I must begin by saying that the discourse on sexuality has largely taken a tradition v/s foreign culture debate in India. Those who vouch for sexual freedom and justice are often labeled as akin to foreigners or outsiders adulterating one’s tradition and culture. In some of the country’s most conflicted regions, activism on issues of sexuality (if it’s aligned to human rights) is both a risky affair and one of secondary importance in the midst of larger socio-political and historical issues. The topic of human rights tends to center on gun violence, AFSPA, statehood and insurgency. LGBTQ rights may have created its own narrative, but sexuality per se is far from being a comfortable subject of conversation.

Lawlessness is the law in Manipur

Lawlessness doesn’t mean an absolute absence of law but law taking a different course altogether, prohibition of certain laws and/or creation of certain others, and violation of law both by legal institutions, state actors and the public. The Armed Forces Special Protection Act (AFSPA) that technically gives special power to the Indian Armed Forces to fight insurgency in disturbed areas has also provided impunity to the forces in cases of human rights violations and it is a glaring example of domestic law that violates human rights. During the Manipur-Naga ceasefire conflict in the early 2000s, the state was literally shut down, civilians were killed and President’s Rule was imposed. The burning down of the State Library and the attempt to burn down the Assembly are clear examples of a frenzied public taking the law into its own hands. On the other hand, extra-judicial killings, legal cases that have gone off the record or are pending, are instances of the law being violated or manipulated by legal institutions or allegedly the government itself. It is then very unfortunate, yet understandable, why, on the one hand, people are naturally drawn to or are occupied with issues of extra-judicial killings that are occasionally presented in court rooms and played out in state media channels and newspapers, human rights issues and territorial conflicts, and on the other hand, why the violence, lawlessness and the absence of justice are normalised. In the midst of such overpowering and all-encompassing issues, where, when and how can one place struggles for sexuality and human rights?

Informal Law and Sexuality in Manipur

Informal law often takes the course of the idea of mob or social justice in Manipur. Sexuality is such a taboo subject that one may be publicly persecuted by local organisations and associations for an intimate or sexual act between consenting adults. As I have outlined in an interview with In Plainspeak, this persecution takes various forms. There is a culture of “keinakatpa” (forced marriage) in Meitei society (Meitei is the way the locals refer to the majority ethnic group in Manipur). If a man and woman are caught in a ‘compromising position’, suspected to have been intimate, be it in a public or private space (private space is also liable to intrusion), then they are forced into marriage by the local Meira Paibi (women’s group). Also, vigilante groups, in collaboration with Meira Paibis, conduct ‘restaurant drives’ where they hunt down lovers probably being intimate inside restaurants and punish them through forced marriage or by defaming them in public. This doesn’t mean that people are not having sex at all; there are other spaces, such as hotels exclusively accessible only to the rich.

A woman accused of being a porn star and a mayang (outsider) allegedly involved in the making of a porn film were killed by an insurgent group in Manipur in the late nineties. The group allegedly stated that this was a punishment, and issued a statement to the public which said that imbibing ‘outside culture’ (pornography) may call for such actions. This was just prior to the banning of Bollywood films in Manipur in 2000 by the Revolutionary Peoples Front. The Manipuri Digital Film industry was born overnight following the ban. Hugging (to be precise, a woman’s breast is not supposed to touch a man’s body though this may have changed to an extent recently), kissing or other intimate acts are not shown onscreen, probably reflecting public attitudes towards intimacy and sexuality, reaffirmed and reiterated by film censorship bodies.

LGBTQ Movement in Manipur

Despite the state’s socio-political crisis, people have been putting up resilient fights. Resilience is an ability acquired after having been living under extreme duress. In early 2000, probably one of the first gay marriages in the country was publicly announced by a couple who decided to marry in a private ceremony in Imphal though the police and local public intervened and separated them a few days later. The decade-old struggle of the transgender community including All Manipur Nupi Manbi Association (AMANA), Empowering Trans Ability Manipur (ETA), All Trans Man Association Manipur (ATMA),Maruploi Foundation, among others,is noteworthy. Their relentless struggles led to their victory in 2016, and I quote Randhoni of SAATHI Manipur from a short interview I did for this article:

Post Supreme Court NALSA verdict in 2014 transgender people in the state came out to assert their rights and advocate with the Judiciary for one to get the gender identity change document and with the Govt. of Manipur to establish a Transgender Welfare Board (TGWB) in the State. Their struggles had earned the support of civil society organizations. The board thus was established in August 2016, with Social Welfare Department as the Nodal Department and is one of the few in the country that has a Transgender men group as members of the Board. Having said, this we still need more commitment from the Govt. to implement the recommendations SC -NALSA judgment in its entirety and make the TGWB a fully functional one.

