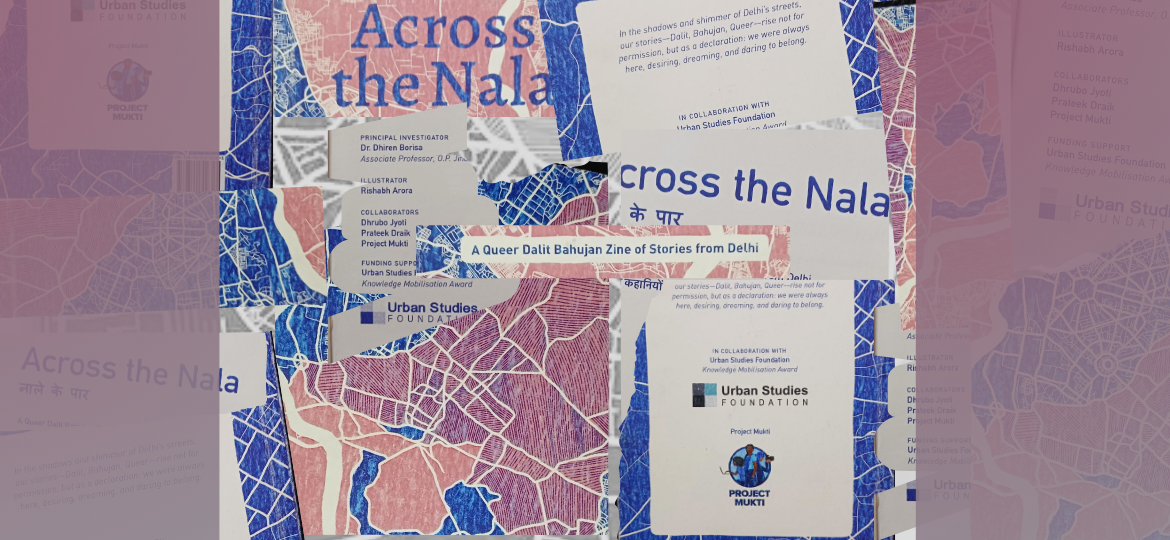

Born out of a story-telling and zine-making workshop, Across the Nala (2025) poignantly explores Dalit queer people’s affective relationship to the city of Delhi. At the heart of this pastiche of moving stories and artworks lies the unasked question: what does it mean to hold on to a city without having anything to hold on to?

When I first read the zine, published by Dhiren Borisa in collaboration with the Urban Studies Foundation and Project Mukti, I realised that it was not merely a despondent story about caste-based alienation in an urban city. Something else – an inconsolable and incomprehensible feeling – kept clutching at me, like an unidentifiable wound, somewhere on the inside. I could not accurately translate its enduring effect; however, it felt persistent. Like someone – or something – that refuses to let go. Of what, I still don’t know. I thought about this uncertainty and realised that perhaps it is what is being held on to, in me and in the stories of the zine: an attachment to uncertainty, and the possibilities that can open up.

Our everyday idea of “holding on” is often transitive. We “hold on” to hold an object, and to possess and own it. Across the Nala, however, proposes a different grammar of attachment – one shaped not by possession of but rather camaraderie with the object. An unpossessive attachment to something, and by that virtue, an openness to other attachments. A holding on without imprisoning what is being held.

Holding on Without Holding on to Something

It was then that my eyes fell on Dhiren Borisa’s introduction, directed almost as if by desire, where I read about the zine’s foundations: “queer acts, queer objects, and memory” (p. 1). The omission of the adjective “queer” from memory made me wonder why it did not need that qualification. And consequently, why “acts” and “objects” needed it. Memory is often considered an unreliable source of history because it is driven by desire. It bears no straightforward chronology, seems muddled with personal tangential associations, and rarely gives us any concrete evidence to hold on to history. By nature, memory seems queer at its heart for its deviancy and promiscuity. This is why acts and objects need to be queered up to align with it. A queerness that insists on desirous unreliability, and an unreliable desire that can provide nothing permanent or concrete.

The queer acts, objects, and memories of Dalit queer folks in Across the Nala thus hold on to the city not by way of possession or need, but through the ephemeral thread of desire – one that does not wrap itself around an object, but rather dissolves and diffuses around it. Unlike possessive attachments that demand a sticky and authoritative relationship, especially in an urban city where belonging is recognised by social, legal, and cultural forms of ownership of land, property, and capital, the stories of Across the Nala rewrite those narratives of belonging in a different grammar altogether. They propose that to belong to an urban city you do not need to possess or conquer land. You can make a belonging out of ephemeral objects, desires, and memories. Associations and relations that are not dependent on possession.

