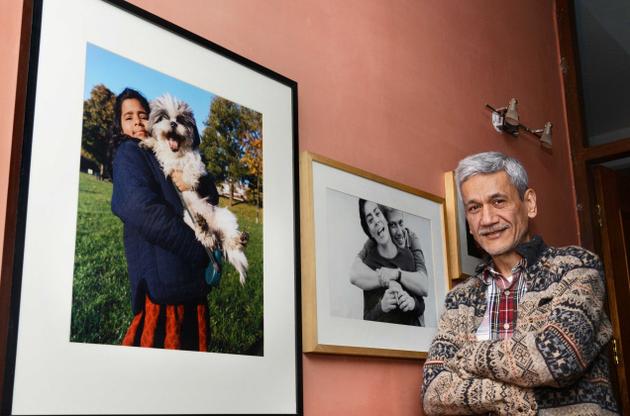

Sunil Gupta is an artist, activist, and a curator, based in London UK. In this interview, he talks to Manak Matiyani about how he has used art as a medium for activism.

Manak Matiyani: You took up the camera as a hobby. Could you tell me a bit about how you started and how it grew into your work as an artist and an activist?

Sunil Gupta: Yes it was a hobby in Delhi. I grew up in the 50s and 60s, and there was a camera at home. I had a friend in school and we set up a rudimentary dark room. It was our joint hobby to make black and white negatives, and process the film and try and make some basic elementary prints.We were doing this without any guidance or access to anything about the culture of photography or actually seeing much photography outside of our own family albums. I carried forward with this interest but right at that point my family migrated. Virtually overnight, I found myself in Canada, in another high school with another bunch of people, and I went to college there.

After that hiatus, I encountered a friend in college and we shared a common interest in cinema. We got together and decided to work with photography as something we could do. He was more of a writer; I was of a techie kind of camera guy. I bought a camera and an enlarger. I used to make prints in my bathroom and he wrote the stories. We were very interested in fiction and in those days Montreal was a relatively small city; I didn’t know it then, for me it was my first experience, and it had a smallish gay scene. It reminds me a bit of Delhi now. The English-speaking world here, it’s relatively small and you see everybody. Even if you don’t speak to them, you know them visually. To eliminate the boredom, we created some fictional characters. We gave people fictional identities and names and histories, and created a kind of soap opera if you like. We referred to them by their fake names in the bar. So that’s how it started, very much out of a gay experience.In retrospect, I can say it was driven by an experience of being young and gay and coming out at more or less that time in high school and college. I wanted to say something about our time and that’s really how it came about.

A little bit after that the politics started as well. I arrived in 1969, a month after Stonewall, and by 1972, we had gay politics in our local areas. In my student years, we had an active undergraduate gay group in the university. We had a little newsletter that I made the pictures for. So, that was my first published work in a sense. It had a little local audience. The stories were about the local scene and the local politics. I would cover demonstrations and go photographing the gay venues. Sometimes there would be real ‘news’. A gay bathhouse caught fire one day with some people inside and I went to photograph the aftermath. So for me, the photography kind of became more entrenched with the gay experience as it was happening.

The other thing that happened to me at that time was a weird kind of identity issue. I was 15 when I was moved from India by my parents. Without thinking much about it, I went from being what I thought, was an ordinary middle class Delhi person,into this other place in Canada where nobody had a clue about that. I found that my preceding 15 years were worthless. It was a difficult first year in high school where none of my peers had any idea about where India was on the map. It was the 60’s and there weren’t many [Indians] around then. And North American kids didn’t get exposed to a lot. I had to ditch any Indian aspect [of my identity] because it didn’t make any sense.What did make sense was this emerging gay identity which was much more powerful. The Indian thing only worked at home with my parents. It was very limiting and it was just inside the home.

In school, it was cool to be gay, it wasn’t cool to be Indian, let’s put it that way. I earned more currency out of it. Nobody knew what an Indian was actually. It was the end of the 60s and ‘gay’ had a certain alternative, counter-cultural flavour to it.

M: You mentioned that there was a gay politics emerging at that time.How did you begin to get involved with that?

SG: One part of it was the activism.The college group then decided to move out of college and become more of a city group.There was a bit of tension at first, because the university group was focused in a certain academic kind of way, and people who came from outside the university were just regular people. They had a different vocabulary and talked about things differently. There were demonstrations and activities planned and different kinds of sub-groups. Support groups for example, like telephone helplines and that kind of thing, and I joined some of those. The public demonstrations became something I felt I should document. So, I used to go around and photograph. In a way, the activism provided the activity that needed to be photographed.

