Undoubtedly, LGBTQ+ literature and writing in India has witnessed an ‘explosion’ in the past two decades, and the trends in contemporary publication promise consistent growth in the future too. However, issues of queer representation in existing literature, and especially contemporary literature, need to be continually invested in, for literature is a key marker of society’s outlook on and reception of such sensitive subjects as homosexuality and ‘queer’-ness. Given the contemporary socio-cultural and politico-legal discourses concerning how and why the ‘queer’ must be accorded recognition, dignity, and rights, one rising sub-genre of queer literature that needs adequate and further investment is the ‘gay romance’ fiction being published in India. In the English language, novels like R. Raj Rao’s The Boyfriend (2003) and Hostel Room 131 (2010), Mayur Patel’s Vivek and I (2010), Janice Pariat’s Seahorse (2014), Vicky Arora’s Terminal Love (2016), Aakash Mehrotra’s The Other Guy (2017), Sheryn Munir’s Falling Into Place (2018), Bhaavna Arora’s Love Bi The Way (2016), Saikat Majumdar’s The Scent of God (2019), etc., are a few examples of how ‘gay romance’ has become an emergent and promising phenomenon in the Indian literary scene concerning issues of non-heteronormative sexualities and queerness. They also stand as critiques of the existing and continued lack of focus on and side-lining of queer sexuality and the discourses on desire, eroticism, and love in the literary ‘mainstream’ that I will discuss with respect to a couple of examples.

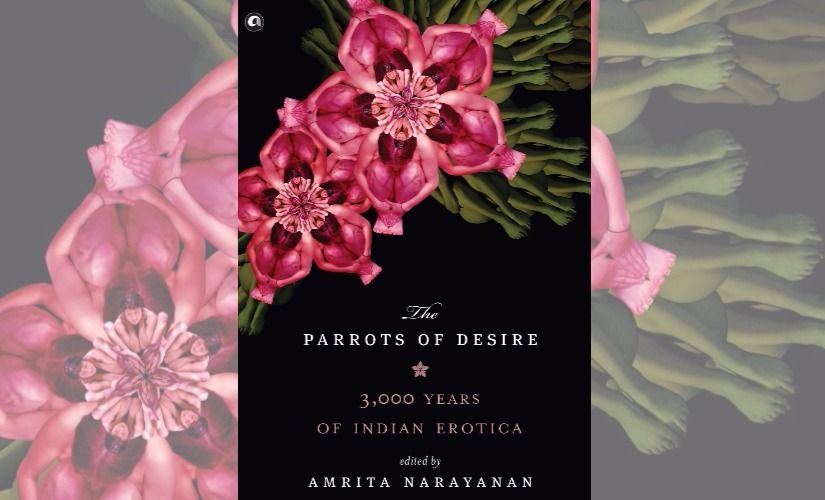

The Penguin Book of Classical Indian Love Stories and Lyrics (1996), edited by Ruskin Bond, makes a distinction between the ‘literature of love’ and the ‘literature of love-making.’ In the ‘Introduction,’ Bond states that he has not included extracts from Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra as the art of love-making “does not really fall in the purview of this collection.”[1] This logic of sanitising the ‘love story’ from its sexual eroticism seems to be an implicit commentary on mainstreaming propriety and in the process, also seems to be inconsistent with ‘Indian’ traditions of the union between love and eroticism, especially in the context of same-sex desires, erotic love, and union that the Kamasutra describes (‘auparishtaka’ or ‘mouth congress’ discusses acts of oral sex vis-à-vis men who desire other men) without derision or censorship.[2] Historian William M. Reddy, in his study of the histories of ‘romantic love,’ claims that nowhere in the Indian context do “the conceptions, practices, or rituals surrounding sexual partnerships rely on an opposition between true love, on the one hand, and desire, on the other.”[3] He notes that in 8th-12th century Bengal and Orissa, erotic arousal and bodily sexual acts were not considered antagonistic to romantic love,[4] making Bond’s argument want revision. In its lukewarm ‘traditionalist’ approach that side-lines the erotic and the non-heteronormative, the anthology stands in stark comparison to the cultural beliefs and past traditions of the ‘literary romantics,’ as, contrastingly, Amrita Narayan presents in her anthology The Parrots of Desire: 3,000 Years of Indian Erotica (2017) being those who have been erotically positive and who believe in the legitimacy and agency of the erotic and the non-heteronormative.[5] I notice that similarly, contemporary writers of ‘gay romance’ fiction in India have challenged both the implicit politics of erotic propriety (while preserving the idea of the emotional-spiritual ‘romance’) and the explicit politics of non-heteronormative exclusion (while accepting the reality of plurality in ‘queer’-ness) in/of ‘mainstream’ texts of ‘Indian’ love stories. The few examples that I have mentioned earlier have brought same-sex love into the domain of romance fiction and most have done so rather audaciously with intense and elaborate depictions of both the sexual-erotic and the emotional-sensual, especially in their portrayal of loss and longing.

