Being single carries stigma. It is considered such a failure after a certain age that it messes with our self-worth, our identity, and confidence. And although it may be seen as an assertion against patriarchal norms and normative heterosexual relationships, it doesn’t give us the strength we need to be single because we lack enough narratives in mainstream discourse that reinforces aspects of singlehood. One such narrative that I recently read is The Liberation of Sita by Volga*, and I feel that it is a phenomenal work in all the reimaginations of mythology till date, for several reasons.

The book is a collection of short stories, with Sita from Ramayana as the protagonist who meets several other women; women who are under-represented in the epic like Ahalya, Surphankha, Renuka Devi, and Urmila. These stories are not in chronological order as they show life of Sita before and after exile, so it doesn’t give us a comprehensive idea of the storyline but instead talk about these women who represents singlehood in a different manner and the way they give strength to Sita to overcome her misery.

Sita, abandoned by Rama twice, is on a journey to find the strength to live alone, overcome heartbreak and sorrow, and in the process, either meets these women or recalls their profound advice from her earlier journeys. In this narrative, Sita, although married, doesn’t have a companion, a partner to rely on, and finds support in other platonic relationships and in sisterhood. In this narrative, Sita finds solace in these women and understands a different perspective about beauty, self-worth, authority, self-reliance, and toward the end, finds liberation from society and marriage which were the root cause of her sorrow.

After Rama leaves her at Valmiki’s Ashram in the forest, Sita meets Surpankha, a demoness and Ravana’s sister, whose nose was cut off by Rama and Lakshman. Surpankha was proud of her beauty and after the mutilation, found it difficult to love herself and ‘find’ love for a long time. After a long battle with her own self, she found a new meaning of beauty in nature and dedicated herself to nurturing a garden. She eventually met a man in whom she found a companion, but while sharing this with Sita, she says, “I’ve realized that the meaning of success for a woman doesn’t lie in her relationship with a man. Only after that realization, did I find this man’s companionship.” (pp. 13) We often rely on our romantic partner for validation or look from their eyes at ourselves to adjudge our own desirability, but in Surphankha’s case, this only gave her sorrow as she had been ‘rejected’ multiple times. It’s only when she found her self-worth that she was able to have a fulfilling relationship with another individual.

Ahalya is another such woman Sita meets in the course of her life. Ahalya was married to Sage Gautama and was famous for her beauty, unlike Surpankha after her mutilation. Indra, disguised as Sage Gautama, slept with her and enraged at this, Sage Gautama turned his wife into a rock. Years later, when Rama looks at the rock, Sage Gautama’s curse breaks and Ahalya takes her original form again. She, however, is shunned by society and called ‘characterless’. In conversation with Sita, she mentions that people are often vexed by the question if she had seen through the disguise, but to her husband, it didn’t matter. “His property, even if temporarily, had fallen into the hands of another. It was polluted.” (pp. 26). Ahalya, married, doesn’t have a companion. Sita, too, is in a similar situation. Then, a relationship or the lack of it is not a determinant of singlehood. It is more to do with having a partner who stands by you through thick and thin and supports you when you need. Lacking it in her relationship with Sage Gautama, Ahalya turns to herself to find the strength that she needs. Does a relationship then end singlehood?

Ahalya represents autonomy. She says that it’s easier for society to deal with a woman who accepts her ‘mistake’, as there is atonement for every sin. If she claims that she has not wilfully made a mistake but was manipulated, she is seen as a victim and is forgiven. But if she does not give any explanation for her actions, neither accepting nor rejecting her ‘mistake’, society finds it difficult, as then, its judgement doesn’t keep her in her designated space and holds no value for her. When asked if her husband has that authority, she only replies, “Society gave him that authority, I didn’t. Till I give it, no one can have that authority over me.” (pp. 28) She advises Sita to not agree to being put to trial and later, to not take decisions for Rama’s but rather for her own sake. One of the problems of being single for a woman is her identity, as her identity is most of the times relational and not stand-alone. She is someone’s daughter, sister or wife and the moment this identity ends and a personal one begins, there is a sense of loss.

Ahalya says, “You means you, nothing else. You are not just the wife of Rama. There is something more in you, something of your own. No one counsels women to find out what that something more is. If men pride in wealth, or valour, or education, or caste-sect, for women it lies in fidelity, motherhood. No one advises women to transcend that pride. Most often women don’t realize that they are a part of the wider world. They limit themselves to an individual, to a household, to a family’s honour.” (pp. 39)

As Ahalya represents authority over herself, Renuka Devi represents personal space and a personal world. Her husband has ordered their son to kill her because he thinks she has been disloyal. The son follows his orders and slashes his mother’s neck, and she is later healed by women in the forest. Since then, Renuka Devi has been thinking about the consequences of giving herself completely to another person. “A woman thinks she doesn’t have a world other than her husband’s. True. But someday that very husband will tell her that there is no place for her in his world. Then what’s left for her?” (pp. 52)

In the penultimate story, Sita recalls her reunion with her sister, Urmila, who was married to Lakshman. He had left to accompany Rama on his exile without having a word with his wife or bidding her farewell. Urmila, in those fourteen years, came to realise that power is the cause of unhappiness. The only way to liberation is autonomy, to have no one command you and to exert power over no one. To be self-reliant and self-sufficient. She doesn’t shun her relationship with Lakshman but wonders if he will accept her as she is.

Sita learns from these women, finds companionship at different times, as well as the assurance that she isn’t alone in her suffering. These women, including Sita, our protagonist, were in committed relationships, yet none could rely on their partners for support of any kind. Then, how do we define singlehood? Having a partner doesn’t solve most of our issues and so to have one should not be considered a success either. The goal has to be about ourselves and we need to take care of ourselves before we care for others in life. To depend on someone for our self-worth, identity and for validation is not the only way to happiness and sometimes not a happy path either. Once we depend on ourselves for that we might be able to see ourselves, our actions and others in a different light and maybe then we will be in a better position to love someone for who they are, accept them, and still remain autonomous.

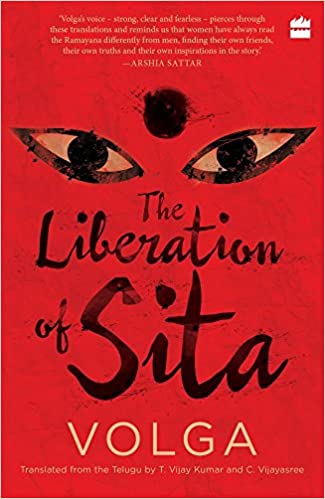

* Volga’s The Liberation of Sita. Translated from Telugu by T. Vijay Kumar and C. Vijayasree. 2016. Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, Noida, India.

Cover Image: Amazon