Dr. Reetika Revathy Subramanian is a Senior Research Associate at the School of Global Development, University of East Anglia, working on the IDRC/FCDO-funded Successful Intervention Pathways for Migration as Adaptation research project. She holds a PhD in Multidisciplinary Gender Studies from the University of Cambridge and has spent the past 15 years working as an ethnographer and journalist, with a focus on gender, labour migration, and climate adaptation. Reetika runs the Climate Brides project and podcast, which investigates how climate change is intensifying the drivers of child marriage in South Asia. She is also the co-author of Raindrop in the Drought: Godavari Dange, a multilingual comic book. In 2025, she was named a New Generation Thinker by the BBC and the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Shikha Aleya (SA): Reetika, thank you for taking out time and energy for this interview. In this issue of In Plainspeak, where we look at multiple connections between climate change and sexuality, we’d like to start with a question that helps us reboot. We need to understand some basics in an area that has become highly technical and, at the same time, related to the simplest daily actions, such as switching on a light. Reetika, when you focus upon climate change, what are the foremost thoughts, events, and human experiences that you would pin to the board first?

Reetika Revathy Subramanian (RRS): Many thanks, Shikha. It is a real pleasure to be in conversation, and to begin with a question that invites us to pause and look beyond the technical.

When I think about climate change, what comes to mind first is not datasets or models, but people. The everyday, often invisible, experiences of communities trying to make sense of a crisis that is no longer slow-moving or far away, but here, now, shaping their daily lives.

In the villages of western India, I have met girls pulled out of school, women shouldering the full burden of caregiving as men migrate for work, and households stretched thin through back-to-back droughts. In the Himalayas, I have seen landslides and fields washed away, and in their aftermath, women quietly rebuilding: sharing labour, forming collectives, growing food against all odds. And along the coasts of eastern India, I have spoken to fishing communities who now live in constant fear of cyclones, as rising seas and eroding shorelines threaten both homes and livelihoods. But these aren’t just rural realities. I grew up in Mumbai and have spent most of my adult life there. For a long time, climate change felt like a distant concept – something that happened elsewhere. But that distance has collapsed. Now, even in everyday conversations with my mother, who also grew up in the city, she talks about how the summers are harsher, how the rain comes all at once, how flooding feels deeper, more dangerous. Mumbai is seeing more frequent and intense heatwaves, coastal flooding, and extreme rainfall, all of which are being intensified by unplanned urban growth, the loss of green spaces, and poor drainage systems. These impacts fall hardest on low-income communities living in informal settlements along the city’s coastlines, creeks, and floodplains.

So when I think about what I would pin to the board first, it is these overlapping, intimate realities – rural and urban, spoken and unspoken. It is the girl walking miles for water, the mother in a high-rise apartment suddenly cut off because waterlogging has blocked access roads and made waterborne and vector-borne diseases a serious threat in her daily life, and the fisherfolk in coastal pockets who live with the constant threat of cyclones, losing not just their boats but entire seasons of livelihood. These stories remind us that climate change is not just environmental. It is social, political, economic, emotional. And it demands that we listen carefully to who is affected, how, and what they are already doing to survive.

SA: This helps us set a context that is easier to grasp. This Instagram post from Climate Brides, mentions ‘the institutions of early marriage, kinship, sexualities, and the environmental crisis. The links are complex, dynamic, and seemingly irrefutable’. In this context, when we look at human behaviours, and adapting, what are the key points of intersection that you see between climate change and sexuality?

RRS: Thanks for a very pertinent question. Climate Brides began in 2021 as a way to bring my doctoral research into the public domain. My fieldwork in Marathwada, western India, looked at early marriages that had become closely tied to labour migration, especially in the sugarcane belt. Years of drought, paired with the unbridled expansion of the sugarcane industry, gave rise to what locals sometimes call ‘gate-cane weddings’ – quick-fix, shortcut unions where young men and women, often barely acquainted, were married within 36 hours. These weren’t isolated events. Recruitment patterns in the sugarcane industry explicitly favoured husband-wife pairs. So while drought made it harder to find local livelihoods, marriage offered a gateway to income, with wives expected to work in the fields alongside their husbands. Over time, marriage became institutionalised not just as a social rite, but as a form of labour mobilisation and climate adaptation, one that transferred enormous physical and emotional burdens onto adolescent girls.