MM: And at that time, was it a thought out, conscious choice to approach it as a photographer, or was it more impulsive?

SG: I found it a great help to try to figure out things with the help of a camera. It gave me a certain distance from the reality of a situation. Being behind the lens gives a certain critical distance. I could approach people through it. I might have been more shy and it became a tool just to approach people and to sometimes just chat with them.

In a big crowd of gay people, having a camera, taking pictures can generate more discussions. Otherwise, the only other possible discussion was, ‘Do you want to sleep with me?’ This gave me another way to interact with other gay people. I preferred to shoot them, because it had the element of meeting other gay people, especially once we left the university setting and became a part of a wider pool. It wasn’t just students anymore and people were harder to meet. But this was a part-time activity of course. I was a full-time student and I was studying something quite different. So in my academic world, there was no room for this. I was in a business school, I had a degree in accounting; I was studying accounting, so there was nothing queer about that.

MM: Yes, your academic training was not in photography or art or even the social sciences. That actually happened more informally. So how did you shift from accounting to art and activism?

SG: That happened more self-consciously some time later. In between, I had this period of transition for about a year in New York. I went to study for an MBA, you know, business studies. But I was also away from home, living in a different city from my parents for the first time. New York for me was a big eye-opener. With less than 2 million people, Montreal is a very small place compared to New York. Cultural stuff came to Montreal but little got made there. What got made was in French so I wasn’t accessing that. I, being English speaking, felt that everything came from Hollywood or New York or somewhere else bigger and was not made locally. So I had no idea or aspiration to make anything because I knew there was no way I could produce it there. In New York, suddenly I found a place where things got made. I had a feeling there were a large number of people, in the streets, around me, who were all trying to do something other than just make a living. They made a living anyway they could, but they were trying to be writers, or actors or artists of some kind. It was the first time I encountered that possibility. I had a very rigid Indian middle-class upbringing where you just went to school and you studied business or engineering or medicine and you got a job and you were straight and there was no room for anything else. So I was very inspired by this, and also, I was very fortunate to be with somebody who had a job and who could support me. He encouraged me to take up photography, we discussed it and I took a risk. I dropped out of the MBA program informally and just stopped going to classes. I enrolled in some photography classes, at another institution. At the end of that year I was discovered by my parents. They got a bill and this transcript saying I didn’t attend any classes so I had to go back to Canada and deal with it. But by then, I had transitioned into photography.

In New York in the mid 70s, there was a big explosion of photography galleries. Suddenly there were more than 50 individual photo galleries. I was quite amazed by the sheer extent of visible cultural production. I didn’t even realize that there were photographs in a frame in a gallery that existed or that it was happening at such a scale. I very quickly began to realize that something big was happening in photography, there was an art market for it. It was collected by museums and they were showing it. And I became aware of things like auctions and auction houses that were selling photography. I became aware of the whole business of art and photography. And I became aware of the museum history of photography by just going and studying it on my own.You can do this in western museums as all these histories are up on the walls. The place in New York that had most of it at the time was the Museum of Modern Art which told this very Modernist history, which I accepted without too much criticism.

So, in the mid-70s I got this kind of informal education, slightly formal in the sense that I attended some workshops with well-known practitioners of the time.They encouraged me to carry on with photography even though I had a premonition that it wasn’t going to make me any money. I had this very Indian idea of thinking, ‘So what’s the job?’ And there is no job that you do.There is no job at the end of it. I left New York thinking that if I wanted to do classic, mid-twentieth century kind of photography which is black and white, negative-positive, dark room, silver printing, like a craft, you know, to make very nice prints, that people might appreciate it. This was aside from the content. The content I was pretty sure about was something gay related. But it had now opened up, because of my exposure to modernist photography.

There was also a lot of hanging out on the street with the camera. And New York was an interesting metropolis. It’s kind of like Bombay. It presents you with very different neighbourhoods, you stand on one street, you get one kind of person, and you go somewhere else, you get a different kind of person. It can change at different times of the day, and so on. And street photography had appeared in the museum so I knew it was a valid way of working. There was that kind of formalist training or exposure I got, and it wasn’t until a bit later when again by chance, the two of us moved from New York to England that I went to Art School in England and things started becoming more political again. New York wasn’t really political in that sense. I didn’t become part of any groups or anything. There wasn’t much activism.What there was, was actually a very public gay culture that I tried to become a part of. This was centred around Christopher Street, which had hundreds of out gay men on the streets every day. It was something I had never seen before, and maybe I fantasised about this in my activist days. This was going to be the result, anyway, it certainly seemed like it.This was New York before AIDS. There used to be that saying about, ‘too many men, too little time’. That’s how it felt like, everywhere you looked, there were gay men, and not only gay men, but good-looking gay men who wanted to have sex all the time.You kind of forgot the activism for a while. [Laughs]

MM: When you came to Delhi in the early 2000s for a show you got involved with Nigah which was a nascent queer collective at the time.

