In Ritutparno Ghosh’s film Chitrangada (2012), a scene at the beginning contains the film’s key conceit, an illustration of one of the most piquant ways in which a person is rendered man or woman – when one desires another. In this scene, Rudra, the queer protagonist of the film, is directing a rehearsal of the play Chitra (1914) by Rabindranath Tagore. Chitra, the Princess of Manipur, has been raised as a man by her father, the King of Manipur, since he has no male heirs. Rudra thinks that the dancer playing Princess Chitra hunting in the forest is too dainty in her movements. The dancer attributes this to having to perform the scene in a sari. Rudra is furious, “Sari or trousers does not matter here!” he snaps. “Chitrangada is conditioned to be a man! That’s how she’s been brought up! She is a man, even in a sari! Then in the jungle she meets Arjuna and then she wants to become a woman.” In the play, Chitra decks herself up in silk and jewels, however, in a fashion that may be called ‘unfeminine’ (for woman waits, and lures man to ‘initiate’ love) she accosts Arjuna and declares her love for him, which he declines of course (for man’s desire is extinguished by such unfeminine erotic positioning). Heartbroken, she turns with fury on her masculine self, destroying her weapons, despising her “strong, lithe arm, scored by drawing the bowstring”. She prays to the gods of Love and Spring, Madana and Vasantha and they grant her for a period of a year, great beauty, “the power of the weak, the weapons of the unarmed hand” and the “the play of the eyes”. She is transformed, disguised in appearance and disposition, and in due course, Arjuna succumbs to her pursuit. Their bliss is short-lived; Arjuna cannot shake the feeling that he is in love with a mirage, his heart is “dissatisfied”, and all his efforts to reach her are in vain. Meanwhile, tales of the mysterious warrior Princess, who is both mother and father to the villagers, reach them and Arjuna is very curious about her; Chitra tells him that the qualities and achievements of this princess will evoke ardour in no man. Towards the end of the year, one afternoon, Arjuna asks her to join him for sport in the forest, “Come, let us both race on swift horses side by side, like twin orbs of light sweeping through space”. Chitra is both afraid of this “twinning”, of losing her frailty and her difference from Arjuna (man), and thereby his love. But she is also hopeful. Sensing her ambivalence, Arjuna once again begs her to show her true self to him. Chitra submits to his plea, and the play ends with him embracing her in her original form, “Beloved, my life is full”, he says.

