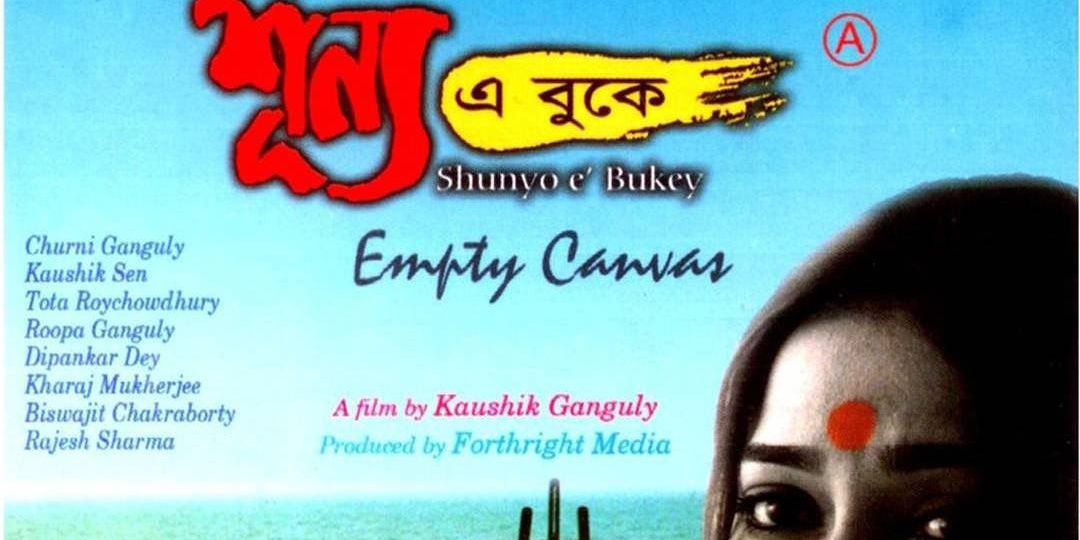

The first sensations that we experience are related to and derived from our body. It is a site of experience, expression and contemplation. The body is a means of voicing our deepest realisations, but how others visualise it can be a source of intense pain. In this context, I would like to talk about the Bengali movie, Shunya E Buke (The Empty Canvas), released in 2005. The name directly relates to a narrative about emptiness and unfulfilled desires. Directed by Kaushik Ganguly, the film challenges sexual and social hypocrisies.

The movie traces the life of Teesta (played by Churni Ganguly) and Saumitra (played by Kaushik Sen) who meet each other while visiting the Khajuraho Temple. Saumitra imagines Teesta to be the epitome of a perfect woman with an extremely desirable body. The two gradually grow close despite the differences in their social backgrounds, experiences, sensibilities, and approach to life. Facing all odds, they marry and decide to live a happy life.

The plot of the movie takes a turn when the wedding night of the couple becomes a night full of shame, revelation, embarrassment and rejection. Saumitra discovers that contrary to his imagination, Teesta is ‘flat-chested’ and that leads him to reject her body deeming it ugly and undesirable. For Saumitra, his muse, his wife, is now reduced to just a body that doesn’t appeal to his aesthetics. Teesta is extremely hurt and dejected, and over time demands a divorce.

This movie draws our attention to the duality of the female body – how even after being a major source of deriving and expressing pleasure, it can also be the cause of someone’s trauma, pain, and rejection. The emptiness that the director wants to depict in the film is not limited to the corporeal, but moves to that of the heart and mind caused by the rejection of Teesta’s body. The ‘empty canvas’ is the ‘empty’ body that is not deemed fit to be desired, and cherished by patriarchal standards. As the plot unfolds, the impeccable acting abilities of the actors reveal to us their characters’ helplessness and that their loss is not only personal but one that has been handed over to them by society.

We see the growth of Teesta as a character from a timid, introverted woman to someone who assertively proclaims to Saumitra that she doesn’t want to live with him, as he has never been able to see her as an individual. For him, she was similar to the sculptures he carves where he is in absolute control of the size, shape and physicality of the body.

Teesta’s demand for divorce and lashing out at Saumitra – that he doesn’t deserve her as he has not understood the tenderness, nuances and the subtleties of the human body apart from it being a giver of pleasure – is symbolic of her lashing out at the patriarchal standards that reduce human beings to just flesh and nothing more.

Years later, we see Saumitra preparing a sculpture on a beach where he suddenly comes across Teesta who is now happily married and is on a holiday with her daughter and husband. Teesta reveals that her spouse and her daughter have accepted her ‘flat’ bosom and appreciate its beauty. For both of them, her body is not a site of comparison or judgment but of immense perfection.

We now frequently discuss on social media the need to remove the shame associated with breasts. Teesta stands to question why, even in 2023, women feel the need to cover their breasts with a dupatta, or why girls in Indian households are taught to hang their bras out to dry covered with a cloth. How and when did the site of nourishment become an object of shame, concealment and regret?

The final scene that shows Saumitra carving sculptures at the seashore relates to the temporality of the human body and how it can never supersede human understanding and emotions. This film asks us: even after being so close to our body, do we actually realise its transcendence through impermanence?

Cover Image: IMDb