That is the context in which Climate Brides was born: first as a set of social media explainers, and later as a podcast to document stories and insights from across South Asia. We spoke with journalists, researchers, activists, and civil society workers – all grappling with the overlapping crises of climate stress and gender inequality. What became increasingly clear was this: climate change does not directly ‘cause’ early or forced marriage, but it absolutely amplifies the pressures that sustain them, whether it is economic insecurity, displacement, or the breakdown of support systems.

In numbers, South Asia is among the most climate-vulnerable regions globally. The World Bank estimates that nearly 750 million people (half the region’s population) have experienced one or more climate-related events since 2000. But what’s equally important is the nature of these risks. In coastal regions like Bangladesh or Balochistan, rapid-onset disasters such as cyclones and flash floods lead to immediate, often reactive decisions. In contrast, in drought-prone areas like Marathwada or parts of Afghanistan, slow-onset events create prolonged scarcity, which gradually reshape daily decisions around marriage, mobility, and survival.

One story that really stayed with me came from journalist Ruchi Kumar, who shared insights from internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in Afghanistan. There, families devastated by years of drought and economic collapse were marrying off daughters as young as nine in exchange for toyana, or bride price: livestock, money, grain. For many families, this wasn’t seen as exploitation, but as the only available form of protection.

In another episode, Professor Nitya Rao reflected on post-tsunami South India, where widowed men were paired with young women and girls from coastal villages – often under the guise of protection, or to access government schemes. These were not marriages in the traditional sense. They were stop-gap solutions in the absence of a functioning state.

So when we talk about the intersections between climate change and sexuality, we are really asking: who absorbs risk when crisis hits? And in many contexts, marriage becomes a mechanism of that absorption – one that is deeply gendered, classed, and caste-marked. We are not drawing a simple cause-and-effect line here. We are tracing a complicated web in which climate pressures interact with long-standing social hierarchies, often reinforcing them in subtle but significant ways.

SA: This next question begins with, and flows from, a question posed on your website for the podcast Climate Brides. What are the costs when girls are forced to carry the burden of survival? If we are to expand the notion of cost, how does that unfold? And, when we expand our perspective of gender, beyond the binary, to include marginalised gender identities, what is your understanding of how the social impact of climate change may be mitigated for such diverse communities?

RRS: This question really goes to the core of the work we are doing with Climate Brides. When girls are forced to carry the burden of survival, often through early or forced marriage, the costs are immense and layered. At one level, these are measurable: girls drop out of school, are pushed into unpaid caregiving roles, lose access to healthcare and reproductive rights. But when we expand the notion of ‘cost’, we begin to see what is harder to quantify – the erosion of agency, voice, and possibility. These costs are intimate, systemic, and intergenerational.

To help illustrate this complexity, we developed the Climate Brides Map which is a thematic, multilingual visual tool that connects the dots between climate risk and adolescent girls’ rights in South Asia. The map shows how reproductive health systems collapse in disaster-hit regions, how girls’ unpaid labour becomes invisible but indispensable, and how legal protections are eroded in moments of environmental stress. It also points to how conflict, migration, cultural norms, and lack of education converge to push girls into early marriages, often framed as a “necessary” adaptation.

The Climate Brides Map highlights how climate risks in South Asia intensify the structural drivers of child marriage, which is a critical yet often overlooked consequence of ecological stress. By mapping these connections, we aim to deepen understanding of how climate change disproportionately impacts women and girls, reinforcing existing vulnerabilities. The map and its accompanying explainers are being translated into multiple regional languages to support local use by educators, researchers, and community advocates working directly in affected areas.

This mapping effort is complemented by our podcast conversations, where we speak with activists, community organisers, academics, and frontline workers, each offering a different entry point into understanding how climate adaptation intersects with girls’ lives. Together, these platforms help challenge the narrative of resilience that is so often demanded of girls, and instead ask: What are the systems failing them? What are the alternatives they are building in response?

And while Climate Brides primarily centres the experiences of girls, we also recognise that climate change impacts diverse gender identities in differentiated ways though often with similar patterns of exclusion and invisibility. Any serious conversation must take these lived realities into account, and place justice, not just adaptation, at the centre of our response.