In his introduction to Indian Love Stories (1999), a collection similar to Bond’s in its non-inclusion of the romances of non-heteronormative sexualities, editor Sudhir Kakar makes the claim (about contemporary Indian writing on love and romance) that the “traditional certainty that a literary depiction of love is marked by the presence of the shringara rasa[6] is no longer available to us.”[7] The Natyashastra states that the shringara rasa or the erotic sentiment has its basis in sambhoga (union) as well as vipralambha (separation)[8] and that vipralambha “relates to a condition of retaining optimism arising out of yearning and anxiety.”[9] As such, Kakar’s second claim that the element of vipralambha no longer “heighten[s] love […] but only our despair”[10] marks a major shift away from the classical Indian ideas of romance and its performative aspects in literary traditions. However, this does not seem to be the case in the context of the contemporary ‘gay romance’ fiction that makes use of the ‘classical’ idea of vipralambha, rather diligently, by including positive denouements and happy reunions in the romantic plot, albeit in the context of non-heteronormative forms of loves and their expressions. Hinting at a politics of cultural hybridisation of literary traditions, several of the texts present both the shringara rasa and vipralambha as crucial in the heightening of the pleasures of love. For example, in Vivek and I, Kaushik often indulges in a ritualistic shringara where he partakes in grooming himself in order to impress his beloved Vivek and in the hope to lure him, with his beauty, into a sexual union. The Boyfriend makes a more agential use of the shringara rasa in the preparations leading to the ritualistic enactment of the marriage between the two male protagonists. In the context of love-in-separation, vipralambha features predominantly in Vivek and I as a positive element contributing to the romance plot. Whenever Vivek is away from Kaushik, the latter frets and longs for his beloved more intensely and passionately, making his desires grow stronger and his love deeper to the extent that Kaushik undertakes a risky journey to Vivek’s home in a far off village in the middle of the night for the sake of love. Similarly, Hostel Room 131 amplifies the element of love-in-separation by beginning the novel with an elaborate episode of the performance of vipralambha and in the form of Siddharth’s intense longing for and desperate attempts at reuniting with his beloved Sudhir. In fact, much of the romance plot includes the elements of numerous partings, ensuing love-in-separation, arduous travails and sensational reunions with an ultimate ‘happy ending’ to the love story. In these contexts of the love-in-separation in the novels, unlike Kakar’s observation regarding contemporary heterosexual romance fiction in India, ‘gay romance’ fiction re-presents separation as sustaining optimism and heightening love, making clear connections to the classical ‘Indian’ ideas of love and romance in positive terms of reclaiming tradition, challenging the mainstream (hetero-)canon of love, desire, and eroticism in the process.

[1] Ruskin Bond, ed., The Penguin Book of Classical Indian Love Stories and Lyrics (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1996), xii.

[2] See The Kamasutra of Vatsyayana, trans. Richard F. Burton and intro. Margot Anand (New York: The Modern Library, 2002), 66—74. For a discussion of the portrayal of desire in the Kamasutra, see Madhavi Menon, Infinite Variety: A History of Desire in India (New Delhi: Speaking Tiger, 2018).

[3] Reddy, William M. The Making of Romantic Love: Longing and Sexuality in Europe, South Asia, and Japan, 900–1200 CE (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 2.

[5] See Amrita Narayan, ed., The Parrots of Desire: 3,000 Years of Indian Erotica (New Delhi: Aleph Book Company, 2017), 1.

[6] The Natyashastra lays down the basic tenets of the art of drama and theatrical performance. As a crucial part of the treatise, the theory of Bhava-Rasa establishes a relationship between the performer and the spectator. Bhavas are the emotions represented in the performance, while the rasa, or the sentiment, results from the bhava or the state. See The Natyasastra: A Treatise on Hindu Dramaturgy and Histrionics: Ascribed to Bharata-Muni Vol I. (Chapters I-XXVII), trans. Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1951), 105—106. Rati – the state of love – is one of the eight permanent bhavas, and the rasa that it evokes is shringara – the erotic romance/love. For a discussion on the important status of the shringara rasa as conceived in literature as erotic love, see Ingalls, “Introduction,” 17—18.

[7] Sudhir Kakar, ed., Indian Love Stories, (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2006), 11.

[8] See Daniel H. H. Ingalls, “Introduction,” in The Dhvanyaloka of Anandavardhana with the Locana of Abhinavagupta, trans. Daniel H. H. Ingalls, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, and M. V. Patwardhan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 108.

Cover Image: Amazon