The growing encroachment of the Internet and its subsets into our lives has created a world where we reach out for everything online. This has led to the creation of small businesses and industries that help individuals create a profession or allow them to follow their passion. One such booming industry has been the mukbang and food vlogging industry in India.

The word mukbang takes its origin from the fusion of two words – ‘muk ja’ translating to eating and ‘bang-song’ meaning broadcast. It thus means broadcasting yourself while eating. The trend grew in South Korea in 2010 and soon spread throughout the world. The format has changed over the years with mukbangers now recording ASMR videos (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) that make eating noises appealing and satisfactory. Studies have shown that many people find mukbang relaxing and entertaining, and experience surrogate satisfaction while watching people eat. There are hundreds of mukbangers and flood vloggers in India, with individuals earning lakhs of rupees through just eating delicious, and sometimes weird, food. However, those mukbang creators who do not follow stereotypical ideas of gender, caste and class meet with differential treatment.

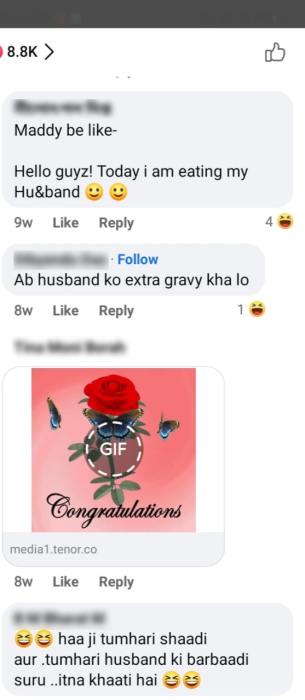

The world of mukbang, as I have seen, is excruciatingly different for women who do not fit the mainstream idea of beauty. Women who do not match the fair and slim code are often bullied, harassed and even abused for their weight, physical appearance, and eating habits, and receive myriad taunts. One such creator is Maddyeats whose videos have garnered over a million views. Her comment section is filled with comments that mock her over “extra gravy”, feel pity for her husband since she eats so much, mock her “XXXL stomach” and tell her to exercise. Most of these viewers express disgust over the oily food, her way of eating and complain how it is dirty when food sticks to her face. On the other hand, comments on videos of creators who do match the mainstream idea of beauty place them on a pedestal and praise how beautiful the person looks, how pretty they are and how they remain slim even after eating so much.

Image Credits: Courtesy of author

It is not just the comment section that is filled with such mockery. The new trend of roast culture in India has taken cognizance of these creators and in the name of humour does not leave any stone unturned to call them ‘fat’, ‘baby elephant’ and so on. This reflects how the creative space is exclusionary and that popularity comes at a price – a price that questions the individual’s very existence and way of life, putting their mental health at stake. The garb of morality that is bestowed on women currently through a new wave of hinduisation (imposing a strict code of conduct as per ‘Hindu’ morals and values) constricts the mobility of women online. The way women and gender minorities claim their autonomy online does not match with the submissive idea of women that has been accepted and normalised historically. Women wearing short clothes and dancing online in videos is seen as a way of broadcasting their sexuality and making it available for people to comment on. Thus, the representation of women comes with terms of reference that allow women to present themselves only in a certain way on the Internet. Even a slight view of cleavage certifies the presenter as someone ‘asking for it’ or being a walking billboard seeking attention. For example, in one of the roast videos of Montii Roy, a transwoman from Kolkata, the roaster complains about the way Montii was eating and that she deliberately wore a deep-necked outfit to show her cleavage. The promotion of this sexist culture by content creators in the name of humour only enables and normalises these kind of ‘jokes’ about women and gender minorities. Seeing their favourite creators make such comments encourages a continuing line of hatefulness where everyone tries their hand at this sort of ‘humour’.

