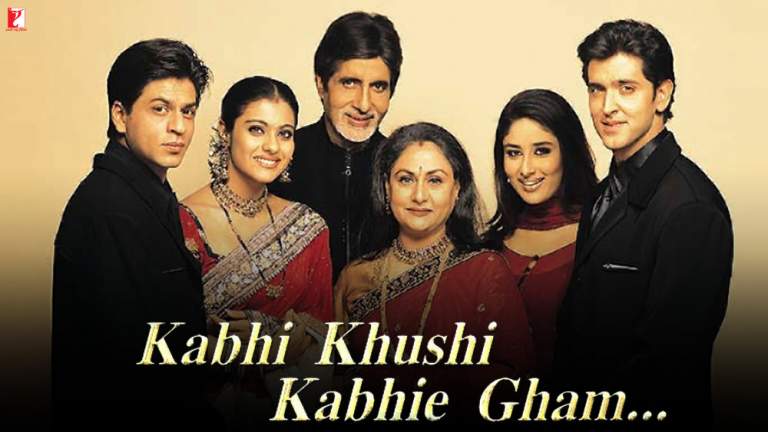

Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham is a 2001 hit Bollywood movie featuring many of the industry’s big league players like Kareena Kapoor, Kajol, Hrithik Roshan, Shah Rukh Khan, and Amitabh Bachchan. I am a PhD candidate in Anthropology at the George Washington University in Washington, DC who tasked myself with developing a class on contemporary South Asia for my department, which included this film. I wanted to include a typical Bollywood film to study media and representation in South Asia. When I mention to students that we will watch K3G, as it is called in shorthand, to explore media in my Anthropology of South Asia class, students who are familiar with Bollywood and the film itself usually respond with groans and incredulous faces. They say they cannot believe we will watch a movie believed to be so silly and overdramatic in a university course. The last time I taught this class, there was almost an even mix of second-generation South Asian students and non-South Asian students encountering information about South Asia, including Bollywood, for the first time. While there are many studies of Bollywood and the particular genre of film within which K3G fits, I call upon the experiences of two second-generation South Asian students to understand their experiences of viewing the movie in my Anthropology class through an analytical lens of how Bollywood (re)presents socioeconomic class and gender.

The movie has a reputation of being a ‘stereotypical’ Bollywood film with lengthy and large-scale flashy song and dance sequences. K3G takes audiences through the domestic dramas of two families living in or near Delhi, and then in London. One family is extremely wealthy and the other is more “salt of the earth” and socioeconomically disadvantaged. Over the course of three and a half hours, the audience sees twists and turns develop in the plot and in the relationships among characters through over-the-top portrayals of romance and betrayal – common ingredients in Bollywood movies. I spoke with GWU students Sabrina Patel and Vishal Nyayapathi about their experiences watching the film through our class topics. Sabrina is a senior graduating with a major in International Affairs with a concentration in Conflict Resolution and Asian Studies, along with minors in Chinese, Sociocultural Anthropology, and History. Vishal is a Sophomore studying Public Health, Communication and Anthropology.

Overall, our discussions revealed that the representations and concepts of socioeconomic class were used to exaggerate the drama between love interests in the first half of the movie but were then erased in the second half, when some of the protagonists move to London. We discussed how this shows a diasporic dream world of living abroad. What became far more overt and exaggerated in the second half of the film, which takes place in the UK, was extreme representations of gender and nationalism. These contrasts were specifically portrayed in the differences between Kapoor’s younger sister character and Kajol’s housewife and older sister character. Kapoor’s character takes on a fully “westernised” persona wearing very sexualized skimpy clothing, which her brother-in-law comments on unfavourably. Kajol plays an extremely nationalistic character wearing only sarees and performing daily Hindu rituals. We all were shocked to realize we could not remember the name of her character, and she is therefore more of a stereotyped representation of Indian tradition and morality through femininity in the second half of the movie. These sisters exemplify both a longing for homeland and a belonging to a diaspora, while the class positions and disparities become erased once the characters move away from their families in Delhi.

In my class, I included K3G in my syllabus as a conclusion to a unit on media and technology to summarize discussions tying together previous weeks’ readings on media representation, gender, and nationalism. Sabrina and Vishal both noted how my positioning of the film rendered cringe-worthy, certain aspects of Bollywood they previously had taken for granted or viewed as quaint, Indian aesthetics in what they believed was an inconsequential form of enjoyable entertainment calling them back to their childhoods or time spent with their South Asian relatives living in the United States. What follows are excerpts from my discussions about the film and viewing the film through anthropological lenses with Vishal and Sabrina.

