between access, health, violence, the law, workplaces, gender and sexuality are really high and that’s why we all today—whether we are working on street accessibility, education, disability and employment—need to bring and build our collective understanding around gender and sexuality, keeping it at the core of our work with people, youth, and women with disabilities.

Self-care is influenced by the environment we inhabit, the way we relate to others, the way we negotiate with other living beings or structures. Self-care is also interlinked with other types of care – whether that is in community resources, psychosocial support, engagement with medical and health care institutions, and of course in collective agency and solidarity.

We need to recognise that mental health stressors that queer people face are not because something is inherently wrong with them.

Both sexuality and disability are complex terrains, offering a realm of possibilities that are often made unnecessarily complicated and unattainable by the mental maps we draw of them and the artificial barriers we erect.

Disabled people might not have many spaces where they can speak openly about their sexual experiences or even sexual curiosity. There is a heavy monitoring of disabled young people especially, and this can mean that exploration, which is often how many of us discover sexuality, can be limited. Moreover, since the experiences of disabled people are not seen in popular media such as films, we can (and probably do) imagine we will have the same or similar experiences as non-disabled people – which is often not possible.

I cannot let anyone see the stretch marks, the cellulite, the saggy breasts. I cannot reveal my hideous body. I feel anxiety well up inside me even as I visualise this eventuality. I read about ten ways for a fat person to have meaningful sex. I learn that throwing a cloth over the bedside lamp will help hide my flaws.

What vindicates the argument that women with disabilities (WWDs) should be deprived of sexual and reproductive healthcare and rights is scary. Harmful stereotypes of WWDs include the belief that they are hypersexual, incapable, irrational and lacking control. These narratives are then often used to build other perceptions such as that WWDs are inherently vulnerable and should be ‘protected from sexual attack’.