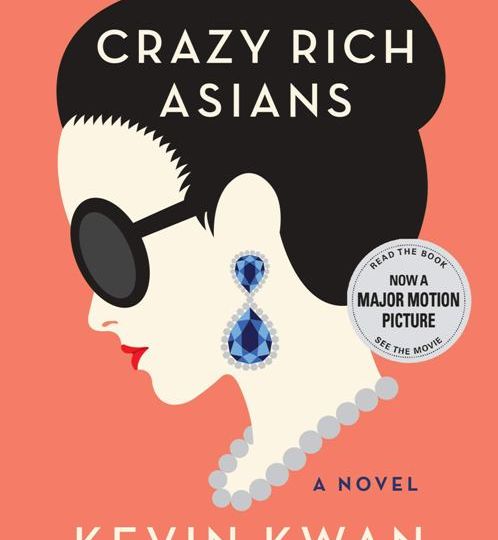

Crazy Rich Asians, a 2013 novel written by Kevin Kwan, became an international bestseller. The book inspired a Hollywood blockbuster film with the same title. The film was hailed as a milestone in the representation of Asian people in Hollywood.

Crazy Rich Asians chronicles the fantastically rich and decadent lives of tycoons in Singapore. The protagonists – Rachel Chu and Nicholas Young (Nick) – travel to Singapore to attend Nick’s best friend’s (Colin Khoo) wedding, for which he is the best man. Colin is to marry Araminta Lee. The union is to bring together two of the richest families in Singapore. It is a significant social event, and the wedding is to be attended by other rich families, foreign dignitaries, members of various royal families from around the world, and celebrities. Nick brings his girlfriend along to give her the opportunity to visit South East Asia. Nick is a member of the Young, T’Sien and Shang clan who all descended from Shang Loong Ma – who made a fortune – and Wang Lan Yin. The clan is spread out across the world – Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland and The United Kingdom.

The story is explicit and implicit in suggesting that heterosexuality is compulsory, and also ‘right’. It sets out a world in which marriages are arranged to ensure that the names of families are perpetuated – the family name is of utmost importance, and one can do anything to maintain its sanctity.

Maintaining the order of families and names comes at a price. Most important is to ensure that gender operates within a strict binary. The men’s scripts are distinctly separate from the women’s. The men are aggressive and virile pursuers of women; women are adept at being pursued, and play a hard game to make sure the men are interested, and do not let up until they are assured of marriage.

Lessons of heterosexuality are learnt young in Crazy Rich Asians. A 12-year-old Eddie Cheng, cousin of Nicholas Young, states, while playing a make-believe game,that his cousin the 10-year-old Astrid is to be his secretary because she is a girl. Her duties include massaging his shoulders and buying jewellery for all his mistresses. Eddie has learnt this from his best friend’s father – the third richest man in Hong Kong. Another example is when Mr. Goh – who is the father of Rachel’s Singaporean friend Peik Yin – is chided by his old friend Dr. Gu as having been “castrated” by his wife for not having a mistress. Mr. Goh and Peik Yin make a visit to Dr. Gu to enquire about the history of the Young family which Rachel may be marrying into.

Michael Teo marries into the Young family. He is the middle class husband of the very rich Astrid Leong. Michael is described as having an almost feral quality about him, and is the perfect specimen of masculinity. “Guys who looked like [him] obviously did not have to work hard to impress a woman,” say young men vying for Astrid’s attention. He gets to marry Astrid – who young men refer to as Goddess, and is the “chief object of [boys’] masturbatory fantasies,” Kevin Kwan explains.Their marriage is an unhappy one, but Astrid works hard to make sure it works while Michael schemes to escape it.

Almost all the young female characters in Crazy Rich Asians – except Rachel Chu, who is clearly the outsider – are groomed from an early age to be positioned in circles in which they will be the girl of choice for the right rich young man looking for a wife. Araminta Lee, the daughter of wealthy hotel owners Peter and Annabel Lee, gets to marry Colin Khoo (scion of one of the richest families in Singapore) because her parents made sure she attended the right schools and mixed with the right crowd, and even attended the right church so that she would be considered desirable enough for a family liked the esteemed Khoo’s to be considered as their daughter-in-law.

