Home, in the tightest understanding of the word, refers to a place and to some relationships in that place between family members connected by blood or marriage who are physically also sharing a roof. An expanded meaning includes a sense of home as a space of belonging, the way we feel with people that we are not necessarily related to, but with whom we feel kinship, such as friends, neighbourhood community, or a room-mate or flat mate. More often than we think, this expanded meaning of home is where many of us do our happiest bits of growing up. This is where we feel at home.

As an integral aspect of the self, sexuality is at the core of home in the ways in which that home designs space for sexual being, an evolving sexual self, sexual experience and sexual expression, or does not do so, or does so for some members of the home but not for others.

The deep connection between home and sexuality is not just about the physical space and design of home, but also about the access to privacy and control over spaces, information and conversations at home. It is equally about power, perspective and privileges. I was in college when I heard the rumour that a friend’s father had arranged a visit to a sex worker for said friend’s brother just before he was to get married, so he could learn to duck. (Rhyme it.) Decades ago, this horrified the rest of us. All of that information, any part of it and any way that you looked at it. Decades later, I think this was quite practical considering the absence of any form of sexuality education, comprehensive or otherwise available to the young man, at home or outside. But that was a long time ago. Since then, the issue of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE), the role of school and of home, of teachers and of parents and guardians, in delivering and providing access to CSE for young people has become the subject of widespread discussion and debate. It is hoped that this will lead to positive, constructive outcomes.

Did that young man’s first experience of sexual intercourse teach him anything about sensitivity, consent, fun, pleasure, foreplay? It is quite possible that his visit to the sex worker was about learning the mechanics of sex, this goes there, what goes where and then a little bit of practice. That’s necessary too. Somewhere in the past I remember reading another story, describing the experience of a sexologist, when a young couple trying to have a baby, came to him because they couldn’t. The first thing he did was ask them what they do during intercourse. He gave them a ‘girl doll’ and a ‘boy doll’, both sort of anatomically correct, so they could demonstrate. With great confidence, the man took the dolls, put the girl doll down on her back and laid the boy doll down on top of her with the penis at the girl doll’s navel. Sexologists often have these doll stories that would be truly funny if they weren’t also a little sad somewhere. Sex surrogates and their clients build another kind of narrative, where it becomes apparent that for many people, this most crucial aspect of themselves, sexuality, has found no space for expression or evolution, certainly not at home. A sex surrogate works with clients on resolving issues of intimacy and sexuality and this work may involve varying degrees of physical and sexual engagement between client and sex surrogacy practitioner. In another online piece, the client of a sex surrogate says, “I once dated and fell in love with a lovely girl who seemed to be attracted to me. I remember her waiting for me to make the first move sexually, but I didn’t have a clue what to do, so I made up some weak excuse and went home.” He went home. I doubt he spoke to anyone about this at ‘home’. A sex surrogate in a hotel may have helped him more than his home did, to build his capacity to create a home with a lovely girl who is attracted to him. (On another note, I sometimes wonder how life would have turned out if more of us had had the opportunity while growing up at home, to build the capacity to create a home with a lovely girl attracted to us.)

Returning to the rumour in college, one may be reasonably sure though that neither father nor mother would want daughter to learn the way that their son did. Or any other way. Most daughters go unprepared without any theory, forget practice, to learn from. Their husbands are expected to ‘teach’ them, and so all that happens is that the locus of control shifts to another other in another home. Or the boyfriend does the teaching. Or the Internet. Or girlfriends who’ve done it. Or older married sisters. I am not advocating for or against sex workers facilitating sexuality education. I am just pointing out the widespread lack of space for sexuality and learning or talking about sexuality at ‘home’.

Home isn’t home in the same way for everyone who calls it home, and home doesn’t offer equal opportunities, including for sexual experience and expression, to everyone. Depending on the size of housing and family, a home has lots of other information to offer. Books, artworks, curtained-off areas, spaces for the practice of religion and rituals. I have peeped into homes where bedrooms do not have religious images and icons, because you can’t engage in sexual activities in front of such images and icons. It is quite possible that such images and icons may exist in all other parts of the home, kitchen included, but not in the bath and toilet either. Sex, sexuality, nakedness, bath and potty, all relegated to the same status of impurity and things to feel ashamed about. Things to hide away from the gaze of higher spiritual beings and away from the gaze of other human beings as well.

Home is a strange place. Home reflects the world outside, which is after all a place that is a collection of millions of homes, and ideas, amongst other spaces. A peep into each other’s homes is charged with more significance than we consciously apportion to these experiences. This peep, at any age, the age of school and college friends, young adults, older people, married couples, unmarried couples, much much older people, gives the person peeping a lot of information about other lives and relationships. The apps in the head, heart and spirit automatically process this experience and add it to all that we know, about food, interior design, money, manners, occupations, lifestyles and sexuality.

It’s not just about whether sexuality is ever a subject of conversation in the home. It’s about how a home has space on the clothesline for outer garments, shirts, salwars and for socks and men’s vests and undies, but one would imagine looking at this clothesline that the women of the house don’t wear bras and sometimes panties either. That’s alright, bras are a pain. It’s okay not to possess them. But then you’ll visit the bathroom and find them hanging discreetly to dry on hooks behind the door in the dark. There you go. What could that mean? Your undies get the benefit of sun and air but mine must grow mushrooms?

