You’d think art and activism would be chummy pillow mates but they’re often strange bedfellows

Art. Activism. Aesthetics. Politics. This is the problem with words. Sometimes they snake up on you like cobras, twisting, turning, hissing and spitting right back at you.

***

Problem no 1. The word ‘art’ is used too loosely. Is everything art? No. Is every film book poem art? No. It’s a film, book or poem. Is every splotch on a canvas art? No. It may be a good painting without being art, even if it is a painting that has artistic elements. Is every churn of a potter’s wheel art, every twist of clay art? No. Whether the end result is a ceramic vessel for daily use or a giant sculptural figure or a million things in between, only a few of these tiny bowls or tortured giants live on in our consciousness as art.

Poke me with a pin. Let’s see what bubbles up from my sub-conscious as art, without the censors of conscious thought or awareness: TS Eliot’s Four Quartets, Marguerite Duras’ The Malady of Death, Michael Haneke’s Amour, Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grande Bellezza, Jeanette Winterson’s Written On The Body. That’s the first five.

Is this too American, too European, not political enough? No Africans, Asians, Latin Americans, Indians? Not diverse enough? Sorry, can’t tame the sub-conscious.

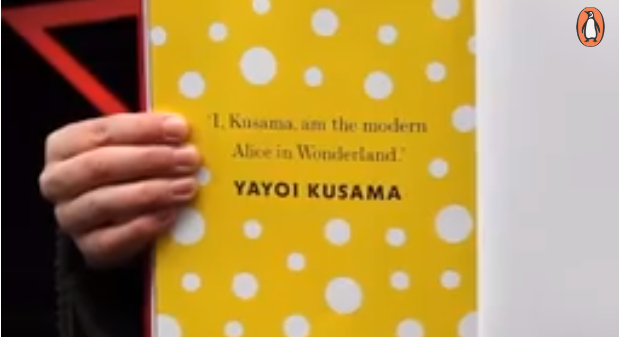

Stroke me with a feather and I’ll open up my mind a bit, let conscious thought creep in a crack. Yayoi Kusama’s artworks for Alice in Wonderland, Sebastiao Salgado’s Workers, Ai WeiWei’s Sunflower Seeds, Malavika Sarukkai’s Bharatnatyam, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s everything.

Is this your notion of art? Maybe, maybe not. But now that we’ve cracked the lid, let’s open Pandora’s box some more.

***

Problem no 2. Who decides what is ‘art’? Who frames what we think of as ‘art’? Largely gallerists, publishers, commissioning editors, reviewers, film juries, artists, big-name backers. Are they able to frame something as ‘art’ because of the positions they find themselves in, their sharper sensibilities, or both? Do they have trained noses like perfumers, able to sniff out what is art? Are they arbiters of ‘art’ because they have the means and power to do so – or the taste to do so? Is something art because it hangs in a hip gallery, is published by a prestigious publisher, wins an award or gets a medal? Because it makes money? What? What if Albert Camus’ The Outsider had never been discovered or published? Would that reduce its ‘art’ quotient or its fame?

You see the problem: everything that gets talked up as ‘art’ is not necessarily art, even though it may have the label.

What is art, and how would we know or define it when we see it? It’s complicated, specially since it depends on everything from institutions to genre histories to constitutive elements to personal taste.

Who should decide what is ‘art’? An important question but can’t go down that rabbit hole right now.

Should art have an end other than being art? Not in my book. To paraphrase Jeanette Winterson in Art Objects, art objects to being freighted with expectations other than achieving its truest form or expression.

***

When I experience something as ‘art’, I mostly do so not because of its theme or its politics, but because of it expression, its combination of formal elements into an aesthetic whole, not because of its activist intentions or nature or its subject matter. Not the what but the how, and the how well. And the how long and lasting an impression this expression leaves on me.

Take the short poem below. I couldn’t care less if these words change the world or not, but I like its cadences. Its craft. Seemingly simple but hard to construct.

‘What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore —

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over —

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?’

— Langston Hughes, A Dream Deferred, 1981

Langston Hughes was a poet and an activist, known for his jazz poetry. Can you tell from reading this poem that he was an African-American leaning towards Communism? I can’t. Did he have politics? Of course; every human being does. Did he bring his politics to his work? Probably. Is this poem activist? Not overtly. Is this poem art? To me, yes. Am I saying that art is an absence of politics or activism? No.