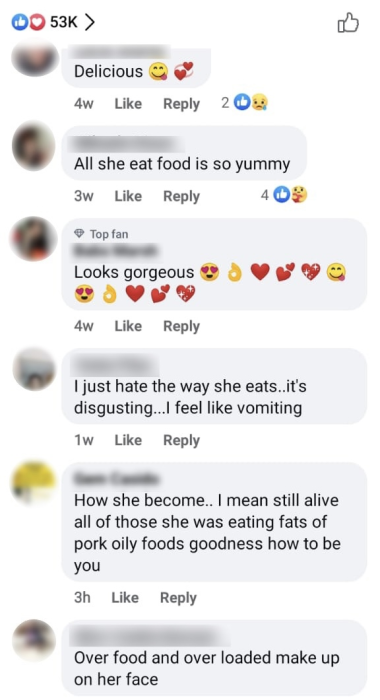

What also irks the audience is the amount of food the mukbang creators eat and the way they eat it. Women are traditionally shown to eat in small portions in a very sophisticated way, one of the so-called characteristics of femininity. But the challenge these mukbang creators pose to this ideal is bringing huge amounts of food to the table and gorging on it, so apparently making the audience ‘cringe’. The idea of aesthetics has compelled us to look through a one-dimensional lens that makes us dump anything remotely ‘different’ as unhygienic or uncultured. What is this idea of sophistication that we are trying to sell?

Image Credits: Courtesy of author

The transition of women from the traditional roles of a homemaker to someone who can take centre stage and create content does not sit right with the flag bearers of morality. Various conditions dictate women’s participation in the eating sequence and processes, for example, women traditionally eat after the men in the family as was portrayed in the film, The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), where women, after the men are done, eat in their used plates and even finish their leftovers. This shift of women becoming creators especially in the mukbang and food vlogging industry helps them take time out for themselves and do something they like. This also becomes economically rewarding for them after a point. As Nivedita Menon writes in her book Seeing like a Feminist: “When you have an entire structure of unpaid labour buttressing the economy, then the sexual division of labour cannot be considered domestic and private; it is what keeps the economy going.”

Women have always been carrying the burden of household work and it is appalling to see how the transition of women from homemakers to creators on the Internet comes with moral checklists and cruel jibes. The normalisation of these comments and ‘jokes’ result in the legitimisation of historic stereotypes against women and other gender minorities. Social media has been a significant reason behind the growing body and facial dysmorphia in young adults. The hate and abuse individuals receive for their life choices are heavily criticised. This can result in individuals resorting to severe forms of dieting, which can exacerbate their anxiety and depression, and potentially lead to tragic consequences. This reel world that looks pitch perfect only hides a world of insecurities and imperfections and makes us think we are ‘inadequate’, ‘unwanted’ and ‘ugly’ if we do not conform to these ideals. According to venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya, “We curate our lives around this perceived sense of perfection because we get rewarded in these short-term signals – hearts, likes, thumbs-up – and we mistake it with worth and with the truth. In reality, though, it is only temporary, flimsy popularity that leaves you feeling much emptier and lonelier than before you did it.”

Addressing these difficulties necessitates work on numerous fronts. Fighting oppressive beauty standards and encouraging acceptance of all body types can both be accomplished through promoting body positivity and inclusivity. Safer environments for content creators can be achieved by promoting respectful online conduct and preventing cyberbullying. Some ways in which this may be done are: Instituting a systematic process of checking and targeting hateful and abusive comments and acknowledging how such behaviour encourages rape culture; taking action against individuals that make sexist and misogynist comments on any creators online. In 2022, the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), a non-profit organization dedicated to combating online hate and disinformation, conducted a comprehensive research study. The study focused on analysing more than 8,717 direct messages received by five well-known Instagram users including actress Amber Heard. According to the findings, Instagram has not adequately addressed the allegations of abuse and fundamental safety concerns faced by women on its platform, despite providing safety tools. Even after reporting abusive messages to moderators, the CCDH discovered that Instagram failed to act on 90% of the abusive messages that were sent directly to the women involved in the study. This points to how important it is for safeguards to be built and implemented. Additionally, creating support networks for those experiencing online violence and increasing awareness about its effects can help create a community that is more supportive and understanding.

Cover Image: Photo by Janice Lin on Unsplash