When working with parents on child sexual abuse (CSA) prevention, I often get asked the question, “How old should my kids be before I talk to them about sexual abuse?” My usual response is, “How old do kids need to be before they can be sexually abused?” The truth is that no age is too young for a child to be sexually abused. Surprising though it may sound, all children, including babies, are vulnerable to abuse.

Preventing CSA isn’t children’s responsibility. Since violence against children is primarily perpetrated by adults,[1] it is adults’ responsibility to end it. That said, parents and other significant adults can help children participate in their own protection. One way of doing this is by talking to young children about emotions and feelings, letting them know that their bodies belong to just them, helping them recognise unsafe situations, and teaching them skills to deal with such situations such as by saying “no”, getting away, and telling someone.

While CSA prevention education is important and helpful for children and adolescents, it can be somewhat limited in its utility and efficacy. Children may be too young to comprehend and/or articulate prevention rules and ideas. Also, most perpetrators are known to the children they abuse. They may be the child’s teacher, uncle, sports coach, father, neighbour, doctor, grandparent, or someone else with power over the child. When confronted with the circumstance of being molested by an authority figure, it isn’t easy for kids to protest or disclose.

For CSA prevention education to be optimally impactful, it has to accompany sexuality education. Sexuality education is not narrowly restricted to ‘how to have sex’; it is a broad concept that includes information on respectful relationships, consent, sexual health, safer practices, contraception, sexual orientation, gender norms, body image, sexual violence, etc. Therefore, the term ‘comprehensive sexuality education’, admittedly a bit cumbersome to use in common parlance, is a better descriptor for the kind of sexuality education I am referring to.

Sexuality education is meaningful for children of all ages. Sexuality is intrinsic to human life and experience; all people are individuals with sexuality, and children are no exception. There is no magic age at which we suddenly acquire sexuality. It isn’t externally bestowed, rather it’s innately present. This doesn’t mean, however, that all people experience and express sexuality in the same manner. A young child is going to experience sexuality quite differently from a teenager approaching adulthood whose experiences of sexuality, in turn, are likely to be markedly different from an older person.

Two 26-year-old romantic partners discussing which method of contraception is best for them are engaging with sexuality, as are two 6-year-old friends playing ‘doctor-doctor’ and being curious about each other’s bodies, although their understanding and articulation of sexuality is bound to be different. Sexuality education, therefore, has to be age-appropriate and context-sensitive[2].

Commonly, sexuality education is associated with schooling. While it’s true that many schools provide sexuality education to their students, it needn’t – in fact, it mustn’t – stay confined within the domain of formal schooling. SIECUS[3] defines sexuality education as a “lifelong process of acquiring information and forming attitudes, beliefs, and values”. There is no set age or specific place to receive and process this information, and parents and families have as much a role to play as teachers and schools.

*

Here are some reasons why comprehensive sexuality education has distinct benefits for preventing and addressing CSA in the following ways:

- Sexuality education helps children learn important vocabulary

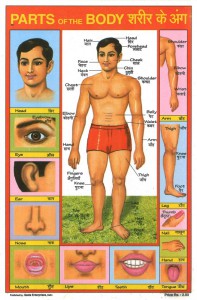

Remember the ‘parts of the body’ poster that used to be a regular feature on the walls of elementary school classrooms? It carried an illustration of the human body, naming many of its parts, and nearly always depicted a light-complexioned non-disabled male.

This boy/man would always be shown wearing underwear. So while his heels, hands, chin and shin were clearly labelled, the sexual and reproductive organs were censored out by the underwear. Similarly, when parents teach young kids names of different body parts, they often skip the genitals. If at all kids learn any names for these from their parents, these are awkward ‘code words’ that implicitly carry the notion of non-propriety.

Since in a male-dominant society boys enjoy a greater degree of permissiveness to talk about sex, they will usually learn other names to refer to the genitals but these words are often also used as ‘cuss words’ and therefore considered uncivil.

When children experience sexual abuse, they face challenges in disclosing it because either they lack the vocabulary for referring to their genitals, or the names they know are associated with shame. It is important that children learn the anatomical names of their sexual and reproductive organs – penis, vulva/vagina, anus, and breasts – and sexuality education helps children learn this vocabulary.