***

All human beings have politics, which some artists bring explicitly to their art, others less so. But it’s always there, be it right in your face or quietly lurking in the background, regardless of whether it can or cannot be seen. ‘I would eat my way into perdition to taste you,’ wrote Winterson in Written On The Body. Could this sentence have been written only by someone of a particular sexual sensibility? (My reflex answer was yes; then I factored in craft and imagination and experience, all of which contribute to creativity, and said no.) Could Frida Kahlo have painted Marxism Will Give Health To The Sick without her political leanings? I don’t know.

That’s the thing with politics; it’s not like a peek-a-boo bra strap, visible on tap.

I think of the relationship between art and activism as one where the relationship between aesthetics and politics is made overt – not just as effect, to the viewer or reader, but as intention, in the mind of the artist. Where an artist – somewhere in his or her consciousness – wants to create change through his or her creation.

A fine intention but one that can sometimes be a spoiler. Specially if Expression feels it must answer to Politics and shuts itself up or adjusts itself to serve the latter. Too often, in activist circles, Politics is the master, Expression its slave. When this relationship is one of master and slave, instead of chummy pillow mates, we end up with tedious films that are like visual slogans, plays without dramatic tension, books full of cardboard characters, dull dialogue, and sentences more suited to academic treatises.

Or Bad Art, Good Politics (although strictly speaking, not art at all).

Good Art, Good Politics? Plenty of examples. I’m thinking Bhajju Shyam’s The London Jungle Book, a collector’s item in which every brushstroke and sentence speaks to his tribal background and his dislocations in the urban jungle of London, but the strokes and sentences reign visually supreme. Or Emma Donoghue’s Room, which captures the experience of a woman in captivity and her son born of rape through an inventive form. ‘Today I’m five,’ are the first words in the book. ‘I was four last night going to sleep in Wardrobe, but when I wake up in Bed in the dark, I’m five, abracadabra.’

Good Art, ‘Bad’ Politics? My favourite is Nabokov’s Lolita, the tale of a 30-something professor’s relationship with a 12-year-old girl. I didn’t find its politics questionable, but put an activist lens on it and it’s a story of child sexual abuse garbed in fine writing. Bad politics. Period.

***

‘Words are sacred,’ said the British playwright, Tom Stoppard. ‘They deserve respect. If you get the right ones, in the right order, you can nudge the world a little.’

Does good politics so often result in poor expression because it doesn’t see sentences as sacred? Because expression is not enough? Because it doesn’t understand craft, that an emerald will only show every hue of green if it is polished to perfection? Because it doesn’t trust in the power of expression to do many things all at once: offer beauty, truth and pleasure, subtly shift emotions, create the distant longings, uncomfortable rumblings or shallow discontents that are precursors to change? Because it freights expression too heavily with content?

‘Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?’

***

Many artists wear their activism on their sleeves – using it a means to express their political passions. I have no problem with that, as long as what they create bears out the Art part of the label, not just the Activist part. Ai Weiwei, Occupy Design, The Guerrilla Girls, the street theatre of Poland’s Carmen Funebre, the intense solo dance work of Marta Carrasco around her alcoholism. Again, just the first five to bubble up.

What I have a problem with is ignorance. Ignorance of the modes, conventions or power of expression. Ignorance that a sledgehammer – or onslaught of expression – does not always hit the nail on the head. Ignorance that a misplaced comma can bring a sentence down. Ignorance of the need to dive into the deep muck, the messiness, contradictions or complexities that manifest themselves in real life and, in say, literature. (When are we going to see a film about domestic violence that gets into the messiness of relationship dynamics instead of skimming the surface?) Ignorance that results in simplistic or sloganistic works, ignorance that measures creative works only on its politics (expression doesn’t matter if the politics is right), ignorance that couples with hierarchy to place cultural expression below politics, almost like its foot soldier, and then beds instrumentality to demand outcomes that are outside expression’s power or scope.

Activists who make art are those who have found their ways outside of this maze, who have found a way to express their politics through their craftmanship, to make their emeralds glow in the dark.

***

…meanwhile my

self etcetera lay quietly

in the deep mud et

cetera

(dreaming,

et

cetera, of

Your smile

eyes knees and of your Etcetera)

-By ee cummings

Video Source: Penguin Books UK