SA: “After years of trial and error, we finally built a model that combined the local climate patterns, with the women’s own social pressures.” This is a sentence from the comic book ‘Raindrop in the Drought: Godavari Dange’. I’m a fan of comics and this sentence struck me because I wondered if I can see or feel characters saying things like this in a comic book, and I find that I can. Please share your insights about creating and disseminating research-based communication such as this, how is it received, and what support does such communication need?

RRS: I am so glad that line struck you. That sentence (“After years of trial and error, we finally built a model that combined the local climate patterns, with the women’s own social pressures”) captures both the groundedness and the ambition of Raindrop in the Drought: Godavari Dange. It holds memory, method, and emotion all at once. And for Maitri Dore, my friend and co-author, and me, it was important that readers could hear Godavari in that moment: tired, persistent, and deeply proud.

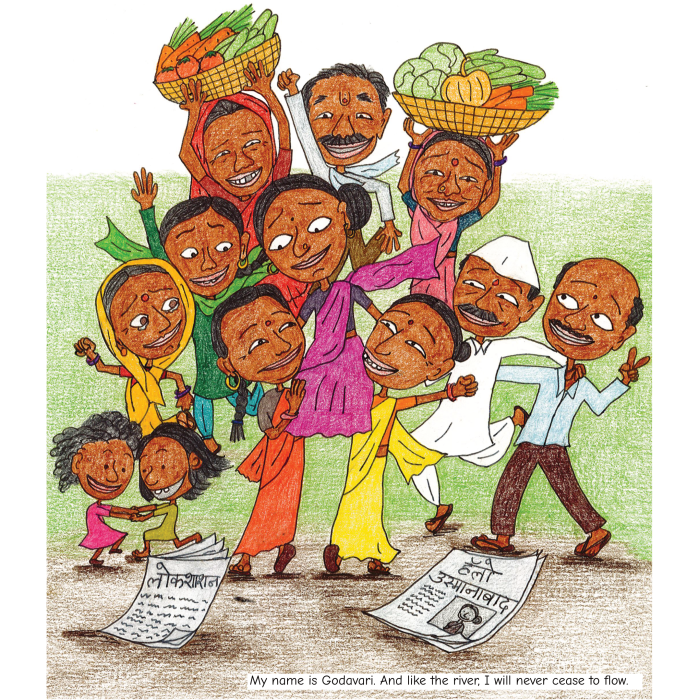

The comic traces the life and work of Godavari Dange, a farmer, widow, and feminist organiser from drought-hit Marathwada in Maharashtra. Despite deep personal loss, she went on to mobilise over 50,000 women, especially from Dalit and Adivasi communities, to take up sustainable farming on their own terms. The one-acre model she helped shape is not just an agricultural idea. It is a quiet, revolutionary act of climate adaptation, economic autonomy, and gender justice.

Raindrop in the Drought: Godavari Dange / Goethe-Institut

We created the comic as part of the Goethe-Institut’s Movements and Moments initiative, with the aim of centring grassroots feminist storytelling from the Global South. And honestly, it was one of the most humbling collaborations I have been part of. As city-based, upper-caste researchers, Maitri and I were constantly aware of our own position in the process. During our field visits, we recorded over 20 interviews with Godavari’s family, friends, colleagues, and collaborators, letting her words shape both the scope of the project and the way the story was told. Every sketch, line of dialogue, and translation was shared with her, often over WhatsApp, where she would send us photos, memories, voice notes, and feedback. Her voice shaped not just the content, but the feel of the book.

From the outset, we designed the comic to be multilingual, visually-led, and accessible. We used more artwork and minimal text to ensure that it could travel across literacy levels and local contexts. Dissemination was deeply local and community-driven. Swayam Shikshan Prayog (SSP), the grassroots organisation Godavari is affiliated with, helped circulate the comic across women’s collectives, government schools, and libraries in Osmanabad and beyond. The book also caught the attention of the local district administration, and has sparked conversations around land, farming, and gender at both community and policy levels. The comic book has since been translated into Marathi, Hindi, Urdu, Telugu, English, and German, and turned into a short film, with the narration voiced by Godavari herself through WhatsApp voice notes. The video has circulated widely via YouTube, WhatsApp, and local screenings. That intimacy, hearing her tell her own story in her own cadence, makes the film feel personal and powerful.