Supreme Court 2018 Verdict on Section 377 and its Impact in Manipur

It will be wrong to say that the LGBTQ movement in Manipur only intensified after the Supreme Court Verdict on Section 377 in September 2018, but it is also undeniable that the verdict opened new doors. There has been a surge in community mobilisation, digital activism and media representation. However, it doesn’t necessarily signify that society has suddenly accepted the struggle, as censorship, stigma, discrimination still prevail. People are still apprehensive talking or hearing about discourses on sexuality.We are at a very interesting albeit a complex time when the colonial law has been revoked, setting the tone for fiercer and more widespread LGBTQ activism in the state, yet people are still caught in a conundrum of political unrest and internal rifts. On the one hand, the marriage of two women some months ago enthralled the LGBTQ community both in Manipur and outside, and created quite a buzz on social media. The marriage sparked celebration besides criticism from some spheres. The glamour, splendour and extravaganza created a storm on social media; pretty photos to mention the least. On the other hand, earlier this year in February, according to the testimony of the survivor (a closeted gay man), he was hanging out one late evening in a deserted place; it turned into a gruesome incident. Three men assaulted him in the deserted Utrapat that falls under Nambol area. They dragged him into a Tata Tempo, knocked him down, took him to a thatched hut and violated him until a fisherman intervened. It is an irony that the LGBTQ movement fought for reading down IPC 377, and yet it is still the only key tool for a male rape survivor to prosecute his perpetrator. A case is still to be registered using IPC 377. As a close confidant to the survivor, family and the lawyer, I am looking at resources and approaches to proceed with domestic litigation and compensation. But without resources and networks, there is little one can do. Human rights and sexuality do intersect with class and privilege to say the least.

Conclusion

I would like to conclude my article by stating that if one is disappointed that there is so much in this article about socio-political and historical engagements and very little about sexuality and gender, then in my defense I must appeal that this is what Manipur truly is. In the pyramid or hierarchies of social issues, sexuality unfortunately lies lower down. I agree with Shanta Khurai, Founder of AMANA, when she said, “Gun power is much more powerful than sexuality.”

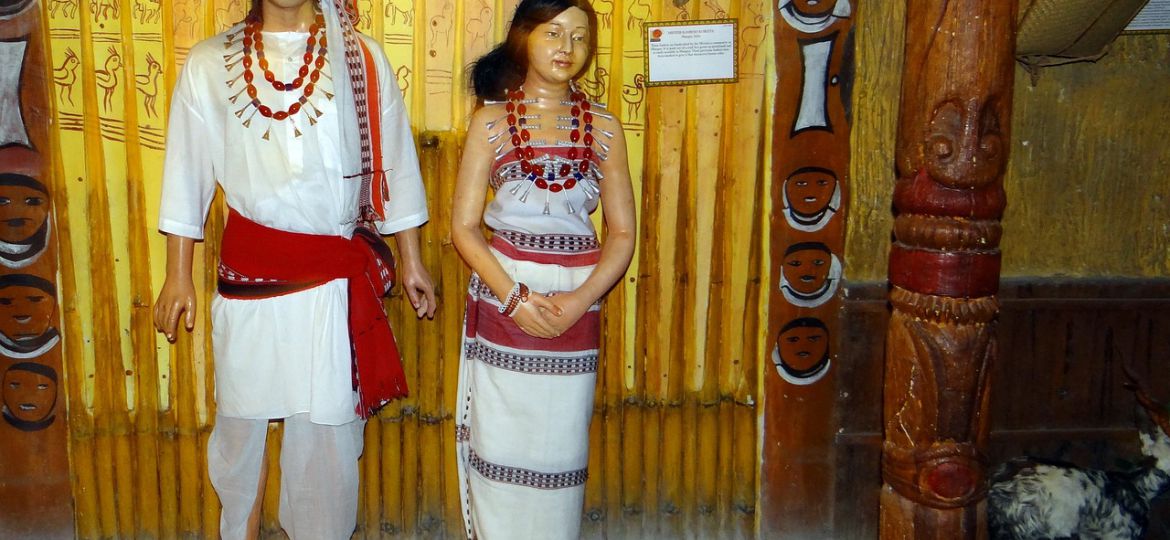

Cover Image: Pixabay