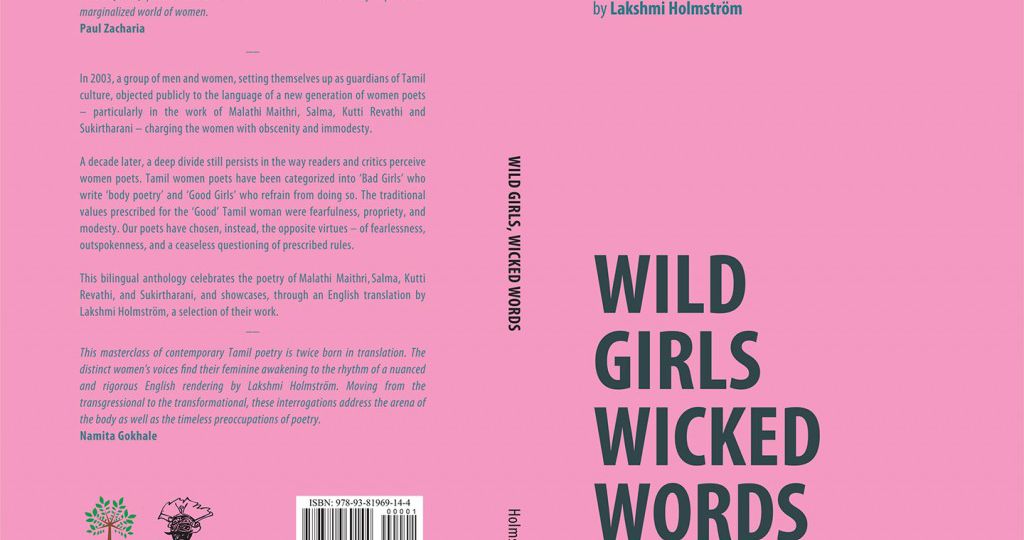

The collection Wild Girls, Wicked Words is an anthology of poetry translated from Tamil by Lakshmi Holmstrom. The collection contains the work of four contemporary women poets Malathi Maithri, Salma, Kutti Revathi and Sukirthani. In the preface, Holmstrom mentions that these poets came into prominence in the early 2000s when there was a rise of Tamil ethnic chauvinism.

Holmstrom notes that charges of obscenity were levied on women lyricists for writing explicitly about female desire and sexuality. In the male dominated cultural world of Tamil Nadu in which desire is always scripted from a male point of view, these charges are common. For a Tamilian who has little or no literary inclinations, Tamil cinema provides the only platform through which one can experience poetry in everyday life. More often than not, these movie lyrics are often punctuated with strong misogyny in which women are depicted as manipulative lovers who are responsible for the ruin of men. In addition, the Dravidian parties that have ruled Tamil Nadu from independence have crafted a strong cultural pride in the literary figures such as Kannagi who embodies the ‘true’ Tamil ideals of the model Tamil woman namely loyalty, virtuousness and selflessness.

In this context, any poetry that speaks of the experience of the Tamil woman through the idioms of the body, sexual desire and domesticity is immediately viewed as a transgressive and immodest expression that is unbecoming of Tamil identity. It is for this reason that this collection is an important one as it brings together four women poets who are from diverse and underprivileged backgrounds.

Of the four poets featured in this anthology, Malathi Maithri and Sukirthani have not had easy access to formal education because of the castes they were born into. Taken together, these poets speak of the everyday lives of women who are discriminated against because of their caste identities. In their poems, the poets speak of the difficulties of forging a space in which these experiences can be inscribed. In Tamil cultural registers, relationships to individual and collective rootedness are always theorized by spatial markers and allusions to mann, the soil.

Tholkappiyam, the oldest treatise on Tamil grammar from the Sangam corpus, divides the subject matter of literature into two spatial categories: akam (literally meaning inside but used for poetry with themes of love) and puram (outside; poetry with themes of war). In Tamil cultural consciousness, spatial markers are key points through which personal and group identities are mediated. Thinai is a theorization derived from the earliest Tamil grammar treatise Tholkappiyam and the term denotes a theoretical register that comprehensively maps out the cultural and social worlds of Tamil regions. Tholkappiyam has five thinais for the akam classification: Kurunchi (mountains and surrounding areas), Mullai (forests), Marutham (agricultural lands), Paalai (deserts), and Neythal (sea and coastal landscape). Each thinai has a characteristic flower, a landscape, time, season, music, bird, a beast, tree or plant, water (rivers, ponds etc), occupation, deities and people.

Malathi Maithri in her evocative poem ‘My Home‘ describes the alienation of living in a caste ridden and patriarchal society by proclaiming that the traditional Tamil spatial markers do not provide her with the room to voice her experiences. Her poetry is filled with the need to craft spaces for the contemporary Tamil woman. For Malathi Maithri, poetry provides the contours through which this space can be created through a revisioning of traditional markers of femininity and poetic language. For instance, in another poem titled ‘Demon Language’, she says,

“Demon language is poetry..

poetry’s features are all saint

become woman

become poet

become demon”

With this poem, with an indirect allusion to the legendary Tamil woman saint Karaikal Ammaiyar, Malathi Maithri calls for a new idiom of femininity, which contains outspokenness and fearlessness to break down the barriers of chauvinism associated with Tamil culture.

The struggle to find a new language to capture contemporary experiences of women is a trope that runs through the collection. Sukirthani, who hails from a Dalit Paraichi background says that she strives to find a fresh “infant language which is still afloat in the womb”. Her poetry is filled with the voices of Dalit women and their experiences of caste discrimination. In her poetry, she questions the hypocrisy of caste practices by inscribing her identity. She says,

“I speak up bluntly

I am a Paraichi”

While it would be shortsighted to classify her entire oeuvre of poetry under the label of Dalit poetry, the theme of resistance against oppression emerges in her poetry through the choice of subjects such as the Sri Lankan ethnic war. In the poems that talk about the war, Sukirthani combines the experiences of the personal, domestic space with the political and public space of the contested homeland of Eelam. Switching between voices of the mother, wife and lover, these poems question the logic behind the violence of war.

In Salma’s poetry, experiences of domesticity take primary importance. Her poetry addresses the claustrophobia of arranged marriages where the loneliness experienced by the woman is detailed. Salma’s poetry explores the tiresomeness of living through a loveless marriage in which there is little communication between the couple. Salma’s imagery relies on a fresh perspective of domestic images, which deftly captures feelings of entrapment. In the poem An evening, another evening, Salma writes that her

“.. present is as tangled

As the world of a cat that lurks in the kitchen”

Her poetry is marked by a search for solitude that can be teased out through this loneliness. Her solitude takes on the images of the surreal through the figure of a tiger in her bedside and painted houses that offer her a space to voice her desires and hopes.

While all the four poets in the anthology speak openly about female desire and the body, Kutti Revathi’s poetry uses the framework of the erotic and the body more extensively and provocatively to question patriarchal norms. Her most famous poem ‘Breasts’ which form a part of the poetry collection Mulaigal (Breasts) boldly speaks about the female body, which has traditionally been framed as an object of male desire. Her other poems frame the landscape and the seasons within the contours of the female body and with inter-textual allusions to desire that permeate the love poetry of the Sangam period. In the poem Rain river, Kutti Revathi writes that the “force of our love/is like red earth and pouring rain.”

This bilingual edition occupies an important place in Tamil literature available in translation. By speaking of the contemporary experiences of Tamil women, these poets have given a voice to emotions that were rarely acknowledged in Tamil poetry.