Araminta’s fiancé, Colin Khoo, laments to his best friend Nick Young about feeling trapped and not having a choice. He suffers from a severe anxiety disorder and crippling depression. His marriage was planned by his parents to ensure that the two rich families come together to increase their fortunes and strengthen their business connection. “It’s a good thing I actually want to marry Araminta,” Colin confesses to Nick. The reader is meant to understand that the matter of the two young people actually liking – let alone loving – each other is not important in these situations. Family fortune and connections come first. The children’s duty is to ensure that the family line remains intact, and the fortune grows. This is where the protagonists challenge the norm.

Nick Young’s arrival in Singapore with a girl (Rachel) sets tongues wagging. Rachel’s mother has already imagined that Nick would propose to her during the holiday. That must be the reason he is taking her to meet his family, she says. Actually, marriage was never on Nick’s mind until the day of his best friend’s wedding.

Nick’s family – especially his mother and the matriarch grandmother – fear that Nick is going to marry this girl whose family no one knows anything about. Nick’s mother sets up an elaborate plan to humiliate Rachel so that Nick will see her for the gold-digger that she assumes that Rachel is. She enlists her friends – more wealthy wives – as her co-conspirators in the effort. Nick is to marry, and must do so. But only to the woman who is of the right family and lineage.

Nick’s parents – Eleanor and Philip – live apart. Philip spends his days in Sydney returning to Singapore only when and if necessary. Eleanor lives in Singapore, but is hardly home. Kwan never explains why they live apart, but allows Nick to insinuate that his parents live separately because his father could not bear to be close to Nick’s grandmother. She is controlling, cunning and manipulative in an effort to make sure everyone in her family stays in line.

Upon hearing of Rachel, the mothers of eligible young women make sure their daughters are in Nick’s line of sight. They are encouraged to do what is necessary to get Rachel out of the picture. The young women gossip and lie and flirt all they can to try and steal Nick’s attention. The feminine tropes all come into play, and it does not look pretty. The make-up and designer clothes – which Kevin Kwan painstakingly highlights in detail – all serve to hide the ugly jealousy and covetous resentment just under the surface of these characters.

Kevin Kwan’s characters all fall into line and obediently follow social rules. They never question the gender binary in which they struggle. Ideal marriages struggle because the aim of the people in them is to be seen by the right people in the right places, rather than to build a safe and happy life for and with each other; the characters are lonely; there are mental health issues. Every character closely follows, much to their detriment, the gender scripts forced upon them. Those that oppose these scripts, suffer the consequences. Michael Teo faces constant humiliation from his wife’s family because he does not make as much money as her.

The writer also ensures all the characters are heterosexual. They must all be connected with someone of the other sex. Any interest from someone of the same sex can only be envy or jealousy. Nick’s good looks and intelligence are never the object of men’s desires. Astrid Leong is clearly the object of men’s sexual desires. Her exquisite taste in fashion is the object of women’s unattainable desires.

Kwan makes these gender distinctions because they are the order in which this society works. The growing of wealth is granted to heterosexuals. Their marrying into the right family secures their position in the will. Social punishments are swift and merciless. People are written out of wills on a whim. Heterosexuality here is not a choice. It is forced onto characters. It is done insidiously yet forcefully.

Perhaps Kwan’s characters were also cognisant of the strict laws in Singapore that forbid same sex relationships. Section 377 of the Singapore Penal Code criminalises sex between consenting adults of the same sex. The Singaporean government has been vehement against the repeal of Section 377. The prospect of being punished for being anything other than heterosexual may have influenced the choice of Kwan’s characters in choosing whom they love and marry.

Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians does not just highlight the lifestyle of the segment of Singaporean society that is unimaginable and unattainable to most people, it amplifies that heterosexuality is often not a choice. It is forced onto many people through means not too different from that experienced by the Crazy Rich Asians. While most people’s lives are not influenced by the tycoon and billionaire standards of the Crazy Rich Asians, societal and family expectations, gender scripts, social class, education and a whole myriad of other factors determine that someone identifies as heterosexual.