Some of the most meaningful responses have come from women farmers themselves, many of whom are non-literate. They have engaged with the visuals, recognised themselves in the frames, and shared the comic with their daughters. For us, that is a powerful indicator of what research-based storytelling can do; not just inform, but connect. Not just disseminate, but dignify.

Analytically, this kind of work challenges traditional hierarchies of knowledge. It asks us: who gets to narrate the story of climate adaptation? What does ‘impact’ look like when the audience isn’t other academics, but women in remote farming communities? Comics like Raindrop in the Drought complicate the binary between research and storytelling. They demonstrate that narrative, when crafted with care and collaboration, can hold nuance, data, emotion, and structure, all at once.

But such work requires more than good intentions. It needs long-term institutional support, not just to produce, but to translate, distribute, and sustain. We need funding that understands creative dissemination as part of research, not a postscript to it. And we need to make space for more collaborations between scholars, artists, activists, and communities, where every participant is treated as a knowledge-holder, not a subject.

Our hope is that Raindrop in the Drought continues to live many lives – in schools, village meetings, climate classrooms, and feminist archives. Because stories like Godavari’s remind us that adaptation is not just about coping with crises. It is about reclaiming power, reimagining land, and rewriting what survival looks like together.

SA: Thank you again Reetika! To end this interview with a cue to help progress this conversation – climate change is increasingly in the news and media, but it has not as yet become a part of familiar conversation. Which, to a great degree, is also true of conversations about sexuality, though the reasons vary. For those who are brave enough, and curious enough, to have these conversations in their lives, homes and workplaces, where does one begin?

RRS: Thank you, Shikha, and truly, thank you for the space you have created in this conversation. As you said, climate change and sexuality are increasingly present in media, policy, and activism, and yet, they often remain absent from everyday conversations. They are deeply personal, but also political. And that makes them hard to talk about, even when we are directly affected.

For those wanting to begin these conversations, a good starting point is simply to listen. These themes are already present in stories about unbearable heat, rising food costs, a daughter’s marriage, or navigating love and violence. Climate may not be named, but it often lingers in the background, shaping pressure points and possibilities. These effects don’t always erupt; they accumulate. Across a lifetime, climate stress can shift when people marry, migrate, or assert desire. Across generations, it can shape how love is expressed, how care is given, and what futures feel possible. Elders may carry memories of different climates and norms; younger people may face choices that feel narrower, more urgent. Our role is to surface these connections in order to build bridges between private experience and public systems, between what is felt and what is named. That is where new, necessary conversations can begin.

That is what we have been trying to do with Climate Brides. And it has not always been easy. One of the biggest challenges has been resisting the urge to oversimplify. Climate change is a threat multiplier as it intensifies existing vulnerabilities. But it is rarely the sole cause. If we attribute everything to climate, we risk depoliticising reality by erasing histories of caste, patriarchy, inequality, and state neglect.

As part of my ongoing research on climate migration in South Asia, I am contributing to a cross-country study in Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and India on how masculinities are being reshaped in times of crisis. Climate change is not only redrawing migration routes, it is rewriting the social contract of gender. We are speaking with men, long defined as providers and protectors, as they navigate economic precarity, disrupted family life, and shifting expectations – sometimes adapting with flexibility, sometimes responding with control. Through a masculinities lens, these narratives reveal a deeper story: one that links mental health, insecurity, gender-based violence, and the renegotiation of roles to a broader, relational understanding of gender under climate stress.

So the work, for me, is about holding complexity. Not looking for neat answers, but showing stories in all their layered, messy realities. And doing that while also acknowledging my own location of sitting in an international university and writing about communities back home. It is a gap I cannot ignore. It forces me to keep asking: whose story am I telling, and why? Who is it for?

Translation has been another space of learning and unlearning. Moving between academic language and lived experience, between English and regional languages, has shown me how meaning can get lost or imposed. Some of the most generous feedback has come from collaborators on the ground, pointing out what I missed, or where something did not land.

What these conversations need, and often lack, is support: not just safe spaces, but time, trust, pedagogy, funding. Whether through comics, podcasts, classrooms, or community meetings, we need to invest in ways that allow people to explore these themes with care and context.

If there is one thing I have learned, it is this: we do not need all the language or answers to begin. We just need to stay present, stay humble, and listen, especially to those already doing the work, even if they don’t call it that. That is where real conversations begin.

Cover image by Chris Lacey