What were you already familiar with from K3G?

Vishal: I remember the songs for sure, because that is stuff we would hear at family parties or on car trips. Even though we used to have the DVD, I think, I didn’t remember the plot at all. I remember the actors but this was the first time I actually paid attention to the plot. I think that after years of developing a critical lens, it was just horrible to watch this movie again.

Sabrina: I had watched this movie a bunch of times before this class, mostly with family. I had watched it so many times before. For example I would have it on in the background while doing homework and listen to the songs. Prior to watching it in class, I remembered it more for the funny dialogues and music.

What stood out to you from this movie?

Vishal: Gender, religion, and nationalism were definitely the three biggest things that I think stood out to me. Nationalism was definitely something we talked about in our class, but it was also a shock to see how being “western” was portrayed as being more forward. And those characters who are more “western” also have more money because they have access to English and are involved in very capitalistic, “westernised” businesses. The big Bollywood movies, like K3G, were fueled by these kinds of post-liberalisation politics that mix nationalism and very particular aspects of western culture. So I think Kapoor’s character is embracing this western coded, sexualized gender form and then there’s a juxtaposition between her and her sister, who is the nationalistic one, conflated with tradition.

Sabrina: More analysis definitely went into watching it in class, but I think going through our discussion on socioeconomic class made the stereotypes very clear. Kajol’s family’s socioeconomic status was very contrasted with the other family at the beginning of the film. In the one song where it is both of the fathers’ birthday parties, not only was socioeconomic class highlighted but also religion. So in that song and in those scenes, within socioeconomic class, you could see the interconnections with religion as well – being that the more poor family lived very close to Muslim families, though they were Hindu themselves. I think that song was really important for showing why the relationship among the two protagonists was fraught and why the two families were so different, even though they were both Hindu. Because it showed how socioeconomic class inhibited the acceptance of their relationship, and that song was perfect for making that apparent and tying it to other aspects like religion.

How did it feel to watch K3G in a classroom setting versus with family or friends?

Vishal: I feel like this movie doesn’t stand out for my parents. I think something like K3G stands out much more for diaspora kids, who are the ones who grew up watching this kind of film. This was a way to have aesthetically Indian values but to not get into anything deeply critical about those values. These are very different kinds of films than the ones my parents grew up on, which were artistic and dramatic in different ways. And in a classroom you have to criticise it more. If I’m at home, I will definitely have those ideas of critiquing the films, like one we recently watched at home that was very nationalistic, but I keep my opinions to myself because I do not want to start any fights with my family. In a classroom I’m much more comfortable speaking up against the movie. I also can’t speak for all the other South Asian students in the classroom, but because of the racial and national dynamics in the classroom setting, I felt a pressure to almost explain ourselves as South Asians. Not that the movie represents all of us, but there are assumptions that these kinds of movies bring up about South Asian-ness – like being conservative and nationalistic. So I felt the need to be openly critical to prove that this isn’t how everyone is thinking, whether or not I wanted that to be a motivation in my being critical of watching these kinds of Bollywood films in a class setting like ours. I think K3G sits in this weird in-between audience because it seems targeted much more to the diaspora or about a diaspora.

Sabrina: The crux of the film was that the protagonists came from two different (socioeconomic) worlds. When I watched the movie before, I just thought the families did not like each other and watching it in class, I saw much more of how those worlds and characters were compared more obviously through class and not just personality differences. Something else that stood out about watching the movie in class was how the protagonists’ socioeconomic class changed when they moved to London. Something I know about my family moving to the United States was that you don’t automatically get rich, and the family in the movie seemed to be automatically in the top 1% of London. I think that diaspora which is a common theme in Bollywood movies is not a realistic representation. Since I’d already seen this movie before I think it helped me to get past a lot of what was may be very confusing for students watching a Bollywood movie for the first time.

Overall, viewing Bollywood through Anthropological lenses that examine socioeconomic class, gender, and media representation allow for new analysis of iconic films like K3G. From my end, whenever I bring this activity to my classes I learn a great deal from students who re-encounter these films from their childhoods. Watching K3G with my students brings forward new ways of understanding how concepts like socioeconomic class, gender, sexuality, and diasporic imaginaries are embedded with subtle messages of morality and longing and how these messages are ingrained in our Bollywood viewing experiences.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।