Queerness Against Caste

These queer attachments of Across the Nala critique caste at the epidermal level of everyday affect. As an ideology, caste advocates rigidity and purity and prides itself on owning a surname, identity, and property. As opposed to that, Borisa asks, “How do we engage with this withholding as a rich text of queerness without doing the violence that comes as temptation of an expose?”(p.1) Instead of holding on to identities with pride, Borisa asks us to explore the rich texture of queerness in withholding them. For many Dalit queers, withholding identity becomes the only way to access an urban city that otherwise insists on flamboyant possession and exposition of wealth, capital, and caste. As Jatin, one of the contributors, writes, “When I moved to South Delhi for work, my journey of hiding my locations began. That hiding was the only way I could be queer, and I really wanted to embrace this queerness fully” (Borisa, 2025, p. 12). As both Borisa and Jatin show, withholding paves the path to a rich texture of queerness and desire that was otherwise prohibited by caste-based deprivation. This act of holding away information, or engaging in secrecy, especially of identity, betrays an act of disrobing oneself of one’s own self. Jatin reveals the paradox of desiring queerness: the only way to “be” queer – to “embrace it fully” – means not to “be” anything at all. To access the desirous place of queerness, one must hold back identity – one’s primary/ ultimate possession. Mobility in caste society, thus, becomes possible through this “act” of queerness in which one stops holding on to their given identity, and practises a form of holding back to dispossess oneself of it. This queer form of anti-caste attachment insists on holding by way of holding back – that is, by not-possessing identities.

If mobility is made possible by this queer anti-caste attachment, then it debunks the popular misnomer that caste only prohibits the mobility of lower caste people. Neeraj, another collaborator of the zine, shows that while for the lower castes, the prohibition of mobility remains external; for the upper castes, it remains internal. While handing out rejection, an upper caste lover tells him, “You never told me you live in Raghubir Nagar, because if you would have told me that you live in Raghubir Nagar, I would have never dated you” (Borisa, 2025, p. 6). The disclosure of Neeraj’s location leads him to retrospectively draw impermeable borders between them. Had Neeraj told him that they live in “Raghubir Nagar” (a location in Delhi that bears associations with lower caste people), then the lover “would have never dated” them. Geographical location, and contingently, caste location – and not the usual looks and behaviours – become the negotiating parameters of desire here. Caste mandates one not to defect their social and geographical positions. A possessive attachment to one’s identity, a firm holding on to it, like caste, holds one back from moving out of it.

Nadi aur Nala (River and Drain)

The title of the zine, Across the Nala, is the primary site where this affective drama of attachments play out most strikingly. It brings out a host of idiosyncratic phrases associated with rivers that have much purchase in the subcontinent, from tropes that consider the journey across the Ganges a journey towards salvation, to idioms that capture a syncretic ethos like Ganga-Jamuna Tehzeeb (the culture of Ganga and Yamuna). Almost all of these phrases associated with the crossing or the confluence of rivers carry novel significance. Across the Nala (a drain), then, exists in ironic contrast to such tropes and metaphors. If the rivers (Nadis) signify novelty and positivity, then a Nala (drain) suggests – true to its name – that which carries the outflowing waste and negativity of a culture. In centring the conversation around the Nala, Borisa makes us confront and grapple with the aspects of a society that we cast out, discard, and throw away. By forcing us to look at the other side of this narrative of novelty, Across the Nala queers our gaze. It forces us to pay attention to that which is left behind when one holds tightly to something.

Borisa tells us that the Nala in the title refers to Sahibi, a tributary of the Yamuna that cuts through the heart of Delhi. While a tributary is a part of the river, Sahibi becomes a drain, its opposite. And people who live near the “stench” of Sahibi acquire the “shameful associations of caste.” To hold on to its novelty and purity, Yamuna dissociates with Sahibi; South Delhi separates itself from people who live across the Sahibi Nala, and upper castes marginalise and exclude lower castes from society to maintain their status. The undergirding anxiety of these rigid caste-like attachments lies in this: to possess and preserve one’s purity and identity, one assiduously needs to dissociate oneself from one’s inherently shameful and negative parts. The logic of purity requires first that you vehemently separate the impure from yourself in order to then fabricate a retrospective image of the pure. Alternatively, one can say that one holds on to objects possessively because they realise it is not theirs to have in the first place, and they fear they will lose it once they loosen their grip. Unlike queer attachments that are unafraid of promiscuity and ephemerality, caste attachments guard themselves by maintaining their fixity and rigidity. They make a tight fist because they are scared to hold a stray finger and be led astray in its company.

Across the Nala does the unique work of helping us think about caste not simply as an identity, or a sociological condition, but also as a form of attachment, while also providing its antidote in the name of queerness: an invitation to “hold on” to things without wanting to hold them or be held by them forever.

References:

- Borisa, D. (2025) Across the Nala: A Queer Dalit Bahujan Zine of Stories from Delhi.