As someone who has worked on sexuality and gender related issues, HIV and AIDS has been part of the larger canvas of issues that I have been concerned with. There is an interesting tension between health and service delivery, especially around HIV and AIDS, primarily focused on so-called ‘populations at risk—the sexworker, intravenous drug user, MSM (men who have sex with men), TG (transgender)—and on human rights advocacy related to LGBTI rights. In the former, the focus is on delivering crucial health services, awareness around HIV and AIDS, counselling, and ensuring safer sex practices such as the use of condoms. This can be contrasted with the ‘human rights’ approach, or the focus on identity politics, demands from the state, and civil and political rights such as the right against arbitrary arrest and blackmail, the right to privacy and gender expression. These tensions can be seen within the NGO sector where organizations working on HIV and AIDS are often criticized for taking the safe route, and not challenging the state enough.

Of course, both these approaches cannot be separated from each other. It was the onset of HIV and AIDS funding in India in the ’80s that allowed for community spaces for LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex) persons to be set up, and the human rights implications of HIV and AIDS in terms of socio-economic rights and the stigma and discrimination that people living with HIV and AIDS face cannot be underestimated. Large organizations that deal with HIV and AIDS like Naz Foundation in the north (of India), Humsafar Trust in the west, and Sangama and its affiliates in the south have been doing both HIV and AIDS prevention work as well as rights advocacy including against Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, the law that criminalizes “unnatural” sex (read as not involving the penis penetrating the vagina) in India. In fact, one of the events that led up to Naz Foundation filing the 377 case in the Delhi High court was the arrest of four HIV and AIDS outreach workers in Lucknow in 2001 under Section 377. The local media portrayed these arrests as the busting of a sex racket, and it was only after the intervention of lawyers from Delhi that those arrested were able to get bail.

The Delhi High Court, in its Naz Foundation judgment that declared 377 unconstitutional, relied on two main strands of arguments—the first dealt with the right to health, stressing the impact that the law has in preventing HIV and AIDS prevention work, a lot of which was being done by state agencies such as the National AIDS Control Association (NACO). Thus this argument is premised on the fear of the law, i.e. criminalizing populations at risk only makes them go underground. The lawyers in the case were able to exploit the fact that the two Ministries of the Central Government—the Health Ministry (under which NACO functioned) and the Home Ministry took divergent views on the case. The Union Health Minister at the time, Anbumani Ramadoss, (who is a trained medical doctor) had made public statements in favour of the repeal of Section 377. However, the Home Ministry and the government’s lawyers stuck to the position that Section 377 was needed to prevent the ‘breakdown of morality’ in the country.

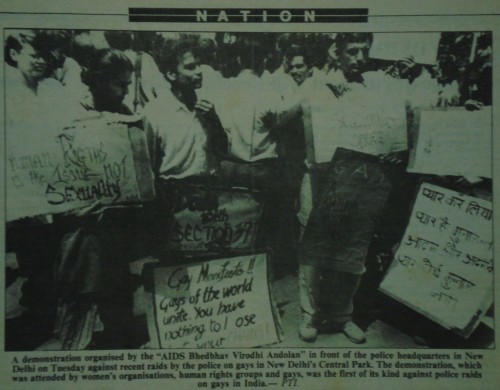

The second strand of argument before the Delhi High Court was the impact of the law on the right to equality, privacy, and liberty of the community of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) persons in India. Here, the focus was on how the state violates rights of those who identify as LGBT, through arbitrary arrests by police, blackmail, harassment, and providing legitimacy to stigma and discrimination. Through numerous personal testimonies, those arguing the case were able to convey the extent of discrimination and harassment that LGBT persons faced on an everyday basis.

Interestingly, one of the organizations that opposed the decriminalization of homosexuality both in the High Court and Supreme Court falls in the category of what we would call ‘AIDS denialists’, those who believe that HIV does not cause AIDS. The Joint Action Council, Kannur, (JACK), a Delhi-based organization, was one of the most vocal opponents of decriminalizing homosexuality, and their critique of government HIV and AIDS policy varies from the outlandish (HIV as not having any substantiated link to AIDS) to the debatable (Is there a skewed policy towards HIV and AIDS funding, taking attention away from other problems that the health sector in India faces?) In a way, what JACK did was to question the link between these two strands—the debate around public health, HIV and AIDS, and ‘at risk’ populations, and that around citizenship rights for LGBT persons.

In 2013, the Supreme Court reversed the Delhi High Court’s decision, recriminalising LGBT persons. One of the interesting exchanges that took place between the judges of the Supreme Court and lawyers arguing for the decriminalisation of homosexuality was the lawyers trying to explain the basics of anal and oral sex to the judges, who already seemed quite uncomfortable with the long discussions around sex and sexuality. The judges, in turn, lectured the lawyers and their captive audience in the courtroom on incidents of vulnerable young girls trafficked into prostitution. The Supreme Court dismissed statistics and reports submitted by the petitioners including a damning 2002 report by Human Rights Watch on the negative impact of criminalisation of homosexuality on HIV and AIDS prevention work, and statistics showing that the percentage of HIV-positive persons amongst the MSM community was much larger than in the general populace.

It is now two years since the Supreme Court reversed the High Court’s decision. While the Supreme Court decision has been challenged through a curative petition, it is essential that legislators both at the state and central level wake up to the risks that Section 377 poses and repeal the law if the courts fail to do so.