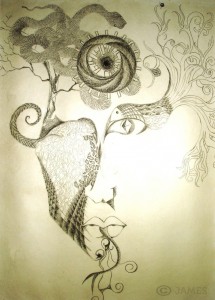

It may be useful to visualize sexual rights as a large tree with deep roots and a vast canopy of leaves. Or as a giant umbrella. Or a big tent. Whatever tickles your imagination and allows you to see it as a conceptual and practical tool to make claims for any aspect that relates to how we express sexuality. It has to do with obvious aspects linked to our sexuality such as the freedom to choose one’s partner, to say yes or no to sex, to decide on whether one wants to have babies or not, to be heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual or however one identifies one’s sexual orientation, to seek sexual pleasure, to have access to information and health services, to not have one’s body violated, etc. All of these are based on underlying human rights principles of autonomy, bodily integrity, liberty, dignity of the person, equality and so on. Nothing new. So why then are sexual rights such a volatile issue and why do they attract so much opposition?

Sexual rights apply to all people, so in that sense they are an equalizer. But as with all rights, mostly it is those people who are being oppressed who will shout loudest for their rights to be respected. So we hear more about LGBTQI people, than about straight people. In most parts of the world, straight people don’t need to claim their right to an identity because a straight identity is bestowed on everyone whether they want it or not! Nor do they need to fight against discrimination at work or on the streets or in the kinds of services they receive. But sexual rights are not restricted to LGBTQI people – they are for all people. They apply also to the straight man or woman who falls in love with someone of another community or religion or nationality, or who does not want to have sex with their spouse. They apply to the woman who does not want to get pregnant or to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term. They apply to the young person who wants accurate information about sexuality. They apply to gender non-conforming people. They apply also to all people who conform to everything society expects them to.

That is why there is so much opposition to sexual rights by religious institutions and people of different faiths and by the upholders of a static, unvarying idea of ‘culture’. What we may see as liberation, is viewed as pure hell by them. What are they afraid of?

Amongst other things, they do not like the idea of women having control over their own bodies and desires, women saying no to sex when men want it,and people marrying across the boundaries of gender, class, religion, caste, race, and all other social ‘barriers’. Why is that so scary? Because to their minds, there is no knowing what the outcome of these alliances may be – not just in terms of kids with ‘mixed blood’, but also in terms of future allegiances like same-sex couples co-habiting, marrying, and so on. If the old barriers are not in place, anything can happen and the powers-that-be will no longer be powerful and able to dictate how people, especially women (remember women are the ‘vessels that transmit culture’), ‘should’ behave.

But it is not just ‘old men with beards’ who oppose sexual rights. It is also ordinary people who misunderstand the meaning of sexual rights. That may be because they equate rights with the freedom to do whatever you want and they imagine that what people want most is to have sex with everyone. And anyway, what’s wrong with that (as long as it is consensual and safer sex being practised)? But that aside, sexual rights are not a license to ride roughshod over other people.

At the very heart of sexual rights is the notion of consent. In fact, sex without consent is a violation of rights. So, unlike what its detractors say, sexual rights is not about people running amok, conjugating with every passing stranger. But you might well ask, if the passing stranger is amenable, then why not? Which brings us to the question of ‘intimacy’. Intimacy is given a high value in certain societies and groups of people. For instance, sex with a stranger is considered ‘worse’ than sex with someone known. In the framework of sexual rights there is no judgment about this. No form of sex is ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than any other. And here lies the subversive potential of sexual rights and perhaps what its opponents fear most – the complete lack of judgment about other people’s sexual desires, aspirations and practices as long as they are engaged in with mutual consent. So they apply equally to the person who seeks sexual pleasure through what others may regard as ‘kinky’ sex as they do to any one else.

When we live in a restricting environment, we may rail against it, but we also become used to battling it all the time. We do not even realize that we are holding ourselves tightly. The potency of sexual rights is that they give us the possibility to dream – to make another world possible. A world in which we can be our true selves without fear, without shame, without apology and without needing to be brave.We are forced to be ‘brave’ to speak out against sexual violence, against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, against a woman’s right to seek an abortion, against a married person’s right to refuse to have sex with their spouse, against so much that violates not only our bodies but also our feelings and our spirit. We don’t want to be brave; we want to be free. And that is a basic human right.

This post was originally published under this month, it is being republished for the anniversary issue.