Half an hour into the bus trip from Chisinau to the village where I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in central Moldova, my seatmate beckoned to the book on my lap and asked if she could have a look.

A friend of my host family, she was a well-educated woman in her early 30s who spoke French and English in addition to Romanian and Russian. I handed her the manual on reproductive health produced in Romania, and she leafed through it intently, nodding as she did so, then asked if she could borrow the manual.

‘No one had sex during the Soviet times,’ she said in a deadpan way, common to a place where sarcasm remains key to coping with the past.

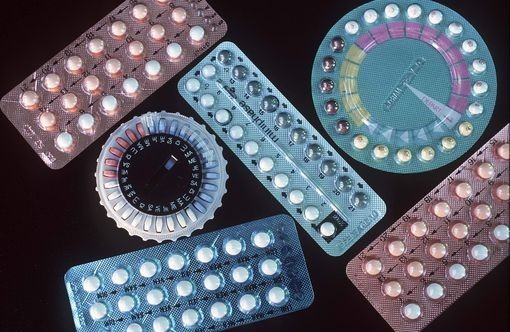

There was, of course, plenty of sex in the former USSR, known for mass production of low-quality oral contraceptives and high rates of abortion. Talking about sex, though, appears to have been far less common, and this persists in the region.

I arrived in Moldova in 2007 to teach health education not long after the government pulled out a long-planned life skills course from the national secondary school curriculum. At the last minute, the Church, a key stakeholder in a 97-percent Eastern Orthodox country, had pushed hard to remove the course, which included topics such as sexuality, HIV and AIDS and the dangers associated with drug use. Reversion to the status quo meant no student in Moldova was educated on sexual health issues in a formal setting, save in communities like mine – a few dozen in total – where a local teacher and a Peace Corps volunteer paired to offer optional health courses. This decision came as HIV in Moldova was shifting from being a disease transmitted primarily through drug use to being primarily transmitted through sex, and the continued weakness of the Moldovan economy had sent an estimated 25 percent of the population abroad to work in Russia or Western Europe, many of them illegally, meaning they had inconsistent – or no – recourse to sexual health services.

Labour migrants from Tajikistan face similar challenges. By the late 2000s, an estimated one million of the country’s population of eight million had left to work abroad, the vast majority of them men leaving for Russia, where Central Asian immigrants often face harsh living conditions, discrimination and little or no legal protection. These conditions combined with difficulty accessing health services have left migrant workers at a much greater risk of becoming infected with a sexually transmitted disease, and then infecting domestic partners when returning home. Conducting ethnographic research in Moscow, the team of Stevan Weine, Mahbat Bahromov and Azamdjon Mirzoev found male labour migrants had a low level of knowledge of HIV and often engaged in high-risk behavior, in particular unprotected sexual contact with sex workers after having consumed alcohol. Meanwhile, the research team found that few women at home in Tajikistan felt empowered to discuss sexual health risks with their partners, given traditional power dynamics within relationships and the sensitive nature of the topic. At the time of the team’s research, the estimated number of HIV cases in Tajikistan was more than 7000, and expected to rise rapidly due to the ‘bridge’ effect created by labour migration.

Relative to many of its neighbours in East Africa, Burundi has not seen high rates of HIV prevalence; however, sexual health issues are at the heart of the country’s most pressing challenge: intense demographic growth. Since independence in 1962, the country’s population has nearly tripled from 2.9 million to an estimated 9 million, and Burundi remains among the 10 fastest growing countries in the world, with a birthrate of more than 6 births per woman. The negative implications of rapid growth are myriad – for underdeveloped systems of agriculture, for the environment, for government service provision of health services and education. With a range of contraceptives offered as part of a free basic package of maternal and child health services provided at health centers across the country, low rates of family planning practice appear not to be so much a question of access as of the continuing preference for large families and pervasive fearof health risks associated with modern contraceptive use.

While creating the conversational space that facilitates the discussion of sexual health issues is clearly challenging in countries where norms are driven by religious or cultural conservatism,it is by no means impossible. As Rwanda – Burundi’s neighbor to the north – and Bangladesh have shown, in vastly increasing rates of family planning practice, strong government communication campaigns can have a significant impact in changing norms even in conservative cultures. In the presence of other barriers, talking, of course, may not be enough to drive behavioral change, but its fundamental importance, as a pre-condition for change, cannot be forgotten – particularly as the global community continues to integrate.

With labor migration becoming a more common phenomenon – creating the space to discuss sexual health will be increasingly important to assuring that both those at home and abroad, in sending countries and receiving countries, have the knowledge and access to resources necessary to lead healthy sexual lives.

Pic Source: Creative Commons