I have great respect for Michel Foucault and his views on sexuality in our present era. While speaking on the subject we inevitably engage in a modernist and yet anachronistic notion of a repressive past. Foucault challenges this idea, turns these arguments around and questions our present understanding of the issue. Human Sexuality and Sexuality Education has become a contentious issue. On the one hand there are fears of this leading to sexual promiscuity and experimentation, on the other hand we are concerned about teaching young people about their bodies and doing away with taboos.

Both sides of this argument are a part of our present and both are a product of our modern history. In the wake of Section 377 one can see clear fault lines in Indian society. Easy dichotomies – traditional or modern, oriental or western – have taken the place of the actual debate. In his work on sexuality, Foucault uncovers and analyses debates and finds conversations about sexuality in the apparently prudish Victorian era. Similarly while it seems like sex is hardly discussed in India, one will discover that sex is really everywhere: on our television screens, on our billboards, in every magazine, in our songs. We are not silent about sex; we are only silent on the conversations over sex. But with all the noise, one wonders why we are being so prudish about Sexuality Education? This is very similar to the silence Foucault is alluding to in his writing: furtive discussions, the ‘pathologising’ of anomaly. In that sense, we have not become more liberated, only just more regimented in our understanding of Human Sexuality. What is missing in these debates is a more nuanced and less hetero normative understanding of the issue. Sexuality Education is therefore not innocently omitted as much as it is silenced by resistance to intellectualism, to alternatives, to dispelling myths, to breaking taboos.

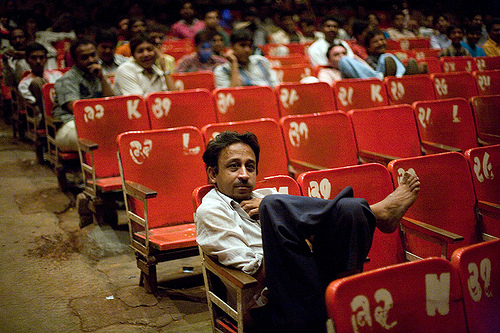

A few years ago I was talking to my professor about the difficulties ‘The Girl With a Dragon Tattoo’ met with when it was being released in India. The film is graphic and brutal in its portrayal of violence against women. However it is not sympathetic to the perpetrators; it transforms the victim into a vengeful person who has a strong sense of self preservation. My professor was surprised at how numerous item numbers (song and dance routines that are explicit in their content) were released with almost no rating, disseminated through television and radio but this film wasn’t. And yet, rape is a commonly used trope in Indian films. Arundhati Roy has written an excellent piece titled ‘The Great Indian Rape Trick’ addressing the subject. Amidst these obvious contradictions, Indian society does not come across as the prudish society it claims to be. Steve Derné, whose research is based on male cinema going audiences in India notes how the silences on the subject in educational institutions and families have led to alternative sources of information about sexuality, namely cinema, being created. His research is primarily based on Hindi cinema (Bollywood) and how it has become an outlet and ‘scopophilic’ tool in the hands of the Indian male film goers. Bollywood cinema is very particular about the way it approaches sexuality: it emphasises heterosexuality and rigid gender roles.

Similarly, media representations have legitimised certain kinds of bodies and sexualities. However there are problems in the way this legitimisation works. A case in point is how the national feminine ideal – fair, slim and able bodied – is seen as desirable. This has led to a new wave of cosmetic enhancements that reinforce the idea of what bodies are meant to look like in order to be desirable.

While the numerous television shows and films that are misogynistic and openly exploitative of women’s sexuality are perceived as ‘Indian’ and even family friendly, Sexuality Education in schools and universities, is met with resistance. We claim that this is a western and elitist idea that will spoil our children and expose them to concepts not meant for them. ‘The West’ and ‘modernity’ are used as deciding factors against any new idea. Suspended between ‘nativism’ and ‘westernism’ is a nation that is uncomfortable about addressing issues that distress it. On the one hand we have internalised the prudishness of our colonizers, and on the other hand we seem to seek a modern idea of sexuality within ‘our’ history. What really needs attention is the content of Sexuality Education and not its origins. Similarly the argument for and against legalising homosexuality has begun to rest on its ‘Western’ origins trapping LGBT people in India in a debate between western and traditional that makes invisible their right to live with dignity.

Sexuality Education would break this deadlock, and the dialogue would change power structures. But we fear this change. As black queer feminist Audre Lorde explains in her ground-breaking essay ‘The Use of the Erotic as Power’, we fear the emotional aspects of sexuality, and we embrace the pornographic for its sensation without emotion, rejecting the sensual. Lorde goes on to tell us how the ‘superficially’ erotic has been encouraged (and used sometimes to emphasize misogynist norms) but deep eroticism is feared. It could be argued that a similar situation exists in India. Women’s and men’s sexualised bodies are superimposed on advertisements everywhere to sell not only commodities but also a certain idea of sexuality. We fear education will topple power structures that can only exist through repression. Perhaps, it is not Sexuality Education, but these media representations that we must fear.