Maya Sharma is a feminist and activist who has been passionately involved in the Indian women’s movement. She has co-written Women’s Labour Rights, a book on single women’s lives. She is currently working with Vikalp Women’s Group, a grassroots organization in Baroda, Gujarat, that works with tribal women and transgender people.

TARSHI volunteer Anjora Sarangi interviews Maya about her experiences with and observations about various people’s movements in India.

Anjora Sarangi: Tell us a little about your journey over the years including your involvement in various people’s movements like the labour movements and women’s movement.

Maya Sharma: I got involved in the movements quite late: in my 40s. My first experience of a different way of thinking, away from traditional patriarchy, was when I encountered oppression in my own personal life as a married woman. At that time, I did not have any answers for what I was experiencing. I started going to a women’s group called Saheli and it was wonderful to be in a group of women where one could express oneself freely.

I had been a literature student in Delhi and my first exposure to feminism was through a book called The Female Eunuch (by Germaine Greer). To read literature that rang a chord in my heart was very revolutionary. My first passionate involvement in people’s movements was with the women’s movements. From then on, I started working in this field.

I got interested in labour issues while working in bastis (slums). There is a lot of disparity between the formal and informal sector and women are mostly involved in the latter – in home-based work, in the construction sector, etc. I noticed that women didn’t buy groceries or other essentials in large quantities during the day because it is only at the end of the day that they get their wages. These things affected me immensely, especially since I saw that women were working hard but were not being compensated adequately and on time .

Therefore, when I got an opportunity to work in a central trade union, I decided to get into labour issues. I am from the women’s movement and am constituted by that movement, so that was an essential part of me and I brought that consciousness to the everyday work in the union. Labour unions are very hierarchical in nature and so women are left behind. I am no longer very active in the labour movement but not much has changed; there is hardly a push for women by labour union leaders.

AS: Would you concur with the statement that women or sexually vulnerable communities have been on the sidelines of people’s movements such as trade union movements or tribal movements in India?

MS: It is difficult to use one brush for all movements, but in broad terms, I do agree that those identifying with different sexualities have been marginalised. I think women involved with other women specifically cannot come out because it still continues to be a taboo in India.

AS: How did Vikalp Women’s Group come about? Could you share your personal reasons for deciding to be a part of a project that works for tribal women and the LBTI (Lesbian, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex) community?

MS: While doing research for my book Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India, I noticed that women were very isolated and alone in far-flung areas, and one saw the need to write about them and bring them together. That was one of the reasons why I joined Vikalp; because it was very willing to take up this issue, unlike several other organisations. Secondly, some people at Vikalp were actively working towards the formation of the union within Mahila Samakhya, which is a government-run programme in which workers, called volunteers, are paid but are not given other benefits. Our effort was to create a union and ask for benefits. The struggle also has another history – a worker in Rajasthan was raped and there was a protest surrounding it but when women wanted to take leave and join in the protest, the state government did not allow it. It was then that a realisation dawned that the state would not concede to people’s demands. Therefore, union formation became very important.

There was a need felt to take on the issues that Vikalp did, be it with tribal communities, on the issue of silicosis, or on HIV and AIDS. I began to work with Vikalp after the end of my research.

AS: Vikalp’s primary stakeholders are rural and tribal women. Can you tell us more about your experience with this particular demographic?

MS: There are many intersections in these communities and groups and these intersections constantly change the rules of oppression. It is not a constant. Though it is changing, tribal culture has historically had a greater acceptance and tolerance of dissent and alternate ways of life. Agriculture is a dominant profession among tribal people but it is seasonal in nature, so people experience unemployment across phases. Many tribal people are in same-sex relationships and it is known to the society but if you openly confront them then it can become a problem. However, there are subtle differences that one notices only when one interacts intimately with the communities. Isolation exists because not being a heterosexual couple leaves one alone, an aberration to the norm. There is no reflection of a couple’s same-sex relationship in the wider society; a validity that is critical.

Coming out is not a major concept in India as we do not have a verbal or visual culture. At the same time, society is very hierarchical in nature. For example, there was a same-sex farmer couple that we came across in a rural interior area who had eloped initially but had come back to the village. In the holi season when the harvest is cut, newly wed couples in the village take a round around the pyre, and this practice was carried out by this particular couple. No one questioned it and it was kind of expected. However, no one formally said that they accept the union though there are rituals which affirm the relationship.

In Gujarat, tribals in same-sex relationships and those who are transgender are getting jobs as say home guards or in beauty parlours with the spread of urbanisation. Jobs are very important from a family point of view because transgender people are often made to feel that they are distinct. But once the money starts coming in, there is far greater acceptance. Some parents are accepting of differing relationships as long as they are not visible to the larger community of relatives and elders. We have known cases in which a father has given property to a transgender person because he trusted them and believe that they would take care of the property. At the same time, there are instances in which state interventions have not been favourable and people have suffered.

AS: Which are the sexual minorities that are most affected by violence and discrimination in your understanding?

MS: I think everyone is affected by violence and discrimination. There is no black and white.

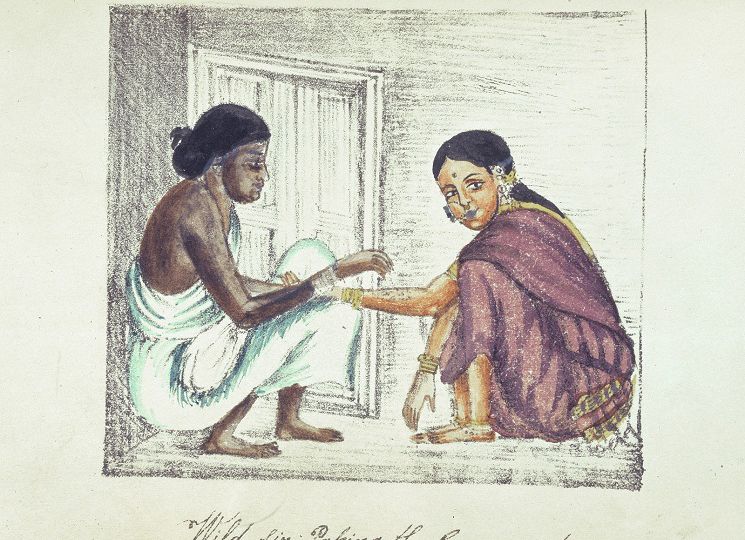

Cover image courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Human Rights

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें