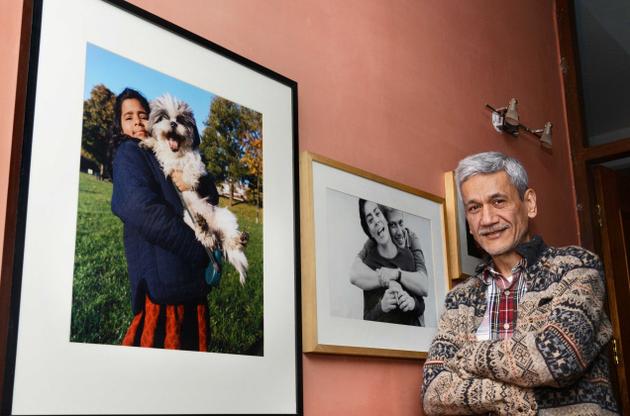

Sunil Gupta is an artist, activist, and a curator, based in London UK. In this interview, he talks to Manak Matiyani about how he has used art as a medium for activism.

For part 1 of this interview, please go here.

Manak: You have spoken earlier about the link between the work of a curator and that of an activist in organizing and connecting with people. You also refer to yourself as a cultural activist, so can you tell me a bit more about that?

Sunil: I referred to myself as a cultural activist, and that comes from a very political moment here in London in the 1980s. When this idea of Black Arts was invented. By that time, I wasn’t an artist in the sense of commercial artists who are involved in making paintings and selling them to the art world, which is just another capitalist venture really. I felt I was involved in not only making the work, but also organizing exhibitions and very importantly, thinking about who the audiences are. Maybe the work should be about the people who are coming to see it. So, I saw my organizing and my chatting as part of the work and my curating was like that.

I curated not by researching art magazines, but by going out to meet people and finding people with sympathetic viewpoints and politics. I didn’t subscribe to this idea that there could be something called ‘good art’. I don’t think art can be quantified or ascribed a certain quality like that. I feel like it either is or it isn’t. My good art is your bad art, and, so what. In fact, the way I went through art school finally, we didn’t have a number system, you either passed, or you failed it. Now that I am teaching a little bit, it is a terrible nightmare because people get numbers, and it’s ridiculous. It’s a bit hard to figure out what’s a 45 and what’s a 55, for pictures.

In Delhi, I was missing a kind of peer group. At a place like Milan, there was this slight unease, because, I was coming from a much wealthier background. Although, I didn’t necessarily think I was rich, but compared to them, I certainly was. I was always trying to explain to them what the pictures were for. There was a lot of media around and they’d love to dress up in a sari, and get filmed or photographed dancing in sari. I was interested in the people as people. I wasn’t interested in them as colorful exotic creatures, which is how they’d like to present themselves. Effeminate or not, the guy was some kind of person in there, so, then I had to explain why I thought that was interesting and worth doing. From their perspective, you took a picture for an event or some celebratory thing.You dressed up for it, put your make up on and then took the picture, not before that. There was a lot of education going on in both directions, and I was trying to figure about what things were like for them, because I never really sat and chatted with people, who were surviving on city streets like that.

Nigah provided this other kind of group that I could relate to and not feel like there’s an impossible divide between us. Aside from the age factor.But at least they were a very articulate bunch of young people, and quite willing to go along with some of experiments that I wanted to do with them.

M: We talk about art being political in general and not being a separate category of political or ‘activist art’ many times;but is activism something different from that?How do you resolve these two in your practice?

S: Officially it seems like it is different, because people explain proper activism is marching on the streets and handcuffing ourselves in front of parliament or rallies or something.What I find interesting and how I have been trained now, is to think of everything as being mediated by culture.So there is no point of your protest if somebody does not document it. The media, and the medium by which it is disseminated is interesting. For me, that medium is visual so I am interested in film and photography.That’s the medium of our times and how most of us get our information.

My problem asa visual artist became that we started with this premise that there is a kind of representation of the politics; the politics being the demonstrations and the confrontations or the meetings.So you photograph or film all of that and make what we used to call, a ‘representation of politics’. You might make a video of a Pride March that says,‘there it is’, showing it in a straightforward way.The art comes when you flip this question and you think about the politics of representation, not just the representation of the politics. By which I mean, you question the politics of the image itself which has many issues embedded in it. It’s not as neutral as we think at first. There are many issues of consent and control. Who took the picture and for whom,stuff like that.

There have been various times in our cultural history, where radical political moves have taken place, shifts let’s say, in the way the image is perceived.Certainly in terms of cinema it’s been like that. And also in terms of photography, what’s appropriate to show and what isn’t and stuff like that.But often I think when a community is feeling very stressed out and under pressure, it prefers to gowith the simpler kind of image.They don’t really want to mess too much with that. So in Delhi, what I experienced by and large was that when it came to representing the politics, the pictures and videos that emerged generally were pretty straightforward. And, we observed that the mass media likes the most drama, so what they liked best was the people dressed up.The place where we could actually experiment and discuss the politics of images was in a gallery. And so when Nigah wanted to do a festival, a couple of us were very keen that we do an exhibition every time because that gave us a way of discussing the image.The politics of the image, not just what was in the content.What interesting ways could we represent lesbian and gay men, or transgender people? During the exhibitions, we had some workshops, which became the site at which the politics got discussed.People would make pictures as a response.I did a workshop with Nigah. We did it every week one summer for a couple of months.To make it simple, we did self-portraits on what everybody thought of themselves. It began in a straight forward way, and then got more and more complicated. At the end I asked, ‘can we do this without clothes?’ To allow everybody see their body as a gay or lesbian body. And all that was quite interesting experimentation.

M: This vantage point of identity has been central to both art and activism in many ways. So in your experience, how did it come into play? And how did it change, like you mentioned that it is contentious.

S: It became very important when I went to formal art school in England and discovered that there was no art history about who I was in terms of identity which was, let’s say, just a gay Indian man.. There was no such creature, there wasn’t a single picture I could find in art history. I became a kind of missionary about it. I decided I would make pictures of gay Indian men, whatever else happened. So I’ve been making that since then and I still am.

Of course the definitions have changed, and when you think of the notion of diversity within India itself, it becomes very complicated. I was in this other country, England, where we were under a Black umbrella, I had to explain to a lot of Indian people here that they were black; they didn’t think so, they thought they were white, or they thought they were Indians or something but they certainly didn’t think they were black. I meant that in a post-colonial way, everyone who had been subjugated by the English Empire at one point.

There was a time in London when Queer actually meant gay men and lesbians having sex with each other. That is what the word ‘queer’actually meant.I never did do that so I just stuck with being a gay man. In Delhi I became aware of a large multiplicity of labels– there was gay, there was lesbian, there was kothi, there was many things happening, not to mention the plain old bisexuals and stuff like that.

Sometimes it can also be quite contentious; I’ve been to some meetings in Delhi, where there have been some very major gender issues. Women have been very irate about gay men and sometime I feel like, you know, there is a scapegoat here for you guys, because women have this longer history of movements and politics in India.For years, there were lesbians in various movements in India, but they didn’t say they were lesbian.They were just from the women’s groups. Whereas, the poor old gay men haven’t been in a movement, they’ve just come for a meeting and the first thing they hear is that they’ve been oppressing everybody. It was never a good way to start a meeting by telling them off.

We have definitions and they are always influx and the meaning of these definitions change and they don’t all change at the same time.In the 80s for example, when I used to come and visit Delhi, I would meet people and they would say, oh I’m gay, and I would say, ‘oh you are not gay, you are married’.To me the two things in the 80s could not reconcile. Being gay meant a political act. You didn’t get married.The first act you did, was to say no to the marriage part. So then, all my peers got married, and I couldn’t and I didn’t believe they were gay anymore. Whereas now when I come to Delhi and people say I am gay, and I have to think, ‘oh yeah, it’s not up to me to decide who they are’, now the fashion is for the individuals to decide what they are, and they might change their mind.

I have had this experience in a way; I might take a picture of you because I think you are a gay man, because you told me so. And in five years time, you might say, ‘arrey, now I am not gay anymore.’ So we have to remove your picture from my collection. That has happened, and in 10 years time, you might decide to be gay again, so who knows?

But now with the whole marriage discussion happening, the interesting thing to recall is that, gay identities came out of a very critical space because they were against marriage and basically against the idea of the accumulation of property, i.e. wealth. There were no children to leave the wealth to, there was no point in creating all this wealth.But we lived in a society where the creation of wealth was a driving force, and I think that’s the heart of the reason why we were successful as a social critique.But now it seems, everybody just wants to be ‘normal’ and get involved in wealth creation and having children and buying houses.The odd thing is, now that they want that, some people in India think that’s unacceptable.Well I thought, they were at the verge of getting the whole thing legalized actually, but in the current situation, we just have to wait and see.

M: With innovation in technologies, people are able to document on their own. And even make images and there is a proliferation of visual material. They are also able to explore identity and their ideas and their body in ways for which we relied on artists. Do you think this is making us, or will make us reimagine how we practice art and activism both?

S:There has been a huge proliferation of images as you are saying, with the help of the internet and technology and the problem with the vast majority of images is that they’re all un-edited. I think we still need some form of editorializing of this material. How that will happen, I am not sure, other than going back to older technologies.It’s a lot easier to upload digital pictures by the hundred than to make paper prints like that. Although there’s a lot more quantity, I find much less of it emotionally moving in a way that I find interesting. At the technical level, the cameras have got very sophisticated to the point that smart phone cameras are very clever now, and technology will take a good picture without the person’s involvement. Which is quite an achievement, it will shoot and take a picture that is perfectly exposed and in focus and everything, but it’s the context and the intention that then becomes more important as to how we see it and what’s framing it. Like, I could do a[Skype]screen grab of you now, and put it somewhere all over the place but it wouldn’t have very much context. But on the other hand if I put it up in London and said it’s a picture of a gay man in Delhi, you know, he’s liable to be arrested and put up in jail for 50 years if you don’t do anything quickly to save him, it becomes whole other issue then. That’s what I mean, the picture needs something around it to make us sort of notice it somewhere.

M: The other aspect I wanted to explore was of addressing themes that are not easily talked about and come with a lot of stigma. Talking about sex and the body and HIV is always difficult. How did you build that, especially talking from a perspective of pleasure and not fear?

S: I suppose I am a product of my time, in the 60s when you came out, it meant it was no longer your problem but the other person’s. And I applied that principle to AIDS when I was diagnosed. I thought I was going to die the next day but I didn’t. Then I thought, okay, the more I tell, the better I will feel, and actually the people around me at first reacted quite melodramatically because now they thought I was going to die very quickly. I had to reassure them, and say I was going to die, but not just now. It is also the combination of coming from the gay liberation movement and the experience of putting work in the public eye as a visual artist.Both taught me that putting something out there is quite liberating.The worst thing you can do is have some kind of secret, a dirty secret you are trying to hide.It creates a pressure on you all of the time, and it’s not necessary.

When you look at the Internet globally you get images of sex, but you don’t get the physical experience of it. And one way in which I like to express it, for example, is actual sex.Pictures of sex don’t convey the quality of what’s happening and my sex life in Delhi was very weird. [laughs] I mean,there was a lot of anxiety in the actual sexual experience. That made it short lived, and it’s anything but a kind of relaxed pleasurable way of having an encounter with somebody else’s body. It was the exact opposite of that. Sometimes people would use poses or language from porn or something. I say this from the global availability of that kind of visual and oral reference but they didn’t know what to do and I began to realize no one is teaching these people what to do.And it doesn’t come naturally. I think for a lot of people maybe privacy is a problem, [and]their own body is problem.There are many issues and I think there is scope in there, for somebody to start a school.Maybe you guys should start a sexual healing course and charge a lot of money.

It would calm everyone down for one thing. In the 80’s when I used to come, there would be a group of people and we would all get together at somebody’s house when the wife wasn’t there or in an office or something. Everyone would get really, really drunk, so for the first three hours, they would just drink themselves silly. When they were properly drunk, there would be this group sex, which used to be awful, because they were too drunk and the environment was terrible. And you may not want to have sex with the person standing next to you anyway, and stuff like that. By then it was a free for all, so it was crazy.

So the internet can’t give you that physical intimacy. That is something in the real world. It can just give you approximation through pictures or something.

M: There is of course the notion of personal being political which has been integral to the feminist movement. There is also the aspect of the intimate, which is central to your work with people. You have worked both in studios where people come to be photographed and by going into people’s houses and their spaces. How did you engage with the personal and the intimate?

S: Some of the pictures, especially the studio ones, I was trying to actually marry a moment in Delhi as I was seeing it to an art historical moment in England where the pre-Raphaelites were trying to radically change their Victorian surroundings.They were young people who were trying tobe more experimental. I literally saw in front of me quite a lot of dramatic changes. And some people I met, I just observed them becoming more comfortable with themselves. Not just very young, early people from Nigah but some more mature people that I came to know.There was something about the late 2000s. There was a growing confidence and people were more happy, or at peace, with their gay or queer identity, or becoming more so. I had a feeling it was having a positive impact on their personal lives, maybe their relationships as well.It’s tricky actually because it’s hard to talk about intimacy and personal relationships when so much of the discussion in politics in India is necessarily focused on broader, more sociological, outside issues, about law and changing the law and so on and so forth. Which is strangely a lot of language that is focused around sodomy.It is about the sex act, but the discussion happens in a very asexual way.Legal matters or feminist issues around gender bending and stuff, anyway, but very little about intimacy.

I think in the [Nigah] festival, the most popular art form was the performance one.People saw it as more immediate and more intimate, because it was a real person saying or doing it in front of you.People really responded to that. I think there was a “high” of seeing more of that, experiencing more of that. I don’t know how many people in India have sex and then talk about it. From my experience, a lot of it was, okay, we might start online, you might have some vague, prelim coffee to make sure the person is not a serial killer or something. [laughs] And then you go on and in 5 minutes it’s over and then they leave and that’s it, no one really spoke about their intimacy. It’s very complicated because then, how do you negotiate your pleasure if you can’t say anything. Would that be political in your eyes?