- Sexuality education helps destigmatise sexuality

Shame and stigma vis-à-vis sex and sexuality keep CSA hidden. Children learn at a young age that certain zones of their body are associated with shame. They often get scolded or punished for touching or mentioning their genitals. Young girls learn that society denies their sexuality, even as it stays obsessed with sexually objectifying girls and women. When we perpetuate silence and stigma around sexuality, we empower sexual abuse perpetrators by making it difficult for children to talk about their abuse experiences. Sexuality education challenges this by acknowledging sexuality as an integral and natural part of life.

- Sexuality education questions gender norms

Gender norms are restrictive largely for girls and women, but also for boys and men, and have far-reaching consequences leading to gender-based oppression. CSA is rooted in patriarchy, and gender norms are one of its defining features. Male entitlement, sexual objectification of girls and women, minimisation of sexual violence, treating men and boys’ sexual harassment of women and girls as ‘boys being boys’, and suppression of women and girls’ sexual autonomy are components of patriarchy that often manifest as gender norms, and support CSA and other forms of sexual violence. Sexuality education helps children and adolescents question gender norms through understanding that these are socially constructed and discriminatory.

- Sexuality education addresses body image issues

High self-esteem is a protective factor against child abuse. Among adolescents, particularly girls, low levels of satisfaction with one’s body can damage self-esteem. Good peer relationships are another protective factor. When adolescents get ridiculed by their peers for the way they look, it leads to social isolation and makes it difficult for them to build healthy peer relationships. Sexuality education addresses body image issues and challenges sociocultural norms that put pressure on young girls and boys to aspire for a certain body type.

- Sexuality education confronts homophobia

Homophobia silences survivors, particularly men and boys. Most CSA perpetrators are men, including when boys are victims. Boy survivors may feel anxious or confused about their sexual orientation because of pervasive homophobia. They may feel apprehensive that others will perceive them as gay, and fearing stigma, may not disclose their abuse experiences. People may disbelieve or minimise survivors’ experiences because they perceive these as ‘gay experiences’, and assign shame or blame based on homophobic attitudes instead of offering empathy and support. The assumption that sexual abuse determines sexual orientation is neither scientific nor helpful. Sexuality education encourages young people to think critically about sexual orientations, and challenges the notion that heterosexuality is the only ‘normal’ or ‘right’ sexual orientation.

- Sexuality education challenges victim-blaming

Victim-blaming empowers perpetrators and disempowers survivors of CSA. Children and adolescents may be blamed for agreeing to or participating in their own abuse, or for not disclosing immediately. Girls in particular may get blamed for wearing ‘revealing’ clothes or behaving in a sexualised manner and thereby ‘attracting’ the abuser’s attention. These are just some examples of victim-blaming that frequently occurs within families, peer groups, the criminal justice system, healthcare system, etc. Such practices minimise, if not absolve, perpetrators’ responsibility.

Sexuality education counters victim-blaming by putting consent front and centre; it emphasises that sexual activity is not okay when a person does not or cannot give informed and full consent, and violence in sexual relationships is never acceptable. When young people learn about consent and violence in the context of sex and sexuality, they also learn that people who didn’t or couldn’t consent, and those subjected to violence, should never be blamed for their victimisation.

*

Most parents care deeply for their children’s safety, which is why there is an increasing openness and acceptance among parents regarding CSA prevention programs in schools, although many still feel personally inhibited to broach this subject with their children. However, they aren’t usually as receptive toward sexuality education. They may think that sexuality education is an unnecessary distraction from academic learning and/or promotes reckless sexual activity. Such beliefs, however, are neither supportive of children and young people’s rights nor based on evidence.

Sexuality education, provided at school and at home, can help parents in protecting their children against CSA. Not all models of sexuality education are alike and they vary in their ability or willingness to cover the points mentioned above. However, comprehensive sexuality education should encompass these points, and parents should ask for these to be included in sexuality education curricula. There are many good reasons for facilitating children and young people’s access to comprehensive sexuality education; preventing and addressing child sexual abuse is certainly one of them.

[1] Most CSA perpetrators are adults, although children and adolescents also sometimes sexually abuse other children or adolescents.

[2] Check out TARSHI’s age-appropriate, context-sensitive sexuality education books – The Red Book for 10- to 14-year-olds, The Blue Book for those who are 15 or older, The Yellow Book for parents, and The Orange Book for teachers.

[3] SIECUS (Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States) is a non-profit organisation that develops and disseminates information on comprehensive sexuality education.

Cover image from International Women’s Health Coalition

This post was originally published under this month, it is being republished for the anniversary issue.