SG: I had a show in 2004 in the India Habitat Centre that had 4 bodies of work that talked about my being gay and my being HIV positive. And I wasn’t sure how an audience in Delhi would see that,but Radhika Singh, the person who organised it said Delhi was kind of ready for it. She organised it and did the ground work. We put it up and showed the works without any hassle. There was just one full-frontal [nude]picture that the Habitat people thought we shouldn’t have because kids come and see the exhibitions.So we took it down and the rest seemed okay. I got quite an incredible response. All kinds of people came. I think some because of the pictures and some otherwise. I felt a lot of people came to stare at me because I think I advertised that I was HIV positive. So someone would work up the courage to come and sit beside me and ask me some questions about being gay and HIV positive. It was quite a good turnout and we expanded the show because there was a space available in the room next to the gallery. Radhika in her wisdom had organised two kinds of film programs. One was about AIDS and NGO activism; actually, quite boring government movies about HIV awareness. We had that, and we had a more exciting program, which she had asked Nigah to do. She had somehow found them. So, that’s how I met them, they had organised a film programme. And, in between the two spaces, we used to have cups of tea and samosas on the terrace. During my show, for 10 days, this became like a gay scene.In the middle of the day, people would come and there was tea and samosas, and homosexuals hanging around. I didn’t realise it was some kind of novelty, so lots of people came. And then in the process, I encountered somebody and it provoked me to move to Delhi. Most of my big country moves have been made for the wrong reasons.[Laughs]

MM: I believe you moved twice to be with somebody.

SG: Yes, but by the time I moved, the person was no longer interested, so I was in Delhi without somebody. But I had made such a drama about going to Delhi that I couldn’t do a U-turn suddenly. So, I thought I’d better stick it up. I was very attracted to working in Delhi because it’s full of narrative stories and histories, and that appealed to me.The many layers and levels of history in Delhi. I started to feel like it’s like a home town for me because I was born there and it was very familiar. The only problem I had in relation with living in India was that being gay would be terribly traumatic. Before this experience, I used to find the whole gay thing was too weirdly never talked about with anybody. But this time I found, the things had changed quite a lot. There were already some groups happening. There were some AIDS funded groups happening, and there had been a kind of gay men’s group that had happened. So, generally there seemed to be more activism around, some of it had come and gone, but certainly had left some kind of impact.

My primary reason for being in Delhi was to get involved in some kind of photography. My friend Radhika Singh had organized that show and she was a great help in trying to set me up. I got a job from London to research Indian Photography and that kept me going for a couple of years as an activity. It led me to work with some local Indian galleries and we realised that there was very little published research on Indian photography. So we had to do a lot of primary research and that led to some shows that I was doing.

I started to think about making my own work and in the meanwhile, I tried to visit some of my immediate, available gay groups that I could think of. In those days, most of them worked through the HIV funded networks. So first I tried to go to the Delhi branch of the HIV funded groups. I found that actually it was a health group for under-privileged people. For infected people who were also very badly off economically and it was all about trying to help them. I was kind of an odd person there. I shared the virus but I didn’t share the economic status. I realized, it wouldn’t be a good place to try and do something, because really, what people there needed was money. I really couldn’t do it personally and if I spoke to anybody, it would generate this unequal economic situation where I feel like, ‘now, I’ve got to help them’. There was also a men’s group that was started out of Naz. It was called Milan, and it was in Lajpat Nagar. I used to go and hang out there for a while, and try and meet people. In retrospect I realize it was very typical. It only got going in the afternoon, and lot of Kothis used it. They would actually do their makeup and dressing there and then go out into the streets with safe sex messages and condoms. So while they were there for couple of hours, between 4 and say 6:30, there would be a crowd of people that would mingle with them and chat. It was quite interesting and had a very particular AIDS focus, which suited me up to a point because I was HIV positive myself. That gave us something to discuss, treatment issues and stuff like that but then again, there was this whole economic issue. That’s one thing I had forgotten about not having lived in India for a long time. That the way it is divided so much by money more than anything else. I started there, and I did some photography and some video.

Meanwhile I met the other people from Nigah. They persuaded me to join them although I said I was way too old because they were in college then and I think I was older than their parents. But they reassured me that it would be okay.

[Watch this space for Part 2 of the Interview later in the month]

Pic Source: The Hindu

Interview transcribed by Ankit Gupta