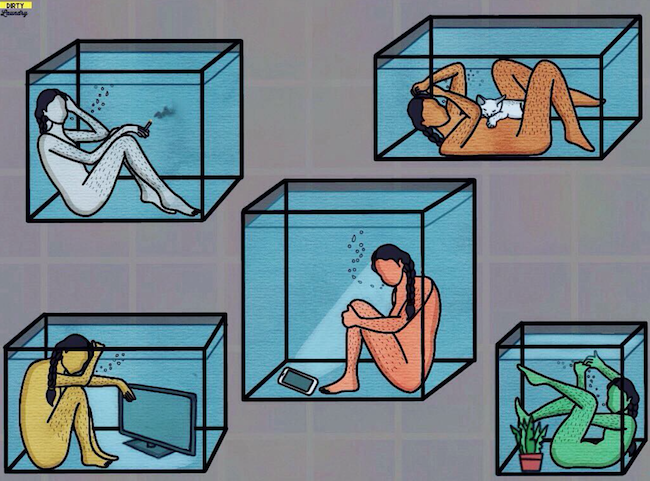

Bras are a great everyday example that the artist Kaviya has included in her series #100DaysOfDirtyLaundry on Instagram where she goes by the name of wallflowergirlsays. Here is a screenshot of her art on Instagram along with much appreciation expressed by the followers of her account. This appreciation is as important as her artistic expression – somewhere her idea of home is connecting closely with the idea of home that is shared by individuals who may be strangers to each other. This idea of home may be in the heads and hearts of many who are not actually able to be this way in their own homes – but wish they could be. It’s a shared idea of home – so perhaps the people who share this idea are a sort of family too and the idea is a home.

Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/BaflOf-hYkr/

In an online article, Kaviya is quoted as saying, “I have many times, during the project, deliberated on openly speaking about certain intense, difficult topics like sexuality, relationships and fears because they felt fiercely personal to be shared online,” and “I have been questioned by my close ones as to what purpose sharing my dirty laundry to the world solved [sic]. But I was, and I am still, convinced how art can be a powerful medium for opening uncomfortable but necessary conversations.”

It is an uncomfortable truth that while something “fiercely personal” should find safe space at home, it doesn’t. This is what makes little gathering places in the virtual world feel like home to many, including many young people, while their family members amongst the older generation wonder what they’re doing on the net. They’re feeling at home. Very few young people wonder where their parents stash the condoms and contraceptives, and in that relationship between parents and children, this is one of the things that makes parents feel more at home than their children do. They’re in control of the things they reveal and the things they hide. Some parents routinely check Internet history, cupboards and drawers to see if young people have a stash of sex stuff anywhere. So if a teen has condoms or contraceptive pills to hide they better hide them well. If that teen is a cross dresser, or negotiating their own sexual or gender identity, things can get really tough.

When I say ‘parents’ I am also conscious of the fact that there lies more than just one aspect of power imbalance in the home. Gender based inequalities are a prevalent, pervasive example of power imbalance impacting perceptions of sex and sexuality everywhere, within and without the home.

In this online piece, 10 Indian Men Recollect The Horribly Sexist And Patriarchal Ideas Their Families Tried To Impose On Them, one of the interviewees says, “I was also the one to be chosen when it came to say, have the favourite piece of chicken, or get to sit in the front seat of the car, next to the driver while my mother and sister cramped up in the back seat, go anywhere and anytime, get to have a say in all the major decisions taken in the family, from which colour of paint to be picked for which room to what car to be bought and even the size of the television bought! My elder sister always took the backseat and didn’t object much — mostly because I was the kid in the house and also because I was the boy — I am only assuming this. I started realising my privileges when I saw my sister taking the backseat for the same things with her husband. I got really mad then but then it all dawned upon me.”

So – ‘taking the backseat’ or sitting ‘in the front seat of the car’ is a way of living that an individual may learn as a life lesson. A relationship lesson. Lessons such as this are taught and learnt at home and in the schools our homes send us to. They are taught by those who lay down the rules by virtue of the positions of power assigned to them, unquestioningly, by unchanging cultures, customs and societies, that are well past their expiry date.In the same online article, another interviewee says, “I guess these things are passed on without much thought. Like two years back, my sister was expecting a child. She had come home that summer and I went and got groceries, so we could all have a nice meal. When I reached home, my mother asked her to make nimbupaani and give me because can’t she see how hot it is. I frantically refused. What I should have said was that I can make my own nimbupaani, please. My expecting sister does not have to do that for me. If your son can’t make his own nimbupaani, then maybe there is something not quite right with him, mom!”

How we are raised at home is more than a matter of groceries and nimbupaani. I recently conducted a training session with adult participants on the subject of story work with children, when an intensely personal, emotional issue leapt out of the closet. Loving oneself. Loving one’s own face and one’s own body. This is impossible, it was felt by many. We are not supposed to love ourselves and we are not supposed to love the way we look, we are not supposed to love our bodies or love the way we are. That is how we are raised, that is our culture and that is the way we do things in our homes. We are taught not to love ourselves, we are taught to love everyone else. We are taught that we are not important, that we are to give importance to others and relegate ourselves to last in line. Many women amongst the participants understood this, knew this, it was an idea and an experience familiar to them. It was home. A home where body image and self esteem, basic concepts within the sexuality framework, are either given no importance, or ignored, or deliberately downgraded. It is precisely these things, body image and self esteem, our evolving sexual selves, that are now being recognized as key aspects of emotional, psychosocial and physical well-being. Shouldn’t these concepts find themselves a comfortable space to be, at home?

Cover Image: wallflowergirlsays