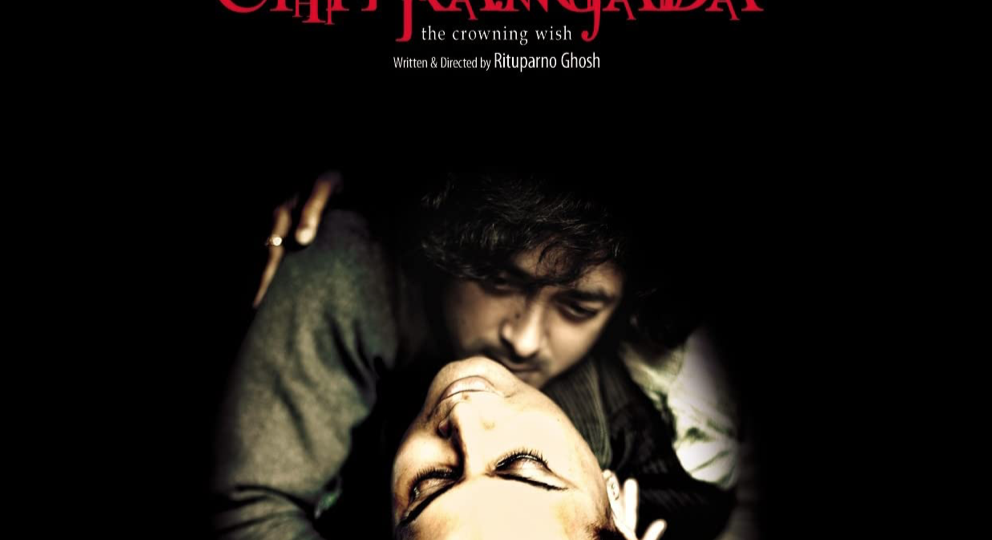

Unlike Chitra, Rudra in the film Chitrangada – as the unfolding story will show – is not so triumphant in his gender-bending pursuit of love. In an early scene, we witness how the haughty, talented and established dancer and choreographer is seduced by a much younger Partho, a drug addict, handsome and manipulative, a drummer in Rudra’s troupe. Their chemistry sizzling, the dynamic identifiably sado-masochistic, the scene has Partho tying anklets on a quivering, initially resistant Rudra, kissing his toes; Rudra, in submission to this act, cries silently, gratefully. Rudra’s wish to be woman is in this manner initiated. The relationship is stormy, Rudy’s (as he is now called by Partho) friends and family disapprove of an evidently exploitative relationship – Partho is unreliable, self-serving, dishonest and unfaithful. The lovers enact many recognizable hetero-normative romantic tropes – the wronged petulant woman pacified via kisses and caresses, the woman too tired for sex who then tries to placate the sulking male lover. Despite himself, Rudy starts dreaming of lifelong love and family (via adoption) with Partho and plans and starts gender-reassignment surgeries. Partho tries to dissuade Rudy, “I love you just the way you are”. “Will you love me less if I become a woman? I don’t want you to love me more”, says Rudy. Partho is unable to bear Rudy’s post-operative frailty and dependence, and cannot find in himself the reserves for bodily care and tenderness that the circumstances demand. He mourns what he sees as the death of the creative, energetic, eccentric lover that he could depend upon. Unwilling, or perhaps unable, to embrace the woman Rudy with her (new) breasts, he leaves her for another woman already made pregnant by him, whom he plans to marry. “Be who you want to be”, he tells Rudy when she asks him one last time whether she should go ahead with the scheduled vaginal reconstruction surgery, rejecting the offer of love and relationship hidden in her question.

***

Some feminists, especially some radical feminists (Andrea Dworkin, Catherine MacKinnon, Sheila Jeffreys, Sue Wilkinson), scrutinising such heterosexual psycho-dynamics have pronounced love to be a four-letter word – to them, desire seems to be premised on an “eroticisation” of dominance and submission and gender is the product of this sado-masochistic play. Feminine masochism is far more easily discernible in all relations than masculine masochism, said Freud. The masculine positioning (not necessarily male) is via doing and the feminine (not necessarily female), via being done to. The one who penetrates and the one who is penetrated the one who looks and the other who invites the look, the lover and the beloved. “This needs to be theorised! But what is the persistence of these categories in queer love?!” bemoans a queer colleague. For radical feminists (like Sheila Jeffreys, Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon), heterosexuality and any gender or sexual expression that is an ‘imitation’ of heterosexual roles, such as butch-femme gender expressions for example, are on a continuum with what they see as modes of violent male sexual behaviour such as rape, pornography and sexual harassment; the latter are not aberrations, but an extreme manifestation of ‘normal’ (hetero) sexual relations. And relations at work, in public places and in family life oppress women, modelled as they are on such power-ridden sexual dynamics between men and women in the bedroom.

But could we look anew at the politics of love in such dynamics? Shifting from questions of whether problematic power-ridden gender categories are reinforced, could one perhaps look for clues to sexual justice and sexual ethics in the freedoms allowed to both partners in the play and evolution of their desire in the material everyday evolution of their relationship?

Turning to the two love stories written a hundred years apart, in Tagore’s play, it can be argued that Chitra and Arjuna allowed for or could accommodate the multiple potentials of a plural self – male and female, dependent and independent, active and passive, the doer and done to positions – in their lovers. Chitra transformed herself for Arjuna’s love, in time embracing herself in tenderness and service to him. Arjuna at first was unable to receive or contain her active desire – he was turned off by an active expression of feminine desire. Yet, in time he reached an expansiveness of self that was not threatened by it, he had been changed by love too. In Chitrangada, on the other hand, Rudy and Partho are the proverbial star-crossed lovers unable to expand their personal horizons to own the other’s desire, and unable to transcend the polarities that define gender Partho, in particular, cannot sustain the integrity of his desire in the face of the queer multiplicities of his lover who can be both haughty and compliant, strong and weak, both someone to depend on and someone who depends on others.

The feminist psychoanalyst Jessica Benjamin, in her book The Bonds of Love (1988), sees heterosexual gender relations that fall into these polarities of ‘the doer’ and ‘the done to’ as arising from the inability of the partners to mutually respond and transform in relation to one another. Since either party cannot be both at any one time, togetherness then depends on splitting into complementarities/polarities such as doer and done to, with patriarchy defining those taking up the doer position as masculine and the done-to as feminine or as subject and object. Instead she posits intimacy as only possible where subject relates to subject, where the tension that such a relationship creates for either party can be sustained by them, without devolving into ‘doer’ and ‘done to’. Perhaps, rather than the avoidance of gender categories altogether, such a play of masculinities and femininities in intimacy can aspire to represent one imagination of ethical erotic relations and ethical queer relations.