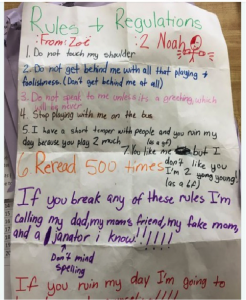

Ten-year-old Zoe is an internet celebrity because she wrote a letter to Noah, possibly the same age as her, that told him clearly, amongst other things, “Stop playing with me on the bus,” and, “If you break any of these rules, I’m calling my dad, my mom’s friend, my fake mom, and a janator (sic) I know!!!!!!”

Boundaries serve purposes. They mark territory, they frame identities, they tell you what is yours and tell others what is not theirs. They keep in things, they keep out things.

In this video on sexual harassment in India, the Breakthrough team spoke to young people who aired their views on harassment, quite a few of which were about violating and disrespecting boundaries. Some of the voices in this video have said things like:

Girl: “On Facebook they will keep on poking us.”

Boy: “Never accept ‘no’ from a girl or you won’t get her.”

Girl: “Who are you to comment?”

Boy: “If she’s pretty we harass her, if she’s useless, we leave.”

Sometimes, to some people, boundaries are challenges. “Never accept ‘no’. Don’t let a boundary stop you. You own everything.”

In recent years, khap panchayats (quasi-judicial bodies in a union of villages) from some states of India, particularly Haryana and UP have passed orders banning girls from wearing jeans and using mobile phones. These are now well-known attempts to enforce a boundary and have caused much debate and furore.

There have been many cases where khap panchayats have prescribed the boundaries of behaviour and conduct for girls and unmarried women, attempting to disconnect them, quite literally, from the world outside the boundary:“Girls get spoiled and get involved in relationships with boys at a young age because they use phones. This further leads to crime against them.” Many people now want the khap system banned.

Somebody, not always us, chooses what our boundaries keep in and keep out. So, somebody, not always us, owns our boundaries. Owns us.

Who creates boundaries? For whom? What do they keep in and what do they keep out? What are the identities created for us and for other people to see?

The concept of boundaries has become mixed up with the concept of being bound in a this-far-and-no-further way. They have become enclosures, aquariums, cages built for those who inhabit them, but not necessarily built by them. While Zoe is the owner of her own boundaries with reference to Noah and she clearly spelt out the do’s and don’ts as well as pointed out her support system just in case Noah remained undeterred, the young people in the Breakthrough video who never take “no” for an answer and the khap panchayats who take away the right to use cellphones from girls and women, point to two different kinds of approaches to owning boundaries. In these latter two illustrations, boundaries are owned by the possible or potential perpetrator of abuse or one at risk of violating the rights and freedoms of another. Here the boundaries appear to be drawn to dare those on the other side, or are drawn to restrict the one who is seen as vulnerable.

In the discussion and debate on sexuality education for young people with disabilities, teaching the concept of personal space and boundaries is closely tied with strategies to empower the individual against the possibility of abuse – sexual, emotional, and physical. Thus far, all the focus is on the individual’s learning to create boundaries against those who may violate them. There is also the conversation about children who are not neurotypical, who must learn the concept of space and touch and behave in ways that are appropriate and acceptable. The boundaries we draw for a person with a disability often imprisons that person in a space where the identification and expression of sexuality is completely denied. That person with a disability neither owns this boundary nor their sexual selves. Put in another way, this means that while a neurotypical child also learns appropriate behaviour and expression of love and affection, good touch, bad touch, body and boundaries, learns concepts of private and personal as opposed to public, they will also learn about spaces in their lives where relationships and sexuality unfold. A child with a disability will mostly live within boundaries that do not give access to any such spaces.

Abuse is a concern, so we return to boundaries. We need them for protection and for identity. We need to teach ourselves and our children how to set boundaries so that we do our part in deterring and stopping other people, so that other people don’t kiss and touch us without our consent, don’t stalk, don’t read our mails and text messages, don’t insult and humiliate us, don’t assault, don’t rape, don’t abuse our vulnerabilities. Yes, there will always be those who try and those who do abuse others, who repeatedly transgress and violate boundaries. There are strategies that have been suggested for dealing with such people, some of which are:

Do we focus too much on boundaries because we are forced to live a life driven by the need for protection from abuse? Are perpetrators of abuse deterred by boundaries? Are they deterred by the threat of being found out and punished? Perhaps we need a re-think about the reasons for a boundary. If covering the face, not carrying a cell phone and wearing traditional Indian attire stopped a transgressor from groping, molesting, harassing and sexual assault, they could be included as worthwhile tools of the boundary trade.

For a moment, let us assume abuse is not a concern. Would we need boundaries then? Or could we be free of them, or re-draw them as we please, migrating from space to space across stages of growth and maturity, and emotional, sexual, intellectual, physical and spiritual experiences? Or just locate ourselves in a non-migratory way in a spot that suits us?

If we were the owners of our boundaries, would we be the owners of our multi-dimensionally evolving, changing, sexualities? Would we be the owners of our selves? Would we respect that others were the owners of their own selves?

Cover image courtesy The Times of India