My love affair with cricket began exactly twenty years ago. It was an impulsive decision based on an instinctive urge to be more of a ‘son’ to my father. The world that we lived in defined my father as a successful businessman who had found himself in an unfortunate circumstance – he had only two children, and both were daughters. My sister and I were keenly aware of this ‘problem’ from a very young age, mostly because these noble representatives of society were never shy of mentioning this ‘problem’ to my father in front of his two little girls.

I was about eleven years old at the time, when one afternoon, as Father sat in front of the television screen, engrossed in a game of cricket, I approached him with the clear purpose of solving the mystery of this sport. All I knew until then was that there are eleven players in each team, and the game involves a bat and a ball.He patiently explained the rules while his eyes stayed glued to the screen. Over the next few days, as the mystery of cricket began to unravel in my eleven-year-old mind, the original intention of trying to be a ‘son’ to my father began to dissolve. I was smitten. The dream: One day I shall play for the Indian men’s cricket team.

The dream soon turned into an obsession, fuelled by my kind and supportive father who would’ve done the same for me no matter what I had decided to obsess over. Before I knew it, my whole life revolved around cricket. I had a room full of posters of men who played cricket, and a brain full of cricket facts and trivia. The posters covered every inch of my room. I remember picking up new ones every other week from the street-side sellers of Connaught Place in Delhi, and found one with every new issue of The Hindu’s sports magazine called Sports Star.

I watched every game with equal enthusiasm, be it a one-day match, day-night match, or even test cricket.With the short format and even shorter format commercial cricket tournaments that we see today, it is hard to imagine an 11-year-old with the patience to religiously follow each ball in a five-day-long test match.To me, it didn’t make a difference if the games were played in my part of the world or in the Caribbean or in Australia. Through cricket, I learnt about global time zones and how to balance school and homework with matches that happened through the night, or those that started before dawn.

The learning and the watching led me to playing. I carried a cricket bat to school, much like a lot of boys in my class. All the other girls would be happy running around aimlessly or playing games. They looked at me as if I had lost my mind. And the boys couldn’t be bothered with playing cricket with a girl. I eventually decided to leave the bat at home.

If no one at school was willing to play with me, I had to think of something else. By this time, I had read a lot about Sachin Tendulkar’s growing-up years, and how he practised his batting at home with a ball hanging from the ceiling. I decided to learn from the master and followed in his footsteps. Every afternoon I could be found alone in our balcony, hitting the ball over and over with my cricket bat.

Watching my continued attempts at learning to play, my dad offered to take all of us out for a game of cricket. We packed our gear, which by now included wickets, gloves, batting pads and a red leather ball, and landed up in the lawns of India Gate for a game of family cricket. Within minutes, the fun came to an end. The hard leather ball had hit my father on his wrist, and he was in a lot of pain. We sheepishly packed our gear and took off for the hospital, never to return to India Gate with a cricket bat in hand.

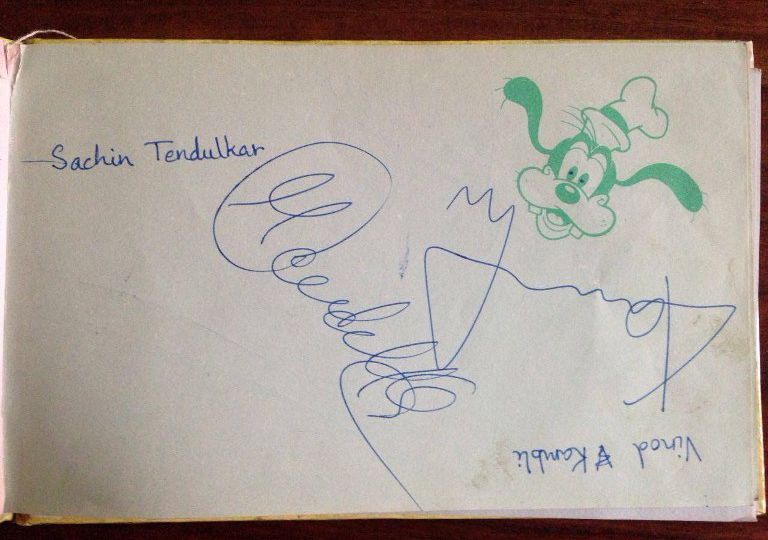

If not in the field, my father made sure I got a good dose of my favourite cricketers. Every time the Indian team was to go for an international tour, they always flew out of Delhi. And every time they were in Delhi, they stayed at a particular 5-star hotel. My father knew this because he was now a father of a cricket-crazy child. Every time the team was in town, we went to have dinner there.When I think of those evenings now,with my sister, a male cousin and I running around the hotel lobby with our cameras and autograph diaries in tow, I can say with confidence that mine was a family of well-meaning stalkers.

I still don’t know how we managed to get there at the exact time the players were out and about, having dinner, all dressed up in their navy blue national blazers, posing for the press and obliging fans. But for a teenager, the feeling of seeing her heroes up close, getting to stand next to them and pose for photographs, getting their signatures in her diary, can be truly magical. On one such night, just as we pulled into the hotel porch, the whole team was assembled on the staircase in their Sunday best. I clearly remember my heart pounding in my chest while looking at this most beautiful spectacle.

While cricket becoming a part of our daily lives was absolutely normal in a cricket-crazed nation like ours, the chances of a 13-year old girl playing for the Indian national men’s team clearly wasn’t. I still wonder how optimistic I must have been to harbour such a dream; to even imagine that such a thing would ever be possible – a mixed-gender national cricket team in a country where mixed gender teams are unheard of, in a world where social acceptance of mixed gender sports teams is sorely lacking.

At some point, the optimism wore out and I began to see myself through the eyes of those around me who accepted the status quo as the only possible reality. I realised that mine was an impossible dream, and I felt foolish to have dreamt it in the first place.

Soon after this first jolt came another even bigger one. I was 14 years old in 1999 when my world came crashing down and my love for cricket came to an abrupt end. The sport that I had loved and worshipped day and night for years together became tarnished with match-fixing and betting scandals. My innocent fascination with the sport and blind belief in the players and their abilities had been completely destroyed. It felt like a personal betrayal by players who I had thought of as noble, virtuous actors in the sacred field of cricket. I felt like a jilted lover. Posters came off and the passion disappeared. The hurt that I felt was in a way a coming-of-age for me.

Given a chance to go back and do things differently though, I would not change a thing.But I do wish I knew back then that no dream is too bizarre or unachievable; all one has to do is find ways to sustain it within themselves. I wish I had known that the possibilities are unlimited, and the world is out there waiting for me to shape and create it the way = I would like. Even if mixed gender teams did not exist at the time, it did not mean that they never would. I wish I had known this back then.

Cricket may not be all that I made it out to be when I was a teenager, but it taught me some valuable life lessons.I know now what it feels like to be passionate to the level of madness, to be loyal and to be honest. I know the freedom you feel when you fall in love with absolute faith. I know the beauty of believing in someone with child-like innocence. I know how a fantasy can become a dream and then a reality if you really stick with it.

Cover illustration by the author